The Cold War: A MILITARY History (29 page)

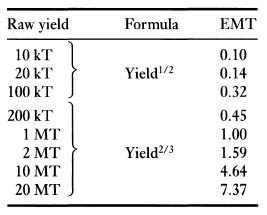

For yields of 200 kT and above: EMT = yield

2/3

For yields of less than 200 kT: EMT = yield

1/2

Table 14.1

Equivalent megatonnage

Table 14.1

shows a ‘law of diminishing returns’ operating, where, for example, a tenfold increase in raw yield from 1 MT to 10 MT results in less than a fivefold increase in EMT.

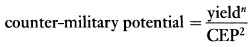

EMT does not, however, make any allowance for accuracy (CEP), which is an important consideration when attacking pinpoint targets such as missile silos. This requires a more sophisticated measure to assess weapon

lethality

or

counter-military potential

(CMP):

where

n

= 2/3 for yields of 200 kT and above

n

= 4/5 for yields of less than 200 kT

and | CEP is measured in nautical miles. |

Thus the greater the accuracy (i.e. the smaller the CEP), the greater will be the CMP; in fact the lethality increases much more rapidly with accuracy than it does with yield.

It follows from this that the ability of a country to destroy an opponent’s missiles in their silos is the product of the CMP and the total number of warheads:

i.e. | total CMP = CMP × number of warheads |

AVAILABILITY

The simple fact that a missile existed was not, however, the whole story, and two further factors came into play in assessing whether or not a missile was likely to achieve its purpose: availability and reliability.

Availability was an assessment of whether or not a weapons system would be ‘ready to go’ at the moment it was required, and was a function of factors such as a missile’s having been taken ‘off-line’ for maintenance, or removed altogether either to be modernized or for the silo to be rebuilt to meet greater hardness criteria, and so on. If a missile was unavailable, then so too were its warheads, making a difference of one potential target in the case of a single-warhead missile, but of up to ten or even fourteen where the missile was fitted with multiple warheads (MRVs or MIRVs).

One factor which could have increased the number of missiles available was the use of at least some of the apparently non-operational stocks. Thus an SSBN in port undergoing a short refit between patrols might have been brought up to operational status within forty-eight hours and could either have put to sea rapidly or, in the worst case, have fired its missiles while still

lying

alongside. Some navies also operated trials submarines (e.g. the French

Gymnote

and the single Chinese Golf-class) which could have launched missiles in a wartime emergency.

Land-based test centres existed to test prototypes and, at least in the US case, were also used for routine testing of operational missiles. They thus obviously had full-scale launch facilities which could be used to generate additional missile launches in war. The US Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, for example, was capable of launching up to sixteen missiles,

1

while there were launch facilities for Chinese DF-4s at various test centres in China, for Russian missiles at similar sites in the USSR, and for four French SSBS S3D missiles at the Centre d’Essais des Landes (CEL) test facility for land-based missiles, in south-west France.

RELIABILITY

Reliability, on the other hand, was an assessment of the probability that available systems would function correctly from the moment of issuing the launch instruction to the arrival of a warhead at the target. The general approach to determining the probability of success for a complex operation was to break it down into a sequence of discrete events and to determine the probability of the successful outcome of each one, normally expressed as a percentage. All these probabilities were then multiplied together to give the overall probability of success – i.e. the probability that the missile would accomplish its mission. Thus, for example, a missile with ten discrete functions (first stage motor fires, missile leaves silo, second stage motor fires, second stage separates from first stage, and so on), each with a 98 per cent probability of success, has an overall reliability factor of (98 ÷ 100)

10

= 82 per cent.

One problem with the reliability equation was that it was impracticable to test the missiles on their operational flight paths. US test flights, for example, were in either south-easterly or south-westerly directions or due south, whereas the operational flights would have been to the north, north-west or north-east. Similarly, Soviet test flights were not in the direction required for operational flights, although the huge land mass of the USSR enabled Soviet strategic rocket forces to carry out regular missile testing using live missiles fired from their operational silos, whereas US ICBMs had to be taken to Vandenberg Air Force Base. Thus it was possible that, had they ever been launched in anger, missile guidance systems might have been influenced by some unexpected factor, such as a minor variation in the earth’s magnetic field, for which no allowance had been made. This might well not have had a significant effect on a counter-value mission, but could have caused just sufficient variation in a counter-force mission to make the difference between success and failure.

Although SSBNs frequently launched SLBMs with inert heads, there was only one known example of a fully operational SSBN/SLBM launch with a nuclear warhead. Designated ‘Frigate Bird’, this took place in the Pacific Ocean on 6 May 1962, when USS

Ethan Allen

(SSBN-608) launched a Polaris A-2 missile with a W47 warhead. The test, which was successful, involved a flight of 1,890 km from the submerged launch, culminating in an airburst over Christmas Island.

Numerous operational examples occurred to show that missiles were neither as available nor as reliable as may have been thought. The US navy’s Poseidon C-3 had severe reliability problems in the early 1970s, and there were several reports that missiles had failed to fire during routine tests. A significant number of Poseidons’ W68 warheads were also reported to have been defective, due to degradation of the high-explosive element, one effect of which could have been the failure of the detonator.

2

Although unconfirmed at the time, the US navy subsequently tacitly endorsed these reports by stating that the Trident II C-4 had a ‘much better reliability record’ than the Poseidon C-3.

In an incident in 1986, an unarmed Soviet navy SS-N-8 was test-fired by a Delta II SSBN in the Barents Sea and aimed at the missile test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula, but landed near the Amur river on the Sino-Soviet border, some 2,400 km from its target. Since missile are always carefully checked and prepared for test flights, such a major deviation from the intended flight path caused considerable concern at the time.

3

Another incident, much publicized at the time, occurred in October 1986, when a Soviet Yankee-class SSBN suffered serious structural damage as a result of an explosion in one of the missile tubes, presumably involving the highly volatile liquid fuels. In another incident a Soviet Delta IV-class SSBN attempted to launch sixteen SS-N-23 missiles one after another in the White Sea on 7 December 1989. The third missile failed very soon after launch and fell back on to the submarine (which presumably was on the surface) and thirteen men were injured.

According to Russian sources, the SS-N-4 SLBM was in service between 1961 and 1973, and during that time 311 test launches were made. Of those launches, there were 38 missile failures, 38 failures due to other known causes, and 10 due to unknown causes. In other words, only 72.3 per cent (225) of the missiles were successful, and that was without a live warhead, which would have introduced yet another element of uncertainty.

4

SINGLE-SHOT KILL PROBABILITY

Single-shot kill probability (SSKP) is an expression of the probability that one warhead of specified reliability will destroy a hardened target. Thus it

can

be calculated that a single warhead of 0.5 MT yield, a CEP of 260 m and a reliability of 85 per cent, attacking a target capable of withstanding an overpressure of 146 kgf/cm

2

, would have an SSKP of 54 per cent. In other words, the warhead has a marginally better than ‘evens’ chance of success.

CAPABILITIES

As explained earlier, a true assessment of the nuclear balance would require a detailed analysis of a vast array of variable factors, and would need to include allowances for factors such as availability, reliability, differing practices in SSBN sea-time, the weather at both launch sites and targets, and so on. It would also need to take account of each side’s targeting plans, including how many warheads might be allocated to the first and second strikes, how many might be classified as ‘withholds’, how many might be retained as strategic and ‘

n

th-country reserves’, and so on. Determining such a balance would also require individual missile systems to be split between counter-value and counter-force targets.

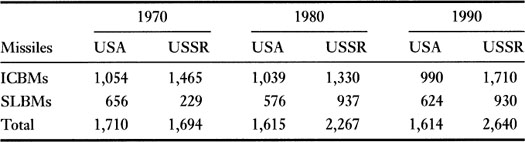

With so many factors to be taken into account, a powerful computer would be needed to calculate the final result, which would need to be accompanied by long and detailed explanations. However,

Tables 14.2

to

14.4

show a general picture of the situation by taking three ‘snapshots’ of the situation in 1970, at which time the missile race was really under way, in 1990, at the end of the Cold War, and in 1980, halfway between the two.*

Table 14.2

The Strategic Balance – Missiles

fn1

Table 14.2

shows the balance in numbers of missiles. The number of ICBMs shows the total number of land-based missiles, which (ignoring dummy silos) was also the majority of targets the enemy would have needed to destroy in a pre-emptive strike (the others being a relatively small number of command-and-control sites). In ICBMs, both sides showed a fairly steady figure, the 1990 reduction in US ICBMs being due to the retirement without

replacement

of the Titan II. In SLBM numbers, the USA had already peaked in numbers by 1970 and retained a reasonably steady state thereafter, while the USSR grew rapidly from 35 per cent of the US figure in 1970 to 163 per cent a decade later, as the many Delta-class SSBNs entered service.

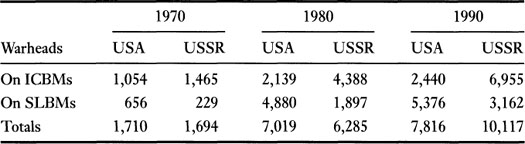

Table 14.3

The Strategic Balance – Warheads