The Coming of the Third Reich (6 page)

Read The Coming of the Third Reich Online

Authors: Richard J. Evans

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Germany, #World, #Military, #World War II

II

The power of the military and in particular of the Prussian officer corps was not simply the product of times of war. It derived from a long historical tradition. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the expanding Prussian state had organized itself along largely military lines, with the neo-feudal system of landowners - the famous Junkers - and serfs, intermeshing neatly with the military recruiting system for officers and men.

12

This system was dismantled with the ending of serfdom, and the traditional prestige of the army was badly dented by a series of crushing defeats in the Napoleonic wars. In 1848 and again in 1862 Prussian liberals came close to bringing the military under parliamentary control. It was above all in order to protect the autonomy of the Prussian officer corps from liberal interference that Bismarck was appointed in 1862. He immediately announced that ‘the great questions of the day are not decided by speeches and majority resolutions - that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849 - but by iron and blood’.

13

He was as good as his word. The war of 1866 destroyed the Kingdom of Hanover, incorporating it into Prussia, and expelled Austria and Bohemia from Germany after centuries in which they had played a major part in shaping its destinies, while the war of 1870-71 took away Alsace-Lorraine from France and placed it under the direct suzerainty of the German Empire. It is with some justification that Bismarck has been described as a ‘white revolutionary’.

14

Military force and military action created the Reich; and in so doing they swept aside legitimate institutions, redrew state boundaries and overthrew long-established traditions, with a radicalism and a ruthlessness that cast a long shadow over the subsequent development of Germany. They also thereby legitimized the use of force for political ends to a degree well beyond what was common in most other countries except when they contemplated imperial conquests in other parts of the world. Militarism in state and society was to play an important part in undermining German democracy in the 1920s and in the coming of the Third Reich.

Bismarck saw to it that the army was virtually a state within a state, with its own immediate access to the Kaiser and its own system of self-government. The Reichstag only had the right to approve its budget every seven years, and the Minister of War was responsible to the army rather than to the legislature. Officers enjoyed many social and other privileges and expected the deference of civilians when they met on the street. Not surprisingly, it was the ambition of many a bourgeois professional to be admitted as an officer in the army reserve; while, for the masses, compulsory military service produced familiarity with military codes of conduct and military ideals and values.

15

In times of emergency, the army was entitled to establish martial law and suspend civil liberties, a move considered so frequently during the Wilhelmine period that some historians have with pardonable exaggeration described the politicians and legislators of the time as living under the permanent threat of a

coup d’état

from above.

16

The army impacted on society in a variety of ways, most intensively of all in Prussia, then after 1871 more indirectly, through the Prussian example, in other German states as well. Its prestige, gained in the stunning victories of the wars of unification, was enormous. Non-commissioned officers, that is, those men who stayed on after their term of compulsory military service was over and served in the army for a number of years, had an automatic right to a job in state employment when they finally left the army. This meant that the vast majority of policemen, postmen, railwaymen and other lower servants of the state were ex-soldiers, who had been socialized in the army and behaved in the military fashion to which they had become accustomed. The rule-book of an institution like the police force concentrated on enforcing military models of behaviour, insisted that the public be kept at arm’s length and ensured that, in street marches and mass demonstrations, the crowd would be more likely to be treated like an enemy force than an assembly of citizens.

17

Military concepts of honour were pervasive enough to ensure the continued vitality of duelling among civilian men, even amongst the middle classes, though it was also common in Russia and France as well.

18

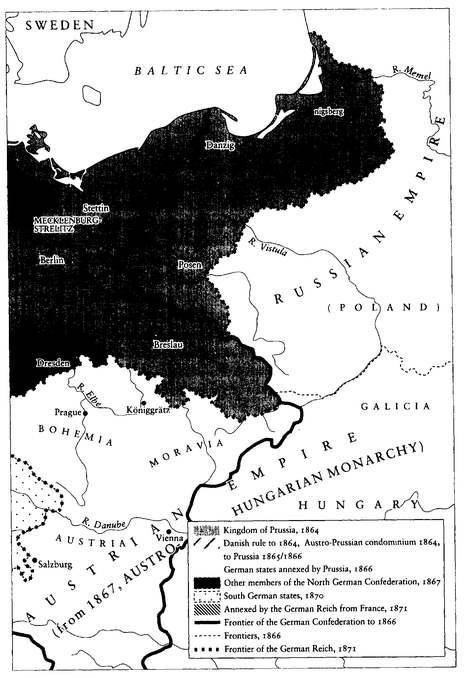

Map

1. The Unification of Germany, 1864-1871

Over time, the identification of the officer corps with the Prussian aristocracy weakened, and aristocratic military codes were augmented by new forms of popular militarism, including in the early 1900s the Navy League and the veterans’ clubs.

19

By the time of the First World War, most of the key positions in the officer corps were held by professionals, and the aristocracy was dominant mainly in traditional areas of social prestige and snobbery such as the cavalry and the guards, much as it was in other countries. But the professionalization of the officer corps, hastened by the advent of new military technology from the machine gun and barbed wire to the aeroplane and the tank, did not make it any more democratic. On the contrary, military arrogance was strengthened by the colonial experience, when German armed forces ruthlessly put down rebellions of indigenous peoples such as the Hereros in German South-West Africa (now Namibia).

20

In 1904-7, in an act of deliberate genocide, the German army massacred thousands of Herero men, women and children and drove many more of them into the desert, where they starved. From a population of some 80,000 before the war, the Hereros declined to a mere 15,000 by 1911 as a result of these actions.

21

In an occupied part of the German Empire such as Alsace-Lorraine, annexed from France in 1871, the army frequently behaved like conquerors facing a hostile and refractory population. Some of the most flagrant examples of such behaviour had given rise in 1913 to a heated debate in the Reichstag, in which the deputies passed a vote of no-confidence in the government. This did not of course force the government to resign, but it illustrated none the less the growing polarization of opinion over the role of the army in German society.

22

The extent to which Bismarck managed to control the army’s wilder impulses and restrain its desire for massive territorial annexations in the wake of its military victories was not realized by many at the time. Indeed, particularly after his enforced resignation in 1890, the myth emerged - encouraged not least by the disgruntled ex-Chancellor and his followers - of Bismarck himself as a charismatic leader who had ruthlessly cut the Gordian knots of politics and solved the great questions of the day by force. It was Bismarck’s revolutionary wars in the 1860S that remained in the German public memory, not the two subsequent decades in which he tried to maintain the peace in Europe in order to allow the German Reich to find its feet. As the diplomat Ulrich von Hassell, a leader of the conservative resistance to Hitler in 1944, confided to his diary during a visit to Bismarck’s old residence at Friedrichsruh:

It is regrettable how false is the picture which we ourselves have created of him in the world, as the jackbooted politician of violence, in childish pleasure at the fact that someone finally brought Germany to a position of influence again. In truth, his great gift was for the highest diplomacy and moderation. He understood uniquely how to win the world’s trust, the exact opposite of today.

23

The myth of the dictatorial leader was not the expression of an ancient, ingrained aspect of the German character; it was a much more recent creation.

It was fuelled in the early twentieth century by the public memory of Bismarck’s tough stance against those whom he regarded as the internal enemies of the Reich. In the 1870s, reacting against the Pope’s attempts to strengthen his hold over the Catholic community through the Syllabus of Errors (1864) and the Declaration of Papal Infallibility (1871), Bismarck inaugurated what liberals dubbed the ‘struggle for culture’, a series of laws and police measures which aimed to bring the Catholic Church under the control of the Prussian state. The Catholic clergy refused to co-operate with laws requiring them to undergo training at state institutions and submit clerical appointments to state approval. Before long, those who contravened the new laws were being hounded by the police, arrested and sent to gaol. By the mid-1870s, 989 parishes were without incumbents, 225 priests were in gaol, all Catholic religious orders apart from those involved in nursing had been suppressed, two archbishops and three bishops had been removed from office and the Bishop of Trier had died shortly after his release from nine months in prison.

24

What was even more disturbing was that this massive assault on the civil liberties of some

40

per cent of the population of the Reich was cheered on by Germany’s liberals, who regarded Catholicism as so serious a threat to civilization that it justified extreme measures such as these.

The struggle eventually died down, leaving the Catholic community an embittered enemy of liberalism and modernity and determined to prove its loyalty to the state, not least through the political party it had formed in order, initially, to defend itself against persecution, the so-called Centre Party. But before this process was even complete, Bismarck struck another blow against civil liberties with the Anti-Socialist Law, passed by the Reichstag after two assassination attempts on the aged Kaiser Wilhelm I in 1878. In fact, Germany’s fledgling socialist movement had nothing to do with the would-be assassins and was a law-abiding organization, putting its trust in the parliamentary route to power. Once more, however, the liberals were persuaded to abandon their liberal principles in what was presented to them as the national interest. Socialist meetings were banned, socialist newspapers and magazines suppressed, the socialist party outlawed. Capital punishment, previously in abeyance in Prussia and every other major German state, was reintroduced. Mass arrests and the widespread imprisonment of socialists followed.

25

The consequences of the Anti-Socialist Law were, if anything, even more far-reaching than those of the struggle with the Catholic Church. It, too, completely failed in its immediate aim of suppressing supposed ‘enemies of the Reich’. The socialists could not legally be banned from standing in parliamentary elections as individuals, and as Germany’s industrialization gathered pace and the industrial working class increased ever more rapidly in numbers, so socialist candidates won an ever-growing share of the vote. After the law was allowed to lapse in 1890, the socialists reorganized themselves in the Social Democratic Party of Germany. By the eve of the First World War the party had over a million members, the largest political organization anywhere in the world. In the 1912 elections, despite an inbuilt bias of the electoral system in favour of conservative rural constituencies, it overtook the Centre Party as the largest single party in the Reichstag. The repression of the Anti-Socialist Law had driven it to the left, and from the beginning of the 1890s onwards it adhered to a rigid Marxist creed according to which the existing institutions of Church, state and society, from the monarchy and the army officer corps to big business and the stock market, would be overthrown in a proletarian revolution that would bring a socialist republic into being. The liberals’ support for the Anti-Socialist Law caused the Social Democrats to distrust all ‘bourgeois’ political parties and to reject any idea of co-operating with the political supporters of capitalism or the exponents of what they regarded as a merely palliative reform of the existing political system.

26

Vast, highly disciplined, tolerating no dissent, and seemingly unstoppable in its forward march towards electoral dominance, the Social Democratic movement struck terror into the hearts of the respectable middle and upper classes. A deep gulf opened up between the Social Democrats on the one hand and all the ’bourgeois’ parties on the other. This unbridgeable political divide was to endure well into the 1920s and play a vital role in the crisis that eventually brought the Nazis to power.

At the same time, however, the party was determined to do everything it could to remain within the law and not to provide any excuse for the oft-threatened reintroduction of a banning order. Lenin was once said to have remarked, in a rare flash of humour, that the German Social Democrats would never launch a successful revolution in Germany because when they came to storm the railway stations they would line up in an orderly queue to buy platform tickets first. The party acquired the habit of waiting for things to happen, rather than acting to bring them about. Its massively elaborate institutional structure, with its cultural organizations, its newspapers and magazines, its pubs, its bars, its sporting clubs and its educational apparatus, came in time to provide a whole way of life for its members and to constitute a set of vested interests that few in the party were prepared to jeopardize. As a law-abiding institution, the party put its faith in the courts to prevent persecution. Yet remaining within the law was not easy, even after 1890. Petty chicanery by the police was backed up by conservative judges and prosecutors, and by courts that continued to regard the Social Democrats as dangerous revolutionaries. There were few Social Democratic speakers or party newspaper editors who had not by 1914 spent several terms of imprisonment after being convicted of

lèse-majesté

or insulting state officials; criticizing the monarch or the police or even the civil servants who ran the country could still count as an offence under the law. Combating the Social Democrats became the business of a whole generation of judges, state prosecutors, police chiefs and government officials before 1914. These men, and the majority of their middle- and upper-class supporters, never accepted the Social Democrats as a legitimate political movement. In their eyes, the law’s purpose was to uphold the existing institutions of state and society, not to act as a neutral referee between opposing political groups.

27