The Complete Yes Minister (14 page)

‘How are you enjoying being in Opposition?’ I asked him jocularly.

Like the good politician he is, he didn’t exactly answer my question. ‘How are you enjoying being in government?’ he replied.

I could see no reason to beat about the bush, and I told him that, quite honestly, I’m not enjoying it as much as I’d expected to.

‘Humphrey got you under control?’ he smiled.

I dodged that one, but said that it’s so very hard to get anything done. He nodded, so I asked him, ‘Did

you

get anything done?’

you

get anything done?’

‘Almost nothing,’ he replied cheerfully. ‘But I didn’t cotton on to his technique till I’d been there over a year – and then of course there was the election.’

It emerged from the conversation that the technique in question was Humphrey’s system for stalling.

According to Tom, it’s in five stages. I made a note during our conversation, for future reference.

Stage One

: Humphrey will say that the administration is in its early months and there’s an awful lot of other things to get on with. (Tom clearly knows his stuff. That is just what Humphrey said to me the day before yesterday.)

: Humphrey will say that the administration is in its early months and there’s an awful lot of other things to get on with. (Tom clearly knows his stuff. That is just what Humphrey said to me the day before yesterday.)

Stage Two

: If I persist past Stage One, he’ll say that he quite appreciates the intention, something certainly ought to be done – but is this the right way to achieve it?

: If I persist past Stage One, he’ll say that he quite appreciates the intention, something certainly ought to be done – but is this the right way to achieve it?

Stage Three

: If I’m still undeterred he will shift his ground from how I do it to

when

I do it, i.e. ‘Minister, this is not the time, for all sorts of reasons.’

: If I’m still undeterred he will shift his ground from how I do it to

when

I do it, i.e. ‘Minister, this is not the time, for all sorts of reasons.’

Stage Four

: Lots of Ministers settle for Stage Three according to Tom. But if not, he will then say that the policy has run into difficulties – technical, political and/or legal. (Legal difficulties are best because they can be made totally incomprehensible and can go on for ever.)

: Lots of Ministers settle for Stage Three according to Tom. But if not, he will then say that the policy has run into difficulties – technical, political and/or legal. (Legal difficulties are best because they can be made totally incomprehensible and can go on for ever.)

Stage Five

: Finally, because the first four stages have taken up to three years, the last stage is to say that ‘we’re getting rather near to the run-up to the next general election – so we can’t be sure of getting the policy through’.

: Finally, because the first four stages have taken up to three years, the last stage is to say that ‘we’re getting rather near to the run-up to the next general election – so we can’t be sure of getting the policy through’.

The stages can be made to last three years because at each stage Sir Humphrey will do absolutely nothing until the Minister chases him. And he assumes, rightly, that the Minister has too much else to do. [

The whole process is called Creative Inertia – Ed

.]

The whole process is called Creative Inertia – Ed

.]

Tom asked me what the policy was that I’m trying to push through. When I told him that I’m trying to make the National Integrated Data Base less of a Big Brother, he roared with laughter.

‘I suppose he’s pretending it’s all new?’

I nodded.

‘Clever old sod,’ said Tom, ‘we spent years on that. We almost had a White Paper ready to bring out, but the election was called. I’ve done it all.’

I could hardly believe my ears. I asked about the administrative problems. Tom said there were none – all solved. And Tom guessed that my enquiries about the past were met with silence – ‘clever bugger, he’s wiped the slate clean’.

Anyway, now I know the five stages, I should be able to deal with Humphrey quite differently. Tom advised me not to let on that we’d had this conversation, because it would spoil the fun. He also warned me of the ‘Three Varieties of Civil Service Silence’, which would be Humphrey’s last resort if completely cornered:

The silence when they do not want to tell you the facts:

Discreet Silence

.

Discreet Silence

.

The silence when they do not intend to take any action:

Stubborn Silence

.

Stubborn Silence

.

The silence when you catch them out and they haven’t a leg to stand on. They imply that they could vindicate themselves completely if only they were free to tell all, but they are too honourable to do so:

Courageous Silence

.

Courageous Silence

.

Finally Tom told me what Humphrey’s next move would be. He asked how many boxes they’d given me for tonight: ‘Three? Four?’

‘Five,’ I admitted, somewhat shamefaced.

‘Five?’ He couldn’t hide his astonishment at how badly I was doing. ‘Have they told you that you needn’t worry too much about the fifth?’ I nodded. ‘Right. Well, I’ll bet you that at the bottom of the fifth box will be a submission explaining why any new moves on the Data Base must be delayed – and if you never find it or read it they’ll do nothing further, and in six months’ time they’ll say they told you all about it.’

There was one more thing I wanted to ask Tom, who really had been extremely kind and helpful. He’s been in office for years, in various government posts. So I said to him: ‘Look Tom, you know all the Civil Service tricks.’

‘Not all,’ he grinned, ‘just a few hundred.’

‘Right,’ I said. ‘Now how do you defeat them? How do you make them do something they do not want to do?’

Tom smiled ruefully, and shook his head. ‘My dear fellow,’ he replied, ‘if I knew that I wouldn’t be in Opposition.’

January 13th

I did my boxes so late last night that I’m writing up yesterday’s discoveries a day late.

Tom had been most helpful to me. When I got home I told Annie all about it over dinner. She couldn’t understand why Tom, as a member of the Opposition, would have been so helpful.

I explained to her that the Opposition aren’t really the opposition. They’re just called the Opposition. But, in fact, they are the opposition in exile. The Civil Service are the opposition in residence.

Then after dinner I did the boxes and sure enough, at the bottom of the fifth box, I found a submission on the Data Base. Not merely at the bottom of the fifth box – to be doubly certain the submission had somehow slipped into the middle of an eighty-page report on Welfare Procedures.

By the way, Tom has also lent me all his private papers on the Data Base, which he kept when he left office. Very useful!

The submission contained the expected delaying phrases: ‘Subject still under discussion . . . programme not finalised . . . nothing precipitate . . . failing instructions to the contrary propose await developments.’

Annie suggested I ring Humphrey and tell him that I disagree. I was reluctant – it was 2 a.m., and he’d be fast asleep.

‘Why should he sleep while you’re working?’ Annie asked me. ‘After all, he’s had you on the run for three months. Now it’s your turn.’

‘I couldn’t possibly do that,’ I said.

Annie looked at me. ‘What’s his number?’ I asked, as I reached for our address book.

Annie added reasonably: ‘After all, if it was in the fifth box you couldn’t have found it any earlier, could you?’

Humphrey answered the phone with a curious sort of grunting noise. I had obviously woken him up. ‘Sorry to ring you so late, you weren’t in the middle of dinner, were you?’

‘No,’ he said, sounding somewhat confused, ‘we had dinner some while ago. What’s the time?’

I told him it was 2 a.m.

‘Good God!’ He sounded as though he’d really woken up now. ‘What’s the crisis?’

‘No crisis. I’m still going through my red boxes and I knew you’d still be hard at it.’

‘Oh yes,’ he said, stifling a yawn. ‘Nose to the grindstone.’

I told him I’d just got to the paper on the Data Base.

‘Oh, you’ve found . . .’ he corrected himself without pausing, ‘you’ve read it.’

I told him that I thought he needed to know, straight away, that I wasn’t happy with it, that I knew he’d be grateful to have a little extra time to work on something else, and that I hoped he didn’t mind my calling him.

‘Always a pleasure to hear from you, Minister,’ he said, and I think he slammed down the phone.

After I rang off I realised I’d forgotten to tell him to come and talk about it before Cabinet tomorrow. I was about to pick up the phone when Annie said: ‘Don’t ring him now.’

I was surprised by this sudden show of kindness and consideration for Sir Humphrey, but I agreed. ‘No, perhaps it is a bit late.’

She smiled. ‘Yes. Just give him another ten minutes.’

January 14th

This morning I made a little more progress in my battle for control over Humphrey and my Department, though the battle is not yet won.

But I had with me my notes from the meeting with Tom Sargent, and – exactly as Tom had predicted – Sir Humphrey put his stalling technique into bat.

‘Humphrey,’ I began, ‘have you drafted the proposed safeguards for the Data Base?’

‘Minister,’ he replied plausibly, ‘I quite appreciate your intention and I fully agree that there is a need for safeguards but I’m wondering if this is the right way to achieve it.’

‘It’s my way,’ I said decisively, and I ticked off the first objection in my little notebook. ‘And that’s my decision.’

Humphrey was surprised that his objection had been brushed aside so early, without protracted discussion – so surprised that he went straight on to his second stage.

‘Even so Minister,’ he said, ‘this is not really the time, for all sorts of reasons.’

I ticked off number two in my notebook, and replied: ‘It is the perfect time – safeguards have to develop parallel with systems, not after them – that’s common sense.’

Humphrey was forced to move on to his third objection. Tom really has analysed his technique well.

‘Unfortunately, Minister,’ said Humphrey doggedly, ‘we have tried this before, but, well . . . we have run into all sorts of difficulties.’

I ticked off number three in my little book. Humphrey had noticed this by now, and tried to look over my shoulder to see what was written there. I held the book away from him.

‘What sort of difficulties?’ I enquired.

‘Technical, for example,’ said Humphrey.

Thanks to a careful study of Tom’s private papers, I had the answer ready. ‘No problem at all,’ I said airily. ‘I’ve been doing some research. We can use the same basic file interrogation programme as the US State Department and the Swedish Ministry of the Interior. No technical problems.’

Sir Humphrey was getting visibly rattled, but he persisted. ‘There are also formidable administrative problems. All departments are affected. An interdepartmental committee will have to be set up . . .’

I interrupted him in mid-sentence. ‘No,’ I said firmly. ‘I think you’ll find, if you look into it, that the existing security procedures are adequate. This can just be an extension. Anything else?’

Humphrey was gazing at me with astonishment. He just couldn’t work out how I was so thoroughly in command of the situation. Was I just making a series of inspired guesses, he wondered. As he didn’t speak for a moment, I decided to help him out.

‘Legal problems?’ I suggested helpfully.

‘Yes Minister,’ he agreed at once, hoping that he had me cornered at last. Legal problems were always his best bet.

‘Good, good,’ I said, and ticked off the last but one stage on my little list. Again he tried to see what I had written down.

‘There is a question,’ he began carefully, ‘of whether we have the legal power . . .’

‘I’ll answer it,’ I announced grandly. ‘We have.’ He was looking at me in wonderment. ‘All personnel affected are bound by their service agreement anyway.’

He couldn’t argue because, of course, I was right. Grasping at straws he said: ‘But Minister, there will have to be extra staffing – are you sure you will get it through Cabinet and the Parliamentary Party?’

‘Quite sure,’ I said. ‘Anything else?’ I looked at my list. ‘No, nothing else. Right, so we go ahead?’

Humphrey was silent. I wondered whether he was being discreet, stubborn or courageous. Stubborn, I think.

Eventually,

I

spoke. ‘You’re very silent,’ I remarked. There was more silence. ‘Why are you so silent, by the way?’

I

spoke. ‘You’re very silent,’ I remarked. There was more silence. ‘Why are you so silent, by the way?’

He realised that he had to speak, or the jig was up. ‘Minister, you do not seem to realise how much work is involved.’

Casually, I enquired if he’d never investigated safeguards before, under another government perhaps, as I thought I remembered written answers to Parliamentary questions in the past.

His reply went rather as follows: ‘Minister, in the first place, we’ve agreed that the question is not cricket. In the second place, if there had been investigations, which there haven’t or not necessarily, or I am not at liberty to say if there have, there would have been a project team which, had it existed, on which I cannot comment, would now be disbanded if it had existed and the members returned to their original departments, had there indeed been any such members.’ Or words to that effect.

I waited till the torrent of useless language came to a halt, and then I delivered my ultimatum. I told him that I wanted safeguards on the use of the Data Base made available immediately. He told me it isn’t possible. I told him it is. He told me it isn’t. I told him it is. We went on like that (’tis, ’tisn’t, ’tis, ’tisn’t) like a couple of three-year-olds, glowering at each other, till Bernard popped in.

I didn’t want to reveal that Tom had told me of the safeguards that were ready and waiting, because then I’d have no more aces up my sleeve.

While I contemplated this knotty problem, Bernard reminded me of my engagements: Cabinet at 10, a speech to the Anglo-American Society lunch, and the

World in Focus

interview this evening. I asked him if he could get me out of the lunch. ‘Not really, Minister,’ he answered, ‘it’s been announced. It’s in the programme.’

World in Focus

interview this evening. I asked him if he could get me out of the lunch. ‘Not really, Minister,’ he answered, ‘it’s been announced. It’s in the programme.’

And suddenly the penny dropped. The most wonderful plan formed in my mind, the idea of the century!

I told Humphrey and Bernard to be sure to watch me on TV tonight.

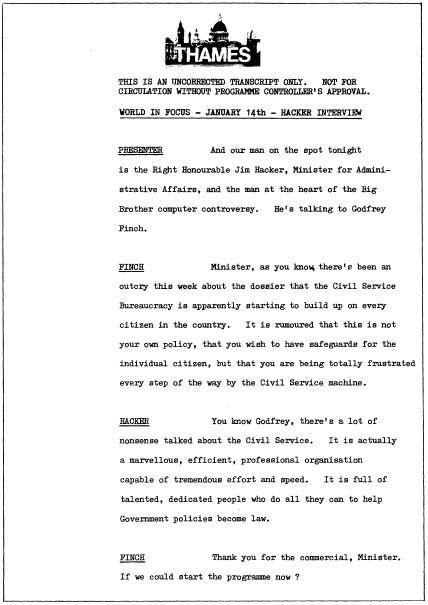

[

The transcript of Hacker’s appearance that night on World in Focus follows. It contains his first truly memorable victory over his officials – Ed

.]

The transcript of Hacker’s appearance that night on World in Focus follows. It contains his first truly memorable victory over his officials – Ed

.]

Other books

Stealing Light by Gary Gibson

The Spellmans Strike Again by Lisa Lutz

The Hunt for the Missing Spy by Penny Warner

Gourdfellas by Bruce, Maggie

Broken Trail by Jean Rae Baxter

THE DODGE CITY MASSACRE (A Jess Williams Novel.) by Thomas, Robert J.

Austerity Britain, 1945–51 by Kynaston, David

Rocky Mountain Haven by Arend, Vivian

Bearly Interested by Kim Fox

The Love Story (The Things We Can't Change Book 4) by Kassandra Kush