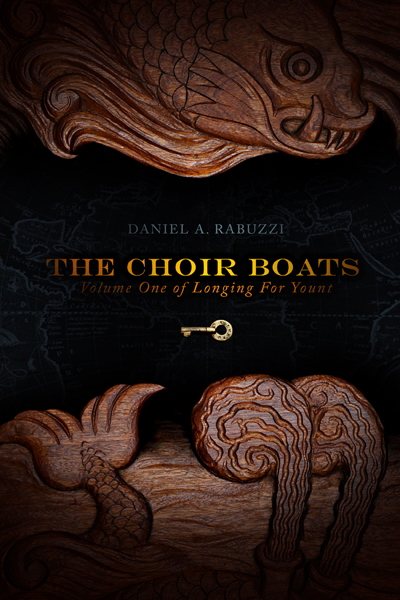

The Choir Boats

FIRST EDITION

The Choir Boats © 2009 by Daniel A. Rabuzzi

Cover wood carving and chapter illustrations © 2009 by Deborah A. Mills

Wood carving photograph © 2009 by Shira Weinberger

Jacket design © 2009 by Erik Mohr

All Rights Reserved.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either a product of

the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblances to actual events, locales,

or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Rabuzzi, Daniel A. (Daniel Allen), 1959-

The choir boats / Daniel A. Rabuzzi ; editors: Alexander Savory & Sandra

Kasturi ; illustrators: Erik Mohr & Deborah Mills.

(Longing for Yount ; v. 1)

ISBN 978-0-9809410-6-7 (bound).--ISBN 978-0-9809410-7-4 (pbk.)

I. Savory, Brett Alexander, 1973- II. Kasturi, Sandra, 1966- III. Title.

IV. Series: Rabuzzi, Daniel A. (Daniel Allen), 1959- . Longing for Yount ; v. 1.

PS3618.A328C47 2009; 813’.6; C2009-903617-7

CHIZINE PUBLICATIONS

Toronto, Canada

www.chizinepub.com

Edited by Brett Alexander Savory

Copyedited and proofread by Sandra Kasturi

Converted to mobi and epub by Christine http://finding-free-ebooks.blogspot.com/

,

For notes to the text, and other background information on the

McDoons and Yount, see: www.danielarabuzzi.com

Dedicated to my two brothers, Matt and Doug, and my five nephews,

Nick, Patrick, Than, Terence, and James.

The young woman counted — “

Otu

,

abua

,

ato

,

ano

,

ise

,

isii

,

asaa

” —

using what remained to her of the secret language her mother had

learned from

her

father, the language they had used in the place

across the ocean when they did not want the white men with whips

to understand. “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven . . . we need

seven to succeed, seven to open the way.

Chi di

, there is still daylight

left, still time, but not much.”

She stood near dusk in a blind alley in Whitechapel on the verge

of the City of London. Distant notes drifted down from the sliver

of sky far above, bells tolling the Feast of the Epiphany on the first

Sunday in 1812. The young woman (little more than a girl, perhaps

sixteen years of age) pulled her worn-out sailor’s coat around her and

knotted her red kerchief against the cold. She scratched numbers on

the brick wall in front of her, deepening the grooves made hundreds

of times before. Staring at the numbers until the bricks faded, until

she could see deep into herself and beyond, the girl hummed.

Rooks flew over rooftops but she did not heed their calls. She was on the marches of

ala mmuo

, the realm of the spirits. There she met the

ancestors, the

ndichie

, who spoke of pride burnished under the sun, the

heart of courageous healing, the brown eye of wisdom. Today she went

farther than she ever had before, led on by the humming of a thousand

bees at a thousand bee-ships, until she neared the border to another

land. The moon in that place illuminated a row of pillars on a ridge in

the distance, pillars topped with watching creatures. One shape lifted

itself off a pillar, a white owl as large as a house, an owl with a swallow’s

tail streaming behind it as it flew towards her. The young woman fled

the owl’s reshing beak, escaped from the borderland, turned back to see

the owl circling at an invisible threshold. Its cry pierced the humming,

followed her as she tumbled away.

Falling, she caught a glimpse of a young white woman reading

by candlelight in an attic. A golden cat sat in the white woman’s

lap. The walls of the attic leaned inward, the roof sagging like a

thumb seeking an insect to squash. The white woman thrust the

book up against the room’s slow throttle; the cat arched its back

and spat. The candle flame shrank. The white woman threw back

her head and opened her mouth, trying to sing but only gasping.

The candle went out.

The woman in the alley ceased humming, fell back into herself.

Before she awoke fully to her body, she heard the beating of a great

drum and the booming of a great bell — a drum with eyes and a

bell rimmed by living fire, out of which came a voice soothing and

powerful, neither male nor female yet both at the same time.

“

Uche chukwu ga-eme

, God’s will shall be done,” intoned the voice

in the secret language and in English. “Seven singers for turning to

the people a pure language. ‘But who shall lead them? From beyond

the rivers of Ethiopia and Cush, the daughter of the dispersed . . .’”

A figure emerged in the mist on Mincing Lane. He wore a coat from the

previous century, a reddish coat that seemed to shift with the vagaries

of the fog. Porters, carriage-men and servants passed him by but would

be hard-pressed to describe him in that instant and had forgotten him

entirely by the time they reached their destinations. Only the rooks

wheeling overhead in the late-afternoon sky might have known what

the man was, but no one understands their calls. Unheeded, the rooks

returned to their towers as the church bells ceased tolling for the Feast

of the Epiphany on the first Sunday of 1812.

The man in the crimson coat scanned Mincing Lane, a

thoroughfare between Fenchurch Street and Great Tower Street not

far from the Thames in the City of London. He found the three-story

counting house of a merchant, unremarkable except for its dolphin-shaped door knocker and pale blue window trim. Without removing

his gaze from the house, he took from one pocket a shrivelled apple.

Fastidiously, he ate. His eyes took in the house, knowing as they

already did every angle and every surface. Keeping pace with his

eyes, his tongue and teeth delicately destroyed the fruit.

He was down to the core when the first light came on in the

house. One window glowed in the mist, flickered as someone inside

crossed the candle. He stopped eating, apple core held like a half-moon twixt finger and thumb. A candle was lighted in an attic room,

illuminating a golden cat sitting on the window sill. The man’s coat

undulated, restless and ruddy. Night came. The cold increased but

the coat-man disregarded it; he had been much colder before.

Very faint, the man heard a hum in the back of his mind. Eyes

still on the house, he sought inward and outward and round-ward,

chasing the source of the sound. No good. The ghost whisper of

a hum faded, eluding him as it had for a long age of this earth.

Somewhere above the fog the moon rose. The house — moored and

complacent — was unaware of him, or aware only as a sleeper is, in

some deep recess of thought beyond waking.

The man in the coat swallowed the core in one bite. “Soon,” he

said to the house. The next moment, he was gone.

London merchant Barnabas Eusebius Playdermon McDoon received

a box at his Mincing Lane house on the first Monday of 1812.

Sanford, the firm’s other partner, a man of few hairs and fewer

words, said the box had come in the morning post but no one knew

its origin. Barnabas pushed aside the letter he had been writing to

their Bombay factor about the Hamburg and Copenhagen markets

for smilax root, pepper and mastic gum. The interruption pleased

Barnabas: he had fretted all morning, his irritation mounting as

he wrote about stratagems and manoeuvres in the North Sea that

he would not be able to execute in person. He was tired of waging

tabletop battles between his inkpot and his snuffbox. He longed for

the cardamom whispers he thought he heard just around the corner

of deserted streets, the minarets and elephants he thought he saw

reflected in shop windows. He desired to exorcise the ghost of guilt

and the memory of actions undone, a love abandoned.