The Cold War: A MILITARY History (6 page)

Unlike other potential members, Portugal was a dictatorship, and was not invited to join the Washington talks until early 1949. Portugal stipulated that accession to the treaty would not mean that it would accept foreign troops stationed on its territory (Norway had stipulated likewise), although US bases were permitted in the strategically important Azores.

France, as usual during this period, was beset by domestic political problems. In early 1947 the government was formed from a coalition of centrist parties, and on 4 May the prime minister, the Socialist Paul Ramadier, dismissed Maurice Thorez and three other Communists from government. Despite these upheavals, France joined the United Kingdom in the Dunkirk Treaty and shared the lead with the United Kingdom in finalizing the Brussels Treaty. In 1949 the new prime minister, Henri Queuille, said that the United States must not allow France and western Europe to be invaded by the Soviet Union as they had been by Germany, and also added that the defence of western Europe must start on the Elbe (i.e. the border between the Soviet and Anglo-US zones of occupation). Not surprisingly, the French Communists were greatly opposed to the North Atlantic Treaty, but it went to the National Assembly on 17 May and was approved on 27 July.

United States’ membership of a peacetime European defence pact was by no means a foregone conclusion either, and one of the key factors in any US involvement had to be the agreement of the US Congress. Here the master stroke was the decision to ‘allow’ the Senate to take the initiative. Thus was born the ‘Vandenberg Resolution’, which, like many things in NATO’s birth, went through the governmental system in an exceptionally short time. Thus, the first discussions were held with Senator Arthur Vandenberg, chairman of the powerful Senate Foreign Relations Committee, on 11 April, a draft was first considered by the Foreign Relations Committee on 11 May, and it was passed by the Senate (by a majority of 64 to 6) on 11 June 1948. The resolution recommended that the president should pursue:

progressive development of regional and other collective arrangements for individual and collective self-defense in accordance with the principle and provisions of the [United Nations] charter.

Association of the United States by constitutional process with such regional and other collective arrangements as are based on continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid, and as affect its national security.

Contribution to the maintenance of peace by making clear its determination to exercise the right of individual or collective self-defense under Article 51 [of the UN Charter] should any armed attack occur affecting its national security.

1

Several other countries were considered for membership during the original negotiations, but their cases were either postponed or rejected for one reason or another. It was recognized from the start that West German membership would be inevitable, but would not be appropriate in the first instance. Similarly, it was always intended that Greece, Turkey and Spain would eventually become members.

There was some discussion of the NATO guarantee of mutual defence being extended to cover Belgian, British, Dutch and French overseas possessions. The countries concerned allowed this suggestion to be quietly dropped, except that the ‘Algerian Departments of France’ were included in Article 6 and Danish membership was always understood to include Greenland.

The Republic of Ireland had remained neutral throughout the war and had denied the Allies the use of any facilities such as ports and airfields. In spite of this, the UK was keen for Eire to join the proposed Atlantic pact, and the Irish government was invited to attend the negotiations in mid-1948. When, however, the Irish government replied that it would join the discussions only if the UK promised to transfer the Six Counties (the predominantly Protestant North) to the Republic of Ireland, the matter was immediately dropped and was never reopened.

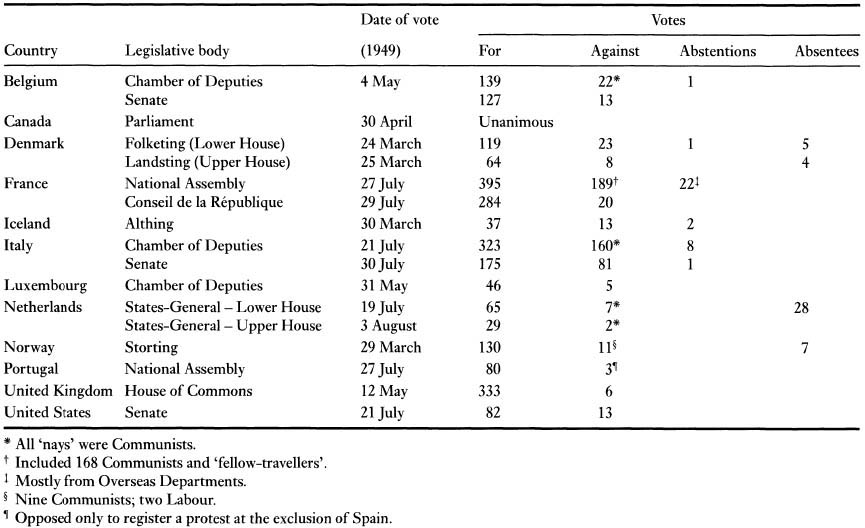

The treaty was signed on 4 April 1949, following which the member countries secured national endorsement, which, as is made clear from

Table 2.1

was obtained by overwhelming majorities, auguring well for the success of the resulting North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

fn2

The armed forces of the twelve NATO powers at the start of the Alliance in 1949 were not impressive, however. The vast American and British wartime fleets had been drastically reduced, with large numbers of ships either scrapped or placed in low-readiness reserve. The air forces numbered less than 1,000 operational aircraft, most of which were obsolete Second World War piston-engined machines, with small numbers of modern jet-engined aircraft concentrated in the British and US air forces. On land there were some twenty nominal divisions, most of which were involved in occupation duties and were poorly equipped and organized for modern war.

Despite these military shortcomings, the Alliance had made a sound start. The Europe of the period was in an extremely agitated state, and both political and military leaders had more than enough problems to deal with, both domestically and, in many cases, abroad. Despite this, the whole process of setting up NATO was achieved with a certainty of common purpose, a deftness of diplomatic and political touch, and a generosity of spirit which can only be viewed with admiration. The speed with which decisions were taken was extraordinary, as was the way in which normal diplomatic procedures were brushed aside in order to achieve results.

Table 2.1

The Voting Record for Ratifying the North Atlantic Treaty

2

fn1

These talks were classified Top Secret, but as a junior British representative was the notorious spy Donald Maclean it seems probable that the Soviet leadership knew as much of what was discussed as did London, Ottawa and Washington.

fn2

The full text of the North Atlantic Treaty is given in

Appendix 2

.

3

The Development of NATO: 1949–1989

THE DIPLOMATIC SCENE

ONCE THE EUPHORIA

resulting from signing the treaty on 4 April 1949 had died down, NATO’s most senior body, the North Atlantic Council, met at foreign-minister level in September and established a number of permanent bodies, including the Defence Council and the Military Committee, as well as regional planning groups to cover the Alliance area. The momentum was maintained by the Defence Council, which in December 1949 agreed to a strategic concept and in the following April to the first draft of a medium-term defence plan.

The invasion of South Korea by the Communist North in June 1950 caused considerable anxiety in western Europe and seemed to prove the case for the existence of the Atlantic Alliance. As a direct result, in September 1950 NATO formally adopted the concept of ‘forward defence’ (i.e. as far to the east as possible) in order to resist similar aggression in Europe. Such a strategy could only be implemented in western Europe by troops stationed in West Germany and, although it had been discussed informally for some time, the question of rearming West Germany was raised formally.

Repeated reorganizations eventually resulted in the appointment of the first Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) in 1950, and of the first Secretary-General, Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) and Commander-in-Chief Channel (CINCHAN) in 1952. That year also saw the first expansion, when Greece and Turkey were brought into the Alliance, thus extending its coverage to include all of the Mediterranean and bringing the Alliance face to face with the USSR on the Soviet–Turkish border. With the inclusion of Turkey, NATO now included an Islamic nation, which was to prove significant in later years, although the traditional hostility between

Greece

and Turkey caused repeated complications, and required a very delicate balance to ensure that neither party felt that the other was being given any form of preferential treatment.

In these first few years the Alliance concentrated on three areas: increasing its defence potential, getting its organization structure right and rearming Germany. The original proposal to solve the ‘German question’ was the creation of a European Defence Community in which West Germany could participate, but this was negated when the French National Assembly voted against such an organization in August 1954. This setback caused a new round of diplomatic activity, which involved both West Germany and Italy joining the Western Union (Brussels Treaty) and was finally resolved in the Paris Agreement of 23 October 1954, under which:

• the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) – West Germany – was declared a sovereign state;

• American, British and French forces in the FRG ceased to be there by right of occupation but remained at the invitation of the government of the FRG;

• the FRG joined NATO;

• the UK and the USA undertook to maintain forces in continental Europe for as long as might be necessary;

• the Western Union was renamed the Western European Union.

The FRG acceded to the NATO alliance on 5 May 1955, and on 14 May the Soviet Union announced the establishment of the Warsaw Pact (

see Chapter 6

). Despite the resulting furore, however, with some treaties being torn up and new ones being signed, the four Second World War allies were still able to sign the Austrian Peace Treaty on 15 May, ending the military occupation of that country.

A Four Power summit was also held in Geneva to discuss a possible peace treaty with Germany, but two sessions – the first in July, the second in October – failed to reach a satisfactory conclusion. The year ended with the Soviet announcement of a policy of ‘peaceful coexistence’, but any optimism generated in NATO was dashed in 1956 by two major events. The joint Anglo-French invasion of Egypt was the first crisis to create serious strains within the Alliance, while the major external event was the Soviet invasion of Hungary, which once again demonstrated the Soviet Union’s determination to maintain its hegemony in eastern Europe. The threat was further enhanced by Soviet progress in the ‘space race’, where a number of successes, such as the launch of the first space satellite in October 1957, showed a capability with major repercussions for the arms race.

In the spring of 1960 the Soviet Union suddenly announced that it had shot down a US ‘spy plane’ on a flight over its territory and had captured the pilot, who had parachuted to safety. US president Dwight D.

Eisenhower

had little alternative but to admit that the USA had been conducting espionage flights, and announced that they had been suspended forthwith, but his Soviet opposite number, First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev, refused to accept this and stormed out of the 16 May Geneva summit conference in protest.

NATO’s momentum increased as members realized that it was a source not only of military but also of political strength. The ‘Athens Guidelines’, issued in 1962, gave a broad outline of the circumstances under which NATO would consider using nuclear weapons and what political discussions might be feasible in a crisis. Later in 1962, however, the Cuban Missile Crisis, when the Soviet Union attempted to place nuclear missiles on the Caribbean island, overshadowed everything that had gone before. The USA and the USSR confronted each other in the western Atlantic. NATO was essentially on the sidelines, although the Alliance issued a formal endorsement of the US actions. One of the outcomes of the Cuban crisis was that in 1963 the USA and the UK assigned some of their existing nuclear forces to NATO, but a related proposal for a NATO-owned and -operated nuclear force came to naught.

In 1963 US president John F. Kennedy paid an extremely successful visit to Europe, which included his famous ‘

Ich bin ein Berliner

’ speech in West Berlin. His assassination later in the year came as a major shock to NATO, although there was muted relief when it became clear that this was not the result of some Soviet plot. Then in 1964 Khrushchev was ousted in a bloodless coup and, on 16 October, China exploded its first atomic bomb.

The year 1966 saw a succession of problems with France culminate in the announcement that French forces would be withdrawn from the integrated command structure (

see Chapter 4

). A corollary was that NATO had to remove all installations not under French command from French soil, which caused a major exodus of headquarters to the Low Countries, and of US military facilities to West Germany and the UK.

In 1967 the Military Committee conducted NATO’s first major strategic review since 1956, proposing a change from the ‘tripwire’ strategy

fn1

to ‘flexible response’ which was approved at a December 1967 ministerial meeting.

fn2

Under this new concept, NATO devized a multitude of balanced responses, both nuclear and conventional, which, in the event of Warsaw Pact aggression, could be implemented in a balanced fashion, depending upon the prevailing circumstances.

1

That year also saw the publication of the ‘Harmel

Report

’ on

Future Tasks of the Alliance

, which restated the principles of the Alliance, stressed the importance of common approaches and greater consultation, and drew ‘particular attention to the defence problems of the exposed areas e.g. the South-Eastern flank’.

2