The Case of the Fiddle Playing Fox (2 page)

Read The Case of the Fiddle Playing Fox Online

Authors: John R. Erickson

Tags: #cowdog, #Hank the Cowdog, #John R. Erickson, #John Erickson, #ranching, #Texas, #dog, #adventure, #mystery, #Hank, #Drover, #Pete, #Sally May

Chapter Two: Little Alfred's School of Cat Roping

I

looked at Drover. “What did he just say?”

The question caught him in the middle of a yawn. “What? Who?”

“That rooster. He just said something over his shoulder.”

“I didn't know chickens had shoulders.”

“Over his wing!”

“Oh. Yeah, I think he did say somethingâabout a gigantic fiddleback spider in the night.”

“Hmmm. That's funny.” Suddenly Drover began laughing. I stared at him. “What's so funny?”

“I don't know, but you said it was funny and all at once I thought it was funny, too, and I guess . . . well, I couldn't help laughing.”

I narrowed my eyes and studied the wasteland of his face. “Are you trying to make a mockery of my investigation?”

“No, I just . . . couldn't help . . . laughing . . . is all.”

“Well, this is no laughing matter, so wipe that stupid grin off your face.” He wiped it off.

“That's better. Now, let's start all over again. What did J. T. Cluck say? It was something about a fiddle.”

Drover rolled his eyes and chewed his lip. “Fiddle. Fiddle? Fiddle. I'll be derned, I just drew a blank.”

“You drew a blank the day you were born, Drover, and it settled between your ears. ConcenÂtrate and try to remember. Fiddle.”

“Fiddle. Oh yeah. He said he woke up in the night and saw a gigantic fiddleback spider crawling into the chicken house. I think that's what he said.”

“That's NOT what he said.”

“I didn't think it was.”

“He said he heard Mysterious Fiddle Music in the Night.”

“Oh yeah, and the spider was playing the fiddle behind his back.”

“He said nothing about a spider.”

“I didn't think he did.”

“So we can forget about the spiders.”

“Oh good.”

“But we can't forget about the Mysterious Music.”

“No, it kind of gets in your head.”

“Which means that we have an unconfounded report from an unreliable source about Mysterious Fiddle Music in the Night. Hence, the next question is, do we dismiss it as hearsay and gossip, or do we follow it up with a thorough investigation?”

“That's a tough one.”

“And the answer to that question, Drover, is very simple.”

“That's what I meant.”

“We follow it up with a complete and thorough investigation, because to do otherwise would be a dare election of duty.”

“I'll vote for that.”

I began pacing. As I might have noted before in another context, my mind seems to work better when I pace.

“Question, Drover. Do you know anything about this so-called Mysterious Fiddle Music in the Night?”

He flopped down and started scratching his left ear. “Well, let's see here. Fiddle music. I always kind of liked fiddle music, myself.”

“Yes? Go on.”

“Especially when they play fast. It gets me all stirred up.”

“Get to the point.”

“The point. Okay, let's see here.” All at once his eyes got big and his mouth dropped open. “Say, you know what? I dreamed about fiddle music last night!”

I whirled around and paced over to a point directly in front of him. “All right, very good, we're getting to the core of the heart. You say that you dreamed about fiddle music last night?”

“Yeah, I sure . . . unless . . . gosh, maybe I didn't dream it. Maybe . . . there was this fox, came out of nowhere and stood over me while I was asleep. And Hank, he was playing a fiddle!”

I let the air hiss out of my lungs and my eyelids sank. “Okay, never mind, I'm sorry I asked, I should have known better.”

“Did I say something wrong?”

I refilled my lungs and raised my lids. “I thought we were on the trail of something, Drover, but it's turned out to be another of your wild, improbable fantasies. Number one, there are no foxes on this ranch.”

“Oh dern.”

“Number two, even if there were a fox on this ranch, which there isn't, he wouldn't be playing a fiddle because foxes don't play fiddles.”

“Huh. Maybe it was a harmonica.”

“Number three, you're wasting my valuable time. I don't want to hear anymore about foxes or fiddles or spiders.”

“But Hank . . .”

“Period. End of discussion. Now, what were we doing before that rooster intruded into our lives and got us stirred up about nothing?”

“Sleeping, I think.”

“Wrong again, Drover. YOU were sleeping. I had been up since before daylight, checking things out and getting the day started. Speaking of which, the day has started and we have two weeks of work to do before dark.”

Just then I heard the screen door slam up at the house. Hmm. Oftentimes the slamming of the screen door at that hour of the morning indicates that Sally May has come outside to distribute juicy morsels of food left over from breakfast.

“Come on, Drover. Never mind the work, it's scrap time! To the yard gate, on the double.”

We went streaking up the hill, just in time to see Pete the Barncat scampering towards the yard gate. No doubt he too had heard the screen door slam, and he, being your typical ne'er-do-well, freeloading, never-sweat variety of cat, had been lurking in the flowerbeds, waiting for someone to come out and give him a free meal.

That's one trait in cats that has always burned me up. You'd think that a ranch cat, a barn cat, would feel some obligation to get out and hustle and earn his keep.

Not this one. He spent his entire life lurking around doors, and the instant he heard someone coming out, ZOOM! There he was, rubbing up against someone's leg and purring like a little motorboat and waiting for a handout.

It's disgusting, is what it is, and the worst part about it is that his handouts cut into our Food Rewards for Meritorious Service.

Don't let anyone kid you. There's a huge difference between mere handouts and Food Rewards, but never mind the difference because the sleen-scrammingâscreen-slamming, that is, turned out to be a false alarm anyway. For you see, the person or persons who had emerged from the house turned out to be Little Alfred, not Sally May as you might have suspected, which meant no scraps.

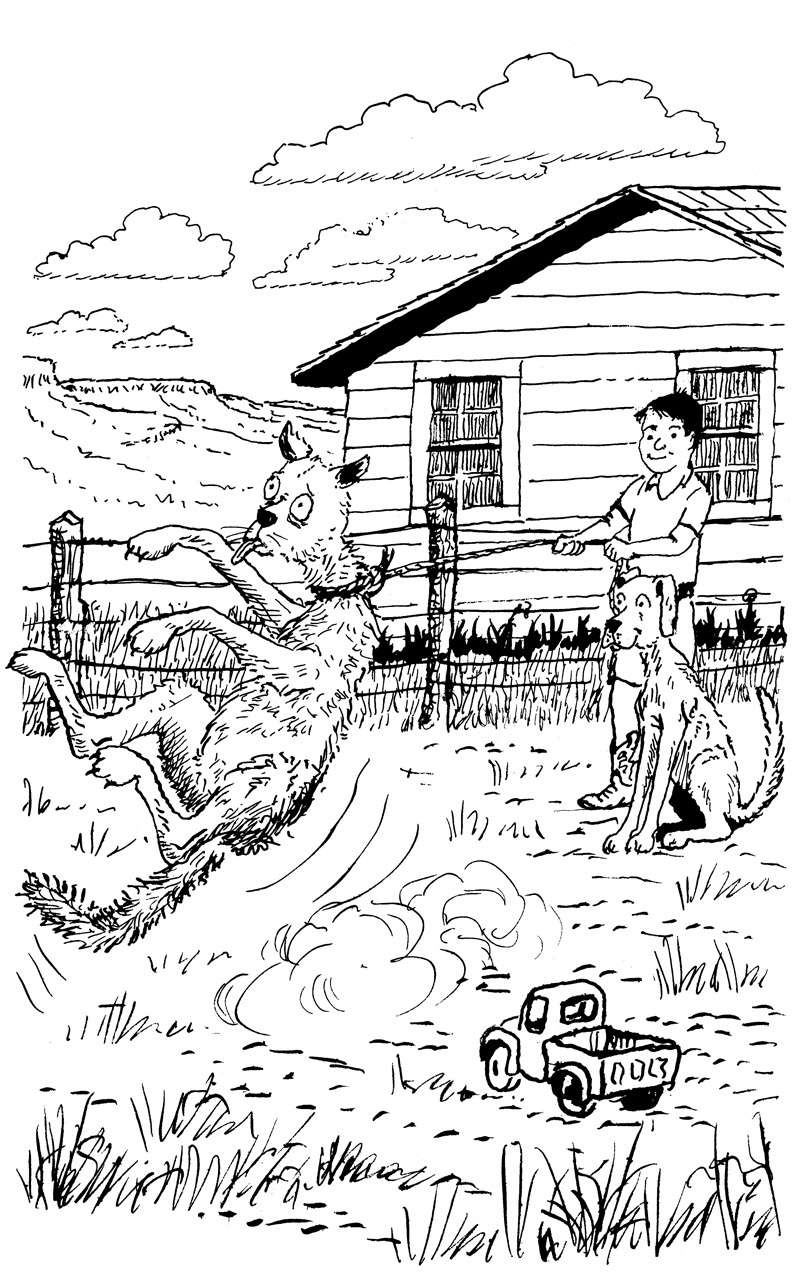

We skidded to a stop in front of the yard gate and waited for our pal, age four or thereabouts, to come out of the yard. He was wearing a pair of brown shorts, a T-shirt, and his little Tony Lama boots, with the spurs attached.

And in his hands was an instrument of mischief: a little three-sixteenth-inch nylon rope. And he was building a loop.

It's amazing what happens to Drover when someone shows a rope. He suddenly changes direction, drops his head, and begins slinking away.

Sure, he'd been roped a few times by cowboy pranksters and he didn't enjoy it, but so what? That was no reason for him to be a spoilsport and a chicken-liver about it. Shucks, if I'd had a bone for every time I'd been roped by Slim and Loper, I'd have been one of the 10 wealthiest dogs in the country.

But you didn't see me slinking away every time somebody showed up with a rope in his hands, and besides, I had reason to suspect that Little Alfred couldn't hit a bull in the behind with a bass fiddle, much less toss his loop around my neck.

Furthermore, there was always the chance that he might put on a little exhibition, with Pete playing the part of livestock. Stranger things had happened, and I didn't want to miss a minute of it.

I mean, if you care about cowboying, you like to see these kids learning to rope and carrying on the skills into another generation, and when they're roping cats, it warms the heart even more.

Pete suspected nothing. That wasn't exactly the biggest surprise of the year since cats aren't what you'd call cowboy animals. They don't understand the business at all and have no idea of what goes on inside a cowboy's head.

We cowdogs, on the other hand, have a pretty good reading of a cowboy's mind, and one of the first principles we learn is that

a loaded rope tends to go off

.

But do you think Pete picked up on that? No sir. He went right on rubbing and purring and winding his tail around the boy's legs, I mean, it looked like a bullsnake climbing a tree.

Little Alfred stumbled over the cat, which is what usually happens. He stopped and looked down. A gleam came into his eyes and a smile spread across his mouth.

Up went the rope. Three twirls later, a nice little loop sailed out and dropped over Pete's head, just as pretty as you please.

I barked, wagged my tail, and jumped up and down. I mean, I could hardly contain my pride and enthusiasm. Did I say the boy couldn't rope? Couldn't hit a bull in the behind with a bass fiddle? Fellers, he had just one-looped a cat, and I couldn't have been prouder if I'd done it myself!

Well, you know Pete, sour-puss and can't-take-a-joke. He pinned his ears down, growled, hissed, and made a dash for the iris patch. Ho ho! Did he come to a sudden stop? Yes he did. Hit the end of that twine, came to a sudden stop, and did a darling little back flip.

Little Alfred beamed a smile at me. “I woped a cat!”

I barked and wagged and gave him my most sincere congratulations on a job well done.

He reeled the cat in. By this time, old Pete had quit fighting the rope and had sulled up. His ears were still pinned down and he was making that police-siren growl that cats make when they ain't real happy about the state of the world.

Alfred picked him up, opened the gate, and joined me on the other side, guess he wanted to show me his trophy. I gave him a big juicy lick on the face and was about to . . .

HUH?

The little snipe! Now, why did he go and pitch the cat on me? Hey, I'd been on his side all along. I'd been out there cheering him on and trying to coach . . .

All at once, Pete wasn't sullen anymore. He'd turned into a buzz saw, and before I even knew what was happening, he'd stung me in fifteen different places, and we're talking about very important places such as my eyebrows, cheeks, gums, lips, ears, and the soft part of my nose.

Did it hurt? You bet it hurt, and never mind who'd started this riot, I was fixing to introduce Pete to an old cowdog technique called “Disaster.” I barked and I snarled and I growled and I snapped . . .

“HANK, YOU BULLY, GET AWAY FROM MY CAT!!”

Huh?

Get away from . . . no doubt that voice belonged to Sally May and . . . perhaps she thought . . .

I cancelled my plans for hamburgerizing the cat, and prepared to thump my tail on the ground and give her an innocent smile.

At the time, I didn't know that she was already upset about the missing eggs. But I soon found out.

Chapter Three: The Case of the Missing Eggs

S

he came storming down the hill, carrying the egg bucket in her left hand. Right hand. Who cares?

Carrying the egg bucket in one hand and with the other she held Baby Molly. No doubt the two of them had been up at the chicken house, gathering eggs. (That explained the egg bucket, see.)

She reached the bottom of the hill and set the egg bucket down on the ground beside me. Naturally, I peered inside and gave the bucket a sniffing, with no thought or intention of . . . some dogs will eat eggs, don't you see, and they're known as Egg-Sucking Dogs and they ain't popular with ranch wives or whoever else is in charge of the . . .

Nothing could have been further from my mind. Honest. Cross my heart and hope to die. I have flaws, but sucking eggs has never been one of them, although I must admit that at certain times of the day and certain times of the year, a nice fresh egg . . .

She speared me with her eyes. “Don't you even THINK about messing with my eggs!”

Who, me? Now, what had . . . all I'd . . . there was no reason to . . .

Sometimes the best thing a guy can do is just keep his mouth shut and take a telling, even when it involves stuffing down his sense of mortal outrage. In the process of stuffing down the so forth, I sniffed again. It was just a mannerism, it meant nothing at all, but Sally May took it all wrong and turned it into something that was blown all out of . . .

“Stop smelling my eggs because they're not for you!”

Okay, okay. But for what it's worth, they smelled pretty good, although that wasn't my primary . . .

Let me repeat that I am not now and never have been an egg-sucking dog, and that's my last word on the subject. For a while.

At that moment, High Loper came up the hill. He'd been down at the barn doing his morning chores, which at that time of the year meant feeding one saddle horse and a two-year-old colt. The rest of the horses were grazing on grass.

He walked up to us, swept his eyes over me, the cat, and Little Alfred, and grinned. “Well, well, what do we have cooking here?”

Sally May placed both hands on her hips. “Your son and your dog. You see what they're doing?”

Little Alfred beamed, as all eyes turned to him. “I woped me a cat, Daddy.”

“Yes,” Sally May went on, “he roped my poor cat and then threw him on your dog, just to see what would happen.”

Loper chuckled. “What happened?”

“You know very well what happened. If I hadn't come down just when I did, Hank would have brutalized the cat.”

“From the looks of the blood, hon, it was the other way around. It looks like your cat brutalized my poor dog.”

She glanced down at me. I wagged my tail extra hard. I was disappointed to see her smile. “He did take a few licks, didn't he, but I'm sure he deserved them. Now, will you speak to your son about starting cat-and-dog fights?”

Loper knelt down and gave Alfred a lecture about roping cats and starting fights, although I got the feeling that Loper might have participated in the same sports when he was young.

“Oh,” said Sally May, “and while we're on the subject of your dog, I found seven broken eggs in the chicken house this morning.

Something

got in there last night,” she turned a dark glare in my direction, “and is eating my eggs.”

I turned away, astonished that she might think . . .

Loper stood up, and as usual his knees popped three times. “Now hold on. What makes you think Hank had anything to do with it?”

“Well . . . I don't know. Nothing really, except that he has a lousy reputation around here, and anytime there's a mess or some trouble, he's a prime suspect.”

Her words cut me to the crick. It was really tough to sit there and listen to such falsehoods and never say a word in my own defense. I managed to keep silent, but just barely.

“I doubt that Hank's the culprit, hon. More than likely, it was a skunk or a bullsnake, but just because you're such a sweet and gorgeous thang, I'll go up and check it out.”

He gave her a kiss on the cheek.

“Well, that's nice. Thank you. I'll be much sweeter and more gorgeous if I can get my twelve eggs a day.”

With that, she herded her two children into the yard, un-noosed the cat, and disarmed Little Alfred. Loper and I went up the hill to chick out the checking house. Chicken house. Check out the chicken house.

As we passed the big sliding doors of the maÂchine shed, whose nose do you suppose poked out of the crack between the doors? It was Mister Scared-He'd-Get-Roped.

“Hi Hank, looks like we might get some rain, huh?” I ignored him, so naturally he came out and fell in step beside me. “Where we going?”

“I don't know where

you're

going, but Loper and I are going to the chicken house on important business.”

“Oh good.”

“But I'd just as soon not be seen with you, after the way you ran from that rope.”

“Yeah, that was quite a rope.”

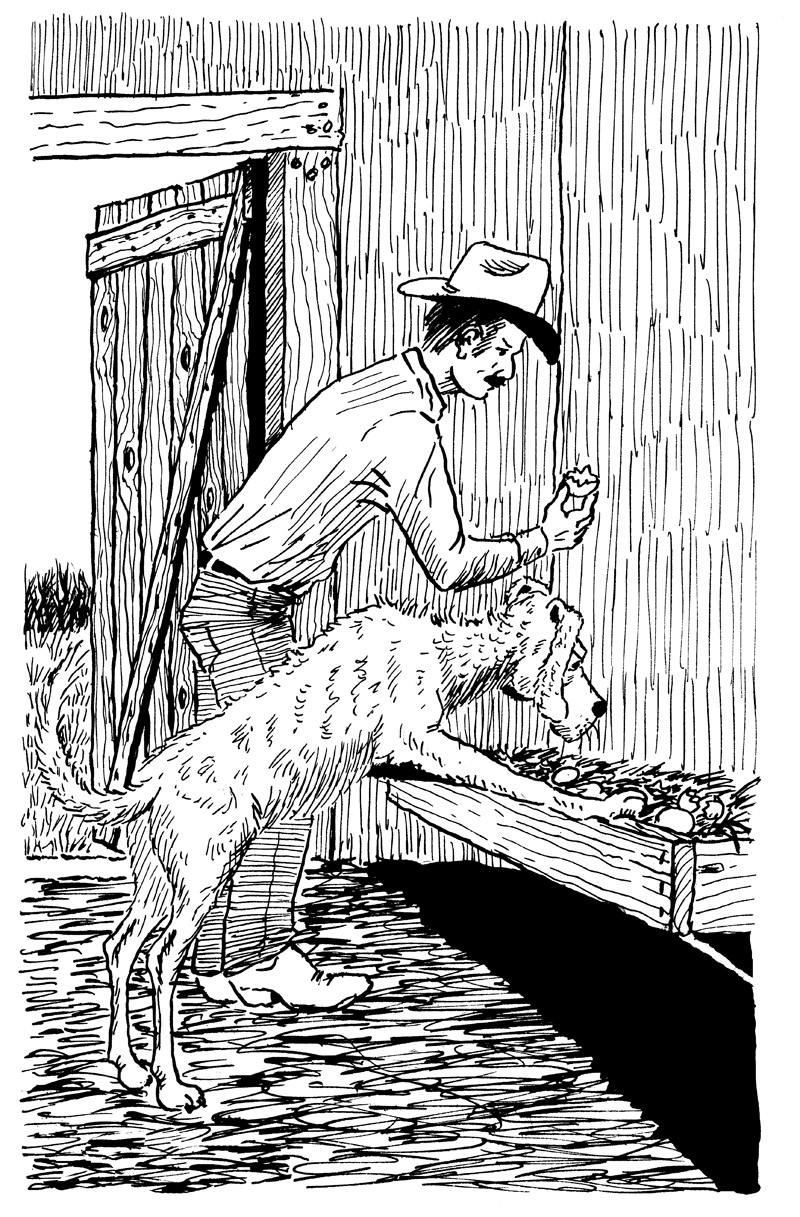

By this time, Loper had reached the chicken house. He pushed open the big door on the east. The chickens never used this door, for the simple reason that chickens are unable to turn doorknobs and push open large doors. They came and went through a small opening near the center of the building.

I was already studying the layout of the alleged chicken house, committing every detail of its construction to memory, amassing facts and clues, and sending it all to Data Control. A guy never knows which tiny fact will be the one that breaks a case wide open.

Loper stepped inside, causing the hens to squawk and flutter. I followed one step behind, put my nose to the floor and began . . .

You ever try to sniff out a scent in a chicken house? You should try it sometime, just put your nose to the floor and take a deep breath. When you regain consciousness, you'll realize that even an elephant could hide his scent in a chicken house.

My nose is a very sensitive smellatory instrument, see, and it's calibrated to pick up SUBTLE odors. There are many odors in a chicken house, none of them subtle. One whiff of that place blew out all my circuits.

When I stopped coughing, I was able to mutter, “Boy, this is a foul place!”

“Yeah,” said Drover, “they're just birds.”

“What?”

“I said, fowls are just birds. That's how come they're in a chicken house.”

Sometimes . . . oh well. I had more important things to do than to make sense of Drover's nonsense.

Loper was bending over one of the nests, which was located inside a wooden crate. I hopped up and studied the contents of the nest. There, lying amidst the straw, were pieces of egg shell.

Loper moved on down the line and found other nests with broken eggs. Then he straightened up, worked a kink out of his back, and pushed his straw hat to the back of his head.

“Well, dogs, something's been robbing these nests.” I barked. Now we were getting somewhere. “It wasn't a bullsnake, because a snake wouldn't have left the shells in the nest.

“It looks like the work of a skunk, but if it had been a skunk, he would have left a scent behind. That leaves a coon or a coyote. The next question is, where were you fools when the coyote or coon came into headquarters?”

Huh? Well, it was a big ranch and . . .

“Let's just say that if I find any more busted eggs, I might start thinking about my dog food bill. I might just run the cost of gain on you mutts and decide to cut down on my overhead.”

He leaned down and brought his face real close to mine. “Do you understand what I'm saying? No more busted eggs. No more angry wife. No more varmints in the chicken house. Tend to your business!”

Tend to . . . what did he think we'd . . . but, yes, the message had come through loud and clear, so loud and so clear that I left the chicken house shaking all over.

If you happen to be a dog, the prospect of life without dog food can be rather bleak. We had a job to do, fellers, and we dared not fail.