The Complete Yes Minister (53 page)

Humphrey seemed upset that I’d accused him of delaying tactics. ‘Minister, you do me an injustice,’ he complained. ‘I was not about to suggest delaying tactics.’

Perhaps I had done him an injustice. I apologised, and waited to see what he

was

about to suggest.

was

about to suggest.

‘I was merely going to suggest,’ he murmured in a slightly hurt tone, ‘that if we are to have a twenty-five per cent quota of women we must have a much larger intake at the recruitment stage. So that eventually we’ll have twenty-five per cent in the top jobs.’

‘When?’ I asked.

I knew the answer before he said it. ‘In twenty-five years.’

‘No, Humphrey,’ I said, still smiling and patient. ‘I don’t think you’ve quite got my drift. I’m talking about

now

.’

now

.’

At last Sir Humphrey got the point. ‘Oh,’ he said, staggered. ‘You mean –

now

!’

now

!’

‘Got it in one, Humphrey,’ I replied with my most patronising smile.

‘But Minister,’ he smiled smoothly, ‘it takes time to do things now.’ And he smiled patronisingly back at me. It’s amazing how quickly he recovers his poise.

I’ve been hearing that kind of stuff for nearly a year now. It no longer cuts any ice with me. ‘Ah yes,’ I said, ‘the three articles of Civil Service faith: it takes longer to do things quickly, it’s more expensive to do things cheaply, and it’s more democratic to do things secretly. No Humphrey, I’ve suggested four years. That’s masses of time.’

He shook his head sadly. ‘Dear me no, Minister, I don’t mean political time, I mean

real

time.’ He sat comfortably back in his chair, gazed at the ceiling, and then continued in a leisurely sort of way. ‘Civil servants are grown like oak trees, not mustard and cress. They bloom and ripen with the seasons.’ I’d never heard such pretentious crap. But he was in full flow. ‘They mature like . . .’

real

time.’ He sat comfortably back in his chair, gazed at the ceiling, and then continued in a leisurely sort of way. ‘Civil servants are grown like oak trees, not mustard and cress. They bloom and ripen with the seasons.’ I’d never heard such pretentious crap. But he was in full flow. ‘They mature like . . .’

‘Like you?’ I interrupted facetiously.

‘I was going to say,’ he replied tartly, ‘that they mature like an old port.’

‘Grimsby, perhaps?’

He smiled a tiny humourless smile. ‘I

am

being serious, Minister.’

am

being serious, Minister.’

He certainly was. Apart from being entirely serious about his own importance, he was seriously trying to use all this flimflam to get me to lose track of my new proposal – or, as I think of it, my new policy decision. I decided to go straight for the jugular.

‘I foresaw this problem,’ I said firmly. ‘So I propose that we solve it by bringing in top women from outside the Service to fill vacancies in the top grades.’

Humphrey’s face was a picture. He was absolutely aghast. The colour drained out of his face.

‘Minister . . . I don’t think I quite . . .’ His voice petered out as he reached the word ‘understood’.

I was enjoying myself hugely.

‘Watch my lips move,’ I said helpfully, and pointed to my mouth with my forefinger. ‘We . . . will . . . bring . . . women . . . in . . . from . . . out- . . . side!’ I said it very slowly and carefully, like a deranged speech therapist. He just sat there and stared at me, transfixed, a rabbit with a snake.

Finally he pulled himself together.

‘But,’ he began, ‘the whole strength of our system is that it is incorruptible, pure, unsullied by outside influences.’

I just can’t see the sense in that old chestnut and I said so. ‘People move from one job to another throughout industry, Humphrey – why should the Civil Service be different?’

‘It

is

different. The Civil Service demands subtlety . . .’

is

different. The Civil Service demands subtlety . . .’

‘Discretion,’ said Bernard.

‘Devotion to duty,’ said Humphrey.

‘Soundness!’ said Bernard.

‘

Soundness

!’ repeated Sir Humphrey emphatically. ‘Well said, Bernard.

Soundness

.’ Bernard had clearly hit upon one of the key compliments in the Civil Service vocabulary.

Soundness

!’ repeated Sir Humphrey emphatically. ‘Well said, Bernard.

Soundness

.’ Bernard had clearly hit upon one of the key compliments in the Civil Service vocabulary.

[

Bernard Woolley, of course, had an important vested interest in this conversation. If Hacker’s policy of bringing women in from outside were implemented, this might well have an adverse effect on the promotion prospects of more junior civil servants such as Woolley. And if women could be brought in to fill top jobs from outside, so could men. What, then, would Bernard Woolley’s prospects have been? – Ed

.]

Bernard Woolley, of course, had an important vested interest in this conversation. If Hacker’s policy of bringing women in from outside were implemented, this might well have an adverse effect on the promotion prospects of more junior civil servants such as Woolley. And if women could be brought in to fill top jobs from outside, so could men. What, then, would Bernard Woolley’s prospects have been? – Ed

.]

Sir Humphrey went on to explain that civil servants require endless patience and boundless understanding, they need to be able to change horses midstream, constantly, as the politicians change their minds. Perhaps it was my imagination, but it seemed to me that he was putting the word ‘minds’ in quotes – as if to imply, ‘as politicians change what they are pleased to call their minds’.

I asked him if he had all these talents. With a modest shrug he replied: ‘Well, it’s just that one has been properly . . .’

‘Matured,’ I interjected. ‘Like Grimsby.’

‘Trained.’ He corrected me with a tight-lipped smile.

‘Humphrey,’ I said, ‘ask yourself honestly if the system is not at fault.

Why

are there so few women Deputy Secretaries?’

Why

are there so few women Deputy Secretaries?’

‘They keep leaving,’ he explained, with an air of sweet reason, ‘to have babies. And things.’

This struck me as a particularly preposterous explanation, ‘Leaving to have babies? At the age of nearly fifty? Surely not!’

But Sir Humphrey appeared to believe it. Desperately he absolved himself of all responsibility or knowledge. ‘Really Minister, I don’t know. Really I don’t. I’m on your side. We do indeed need more women at the top.’

‘Good,’ I replied decisively, ‘because I’m not waiting twenty-five years. We’ve got a vacancy for a Deputy Secretary here, haven’t we?’

He was instantly on his guard. He even thought cautiously for a moment before replying.

‘Yes.’

‘Very well. We shall appoint a woman. Sarah Harrison.’

Again he was astounded, or aghast, or appalled. Something like that. Definitely not pleased, anyway. But he contented himself with merely repeating her name, in a quiet controlled voice.

‘Sarah Harrison?’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I think she’s very able. Don’t you?’

‘Very able, for a woman. For a person.’ He had corrected himself with scarcely a hesitation.

‘And,’ I added, ‘she has ideas. She’s an original thinker.’

‘I’m afraid that’s true,’ agreed Sir Humphrey, ‘but she doesn’t let it interfere with her work.’

So I asked him what he had against her. He insisted that he had

nothing

against her, that he was totally

pro

her. He confirmed that she is an excellent worker, and he pointed out that he is a great supporter of hers and had in fact advocated her promotion to Under-Secretary only last year at a very early age.

nothing

against her, that he was totally

pro

her. He confirmed that she is an excellent worker, and he pointed out that he is a great supporter of hers and had in fact advocated her promotion to Under-Secretary only last year at a very early age.

‘Would you say she is an outstanding Under-Secretary?’ I asked him.

‘Yes,’ he replied, without equivocation.

‘So,’ I said, ‘on balance it’s a good idea, isn’t it?’

‘On balance? Yes . . . and no.’

I told him that that was not a clear answer. He said it was a balanced answer. Touché. Then he went on to explain that the point is, in his opinion, that she’s too young and it’s not her turn yet.

I leaped upon that argument. I’d been expecting it. ‘That is precisely what’s

wrong

with the Civil Service – Buggins’ Turn! Whereas the best people should be promoted, as soon as possible.’

wrong

with the Civil Service – Buggins’ Turn! Whereas the best people should be promoted, as soon as possible.’

‘Exactly,’ agreed Sir Humphrey, ‘as soon as it’s their turn.’

‘Rubbish. Napoleon ruled Europe in his thirties. Alexander the Great conquered the world in his twenties.’

‘They would have made

very

poor Deputy Secretaries,’ remarked Sir Humphrey contemptuously.

very

poor Deputy Secretaries,’ remarked Sir Humphrey contemptuously.

‘At least they didn’t wait their turn,’ I pointed out.

‘And look what happened to them.’ Sir Humphrey clearly thought he’d won our little debate. So I decided to make the argument rather more personal.

‘Look what’s happened to

us

,’ I said calmly. ‘Instead of this country being run by bright energetic youthful brains it is being run by tired routine-bound fifty-five-year-olds who just want a quiet life.’

us

,’ I said calmly. ‘Instead of this country being run by bright energetic youthful brains it is being run by tired routine-bound fifty-five-year-olds who just want a quiet life.’

Humphrey stared at me coldly. ‘Had you anyone specific in mind, Minister?’

I smiled. ‘Yes . . . and no, Humphrey.’ Game, set and match to yours truly, I felt.

Sir Humphrey decided to move the debate back to the specific problem. He informed me, in his most matter-of-fact fashion, that Sarah Harrison is an excellent civil servant and a bright hope for the future. But he also reiterated that she is our most junior Under-Secretary and that he cannot and will not recommend her for promotion.

There was a clear implication in that final comment that it was ultimately up to him, and that I should mind my own business.

I told him he was a sexist.

I’m surprised he didn’t laugh at me. Surprisingly, this trendy insult seemed to cut him to the quick. He was outraged.

‘Minister,’ he complained bitterly, ‘how can you say such a thing? I’m very pro-women. Wonderful people, women. And Sarah Harrison is a dear lady. I’m one of her most ardent admirers. But the fact is that if the cause of women is to be advanced it must be done with tact and care and discretion. She is our only woman contender for a top job. We mustn’t push her too fast. Women find top jobs very difficult, you know.’

He

is

a sexist.

is

a sexist.

‘Can you hear yourself?’ I asked incredulously.

Unabashed, he continued in the same vein. ‘If women were able to be good Permanent Secretaries, there would be more of them, wouldn’t there? Stands to reason.’

I’ve never before heard a reply that so totally begs the question.

‘No Humphrey!’ I began, wondering where to begin.

But on he went. ‘I’m no anti-feminist. I love women. Some of my best friends are women. My wife, indeed.’ Methinks Sir Humphrey doth protest too much. And on and on he went. ‘Sarah Harrison is not very experienced, Minister, and her two children are still of school age, they might get mumps.’

Another daft argument. Anybody can be temporarily off work through their own ill-health, not just their children’s. ‘You might get shingles, Humphrey, if it comes to that,’ I said.

He missed my point. ‘I might indeed, Minister, if you continue in this vein,’ he muttered balefully. ‘But what if her children caused her to miss work all the time?’

I asked him frankly if this were likely. I asked if she were likely to have reached the rank of Under-Secretary if her children kept having mumps. I pointed out that she was the best person for the job.

He didn’t disagree about that. But he gave me an indignant warning: ‘Minister, if you go around promoting women just because they’re the best person for the job, you could create a lot of resentment throughout the whole Civil Service.’

‘But not from the women in it,’ I pointed out.

‘Ah,’ said Sir Humphrey complacently, ‘but there are so few of them that it wouldn’t matter so much.’

A completely circular argument. Perhaps this is what is meant by moving in Civil Service circles.

[

Later in the week Sir Humphrey Appleby had lunch with Sir Arnold Robinson, the Cabinet Secretary, at the Athenaeum Club. Sir Humphrey, as always, made a note on one of his pieces of memo paper – Ed

.]

Later in the week Sir Humphrey Appleby had lunch with Sir Arnold Robinson, the Cabinet Secretary, at the Athenaeum Club. Sir Humphrey, as always, made a note on one of his pieces of memo paper – Ed

.]

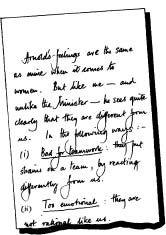

Arnold’s feelings are the same as mine when it comes to women. But like me – and unlike the Minister – he sees quite clearly that they are different from us. In the following ways:-

Bad for teamwork:

they put strains on a team, by reacting differently from us.

they put strains on a team, by reacting differently from us.

Too emotional:

they are not rational like us.

they are not rational like us.

Can’t be Reprimanded:

they either get into a frightful bate or start blubbing.

they either get into a frightful bate or start blubbing.

Can be Reprimanded:

some of them can be, but are frightfully hard and butch and not in the least bit attractive.

some of them can be, but are frightfully hard and butch and not in the least bit attractive.

Prejudices:

they are full of them.

they are full of them.

Silly Generalisations:

they make them.

they make them.

Stereotypes:

they think in them.

they think in them.

I asked Arnold for his advice. Arnold suggested that I lecture the Minister at such length on the matter that he becomes bored and loses interest in the whole idea.

There is a remote chahce of success for such a plan. But Hacker does not get bored easily. He even finds

himself

interesting. They all do in fact. All the ones who listen to what they’re saying of course. On second thoughts, that is by no means all of them.

himself

interesting. They all do in fact. All the ones who listen to what they’re saying of course. On second thoughts, that is by no means all of them.

But the fact remains that Hacker’s boredom threshold is high. He even reads most of the stuff that we put into his red boxes, with apparent interest!

Arnold also suggested that standard second ploy: to tell the Minister that the Unions won’t wear it. [‘

It’ being the importation of women into the Service to fill some top jobs – Ed

.] We agreed that this was a line of action worth pursuing.

It’ being the importation of women into the Service to fill some top jobs – Ed

.] We agreed that this was a line of action worth pursuing.

We also discussed the feminine angle. His wife [

the Minister’s, that is – Ed

.] is in favour of promoting the Harrison female, and may well – from what I know of Mrs Hacker – be behind all this. However, she may not know that Harrison is extremely attractive. I’m sure Mrs H. and Mrs H. have never met. This could well be fruitful.

the Minister’s, that is – Ed

.] is in favour of promoting the Harrison female, and may well – from what I know of Mrs Hacker – be behind all this. However, she may not know that Harrison is extremely attractive. I’m sure Mrs H. and Mrs H. have never met. This could well be fruitful.

Other books

The Mammoth Book of Unsolved Crimes by Wilkes, Roger

End Game by Waltz, Vanessa

Sex, Lies, and Headlocks by Shaun Assael

Set in Stone by Linda Newbery

A Tale Of Three Lions by H. Rider Haggard

After the Lockout by Darran McCann

Voodoo Tales: The Ghost Stories of Henry S Whitehead (Tales of Mystery & The Supernatural) by Henry S. Whitehead, David Stuart Davies

Ronicky Doone (1921) by Brand, Max

Mercy by Dimon, HelenKay

The Truth of All Things by Kieran Shields