The Code Book (33 page)

For some, the publication of Winterbotham’s book came too late. Many years after the death of Alastair Denniston, Bletchley’s first director, his daughter received a letter from one of his colleagues: “Your father was a great man in whose debt all English-speaking people will remain for a very long time, if not forever. That so few should know exactly what he did is the sad part.”

Alan Turing was another cryptanalyst who did not live long enough to receive any public recognition. Instead of being acclaimed a hero, he was persecuted for his homosexuality. In 1952, while reporting a burglary to the police, he naively revealed that he was having a homosexual relationship. The police felt they had no option but to arrest and charge him with “Gross Indecency contrary to Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885.” The newspapers reported the subsequent trial and conviction, and Turing was publicly humiliated.

Turing’s secret had been exposed, and his sexuality was now public knowledge. The British Government withdrew his security clearance. He was forbidden to work on research projects relating to the development of the computer. He was forced to consult a psychiatrist and had to undergo hormone treatment, which made him impotent and obese. Over the next two years he became severely depressed, and on June 7, 1954, he went to his bedroom, carrying with him a jar of cyanide solution and an apple. Twenty years earlier he had chanted the rhyme of the Wicked Witch: “Dip the apple in the brew, Let the sleeping death seep through.” Now he was ready to obey her incantation. He dipped the apple in the cyanide and took several bites. At the age of just forty-two, one of the true geniuses of cryptanalysis committed suicide.

5 The Language Barrier

While British codebreakers were breaking the German Enigma cipher and altering the course of the war in Europe, American codebreakers were having an equally important influence on events in the Pacific arena by cracking the Japanese machine cipher known as Purple. For example, in June 1942 the Americans deciphered a message outlining a Japanese plan to draw U.S. Naval forces to the Aleutian Islands by faking an attack, which would allow the Japanese Navy to take their real objective, Midway Island. Although American ships played along with the plan by leaving Midway, they never strayed far away. When American cryptanalysts intercepted and deciphered the Japanese order to attack Midway, the ships were able to return swiftly and defend the island in one of the most important battles of the entire Pacific war. According to Admiral Chester Nimitz, the American victory at Midway “was essentially a victory of intelligence. In attempting surprise, the Japanese were themselves surprised.”

Almost a year later, American cryptanalysts identified a message that showed the itinerary for a visit to the northern Solomon Islands by Admiral Isoruko Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Fleet. Nimitz decided to send fighter aircraft to intercept Yamamoto’s plane and shoot him down. Yamamoto, renowned for being compulsively punctual, approached his destination at exactly 8:00

A.M.

, just as stated in the intercepted schedule. There to meet him were eighteen American P-38 fighters. They succeeded in killing one of the most influential figures of the Japanese High Command.

Although Purple and Enigma, the Japanese and German ciphers, were eventually broken, they did offer some security when they were initially implemented and provided real challenges for American and British cryptanalysts. In fact, had the cipher machines been used properly—without repeated message keys, without cillies, without restrictions on plugboard settings and scrambler arrangements, and without stereotypical messages which resulted in cribs—it is quite possible that they might never have been broken at all.

The true strength and potential of machine ciphers was demonstrated by the Typex (or Type X) cipher machine used by the British army and air force, and the SIGABA (or M-143-C) cipher machine used by the American military. Both these machines were more complex than the Enigma machine and both were used properly, and therefore they remained unbroken throughout the war. Allied cryptographers were confident that complicated electromechanical machine ciphers could guarantee secure communication. However, complicated machine ciphers are not the only way of sending secure messages. Indeed, one of the most secure forms of encryption used in the Second World War was also one of the simplest.

During the Pacific campaign, American commanders began to realize that cipher machines, such as SIGABA, had a fundamental drawback. Although electromechanical encryption offered relatively high levels of security, it was painfully slow. Messages had to be typed into the machine letter by letter, the output had to be noted down letter by letter, and then the completed ciphertext had to be transmitted by the radio operator. The radio operator who received the enciphered message then had to pass it on to a cipher expert, who would carefully select the correct key, and type the ciphertext into a cipher machine, to decipher it letter by letter. The time and space required for this delicate operation is available at headquarters or onboard a ship, but machine encryption was not ideally suited to more hostile and intense environments, such as the islands of the Pacific. One war correspondent described the difficulties of communication during the heat of jungle battle: “When the fighting became confined to a small area, everything had to move on a split-second schedule. There was not time for enciphering and deciphering. At such times, the King’s English became a last resort—the profaner the better.” Unfortunately for the Americans, many Japanese soldiers had attended American colleges and were fluent in English, including the profanities. Valuable information about American strategy and tactics was falling into the hands of the enemy.

One of the first to react to this problem was Philip Johnston, an engineer based in Los Angeles, who was too old to fight but still wanted to contribute to the war effort. At the beginning of 1942 he began to formulate an encryption system inspired by his childhood experiences. The son of a Protestant missionary, Johnston had grown up on the Navajo reservations of Arizona, and as a result he had become fully immersed in Navajo culture. He was one of the few people outside the tribe who could speak their language fluently, which allowed him to act as an interpreter for discussions between the Navajo and government agents. His work in this capacity culminated in a visit to the White House, when, as a nine-year-old, Johnston translated for two Navajos who were appealing to President Theodore Roosevelt for fairer treatment for their community. Fully aware of how impenetrable the language was for those outside the tribe, Johnston was struck by the notion that Navajo, or any other Native American language, could act as a virtually unbreakable code. If each battalion in the Pacific employed a pair of Native Americans as radio operators, secure communication could be guaranteed.

He took his idea to Lieutenant Colonel James E. Jones, the area signal officer at Camp Elliott, just outside San Diego. Merely by throwing a few Navajo phrases at the bewildered officer, Johnston was able to persuade him that the idea was worthy of serious consideration. A fortnight later he returned with two Navajos, ready to conduct a test demonstration in front of senior marine officers. The Navajos were isolated from each other, and one was given six typical messages in English, which he translated into Navajo and transmitted to his colleague via a radio. The Navajo receiver translated the messages back into English, wrote them down, and handed them over to the officers, who compared them with the originals. The game of Navajo whispers proved to be flawless, and the marine officers authorized a pilot project and ordered recruitment to begin immediately.

Before recruiting anybody, however, Lieutenant Colonel Jones and Philip Johnston had to decide whether to conduct the pilot study with the Navajo, or select another tribe. Johnston had used Navajo men for his original demonstration because he had personal connections with the tribe, but this did not necessarily make them the ideal choice. The most important selection criterion was simply a question of numbers: the marines needed to find a tribe capable of supplying a large number of men who were fluent in English and literate. The lack of government investment meant that the literacy rate was very low on most of the reservations, and attention was therefore focused on the four largest tribes: the Navajo, the Sioux, the Chippewa and the Pima-Papago.

The Navajo was the largest tribe, but also the least literate, while the Pima-Papago was the most literate but much fewer in number. There was little to choose between the four tribes, and ultimately the decision rested on another critical factor. According to the official report on Johnston’s idea:

The Navajo is the only tribe in the United States that has not been infested with German students during the past twenty years. These Germans, studying the various tribal dialects under the guise of art students, anthropologists, etc., have undoubtedly attained a good working knowledge of all tribal dialects except Navajo. For this reason the Navajo is the only tribe available offering complete security for the type of work under consideration. It should also be noted that the Navajo tribal dialect is completely unintelligible to all other tribes and all other people, with the possible exception of as many as 28 Americans who have made a study of the dialect. This dialect is equivalent to a secret code to the enemy, and admirably suited for rapid, secure communication.

At the time of America’s entry into the Second World War, the Navajo were living in harsh conditions and being treated as inferior people. Yet their tribal council supported the war effort and declared their loyalty: “There exists no purer concentration of Americanism than among the First Americans.” The Navajos were so eager to fight that some of them lied about their age, or gorged themselves on bunches of bananas and swallowed great quantities of water in order to reach the minimum weight requirement of 55 kg. Similarly, there was no difficulty in finding suitable candidates to serve as Navajo code talkers, as they were to become known. Within four months of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 29 Navajos, some as young as fifteen, began an eight-week communications course with the Marine Corps.

Before training could begin, the Marine Corps had to overcome a problem that had plagued the only other code to have been based on a Native American language. In Northern France during the First World War, Captain E.W. Horner of Company D, 141st Infantry, ordered that eight men from the Choctaw tribe be employed as radio operators. Obviously none of the enemy understood their language, so the Choctaw provided secure communications. However, this encryption system was fundamentally flawed because the Choctaw language had no equivalent for modern military jargon. A specific technical term in a message might therefore have to be translated into a vague Choctaw expression, with the risk that this could be misinterpreted by the receiver.

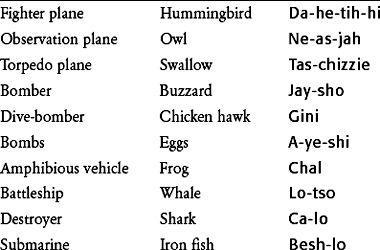

The same problem would have arisen with the Navajo language, but the Marine Corps planned to construct a lexicon of Navajo terms to replace otherwise untranslatable English words, thus removing any ambiguities. The trainees helped to compile the lexicon, tending to choose words describing the natural world to indicate specific military terms. Thus, the names of birds were used for planes, and fish for ships (

Table 11

). Commanding officers became “war chiefs,” platoons were “mud-clans,” fortifications turned into “cave dwellings” and mortars were known as “guns that squat.”

Even though the complete lexicon contained 274 words, there was still the problem of translating less predictable words and the names of people and places. The solution was to devise an encoded phonetic alphabet for spelling out difficult words. For example, the word “Pacific” would be spelled out as “pig, ant, cat, ice, fox, ice, cat,” which would then be translated into Navajo as bi-sodih, wol-la-chee, moasi, tkin, ma-e, tkin, moasi. The complete Navajo alphabet is given in

Table 12

. Within eight weeks, the trainee code talkers had learned the entire lexicon and alphabet, thus obviating the need for codebooks which might fall into enemy hands. For the Navajos, committing everything to memory was trivial because traditionally their language had no written script, so they were used to memorizing their folk stories and family histories. As William McCabe, one of the trainees, said, “In Navajo everything is in the memory—songs, prayers, everything. That’s the way we were raised.”

Table 11

Navajo codewords for planes and ships.

At the end of their training, the Navajos were put to the test. Senders translated a series of messages from English into Navajo, transmitted them, and then receivers translated the messages back into English, using the memorized lexicon and alphabet when necessary. The results were word-perfect. To check the strength of the system, a recording of the transmissions was given to Navy Intelligence, the unit that had cracked Purple, the toughest Japanese cipher. After three weeks of intense cryptanalysis, the Naval codebreakers were still baffled by the messages. They called the Navajo language a “weird succession of guttural, nasal, tongue-twisting sounds … we couldn’t even transcribe it, much less crack it.” The Navajo code was judged a success. Two Navajo soldiers, John Benally and Johnny Manuelito, were asked to stay and train the next batch of recruits, while the other 27 Navajo code talkers were assigned to four regiments and sent to the Pacific.