The Cost of Courage (14 page)

Read The Cost of Courage Online

Authors: Charles Kaiser

Most of them are younger than thirty-five. The youngest prisoner is fifteen, the oldest, seventy-one. They range from laborers and journalists to businessmen, politicians, and policemen.

Among the more famous are Pierre Johnson, inspector general of Compagnie Transatlantique shipping company, who is a great-great-nephew of the nineteenth-century American president Andrew Johnson, and Count Paul Chandon-Möet, a champagne magnate, who will die a few days before his prison camp is liberated by the Allies.

Also on board is Charles Porte. Porte was the police commissioner of Chartres when Jean Moulin, the head of the Resistance, was prefect of Eure-et-Loir. Porte had been responsible for security for the inaugural meeting of the Conseil national de la Résistance, which Moulin presided over on May 27, 1943. Porte will survive deportation and return to France after the war.

During four horrific days and three terrible nights, the prisoners struggle to survive without food or water. Dozens of them succumb before the train reaches the death camp. The cars are so crammed with humanity, no one ever has enough room to sit down. André is guarded the whole time by Gilbert Farges and Rémy, both of whom are big enough to protect him; fortunately, Farges is as wide as he is tall. André’s organs are kept inside by a very thin layer of skin, and a blow to his stomach would surely be fatal.

When thirst and hunger take hold, many of the prisoners become delirious, touching off terrifying scenes of madness. “As time passed, the temperature mounted, asphyxiation was winning, and a devouring thirst installed itself with dementia and violence,” Farges remembered.

As one prisoner after another dies, their corpses are piled on top of one another in a corner to make more room for the survivors. “The crazy people become dangerous to the point where they try to open their own veins or those of others to drink their blood.”

Rémy tells Farges, “We will not let your friend André die because of these maniacs.” Somehow, through it all, André retains a strong spirit. “That was essential,” said Farges. Occasionally, André is able to snatch a breath of fresh air from the cracks in the car. Just once, the Germans offer a bucket of water, but the prisoners are so frantic that it gets turned over before anyone can take a drink.

As their journey approaches the end, the survivors are nearly naked after stripping themselves because of the scorching heat. As the train reaches Silesia, the temperature drops, and the fetid air inside becomes slightly fresher. By the time they reach Auschwitz, it is freezing, and the ground is covered with snow.

When the doors of the cars are finally flung open, the prisoners are greeted by Gestapo men armed with revolvers and machine guns, others with vicious dogs pulling at their leashes, and the notorious capos, prisoners who are violent criminals used by the Germans to assist them with their punishments.

As he climbs out of the train, one of the Frenchmen jumps on a guard, causing his gun to misfire; the man is immediately shot dead by another German.

The prisoners are put in two separate barracks in Birkenau, the main extermination camp at Auschwitz. There each one is tattooed with a number on his forearm. Finally, the day after their arrival, they are given their first drink of water in five days.

After that, under the watchful eyes of the capos — “precarious survivors, brutal, hostile thieves who also know fear in this atmosphere of death” — all of the hair on their bodies is shaved.

Auschwitz is an unusual destination for these political prisoners: The convoy of April 27 is one of only three trains of non-Jews to be sent there from France during the entire war. André believed that these seventeen hundred prisoners were brought to Auschwitz to be exterminated in retaliation for the death of Pierre Pucheu. A former minister of the interior in the collaborationist Vichy government, he had been executed by the Free French in Algiers one month earlier.

The personal intervention of Marshal Pétain may be the only reason that everyone on the train isn’t executed immediately.

DETERMINATION

,

DIGNITY

,

AND LUCK

are the three requirements for survival. Remarkably, those are the attributes André still has in abundance. “After three weeks of murderous drills, the survivors still hadn’t given up,” Gilbert Farges recalled. The fearful scene reminded him of a saying of Montaigne: “They bent their knees, but held their souls high.”

The prisoners watch the smoke spewing from the chimneys of the crematoria of Auschwitz all day and all night. After a few weeks, the survivors of the first convoy are put onto a new train of cattle cars, this one destined for Buchenwald. The transfer means a

tiny improvement in André’s chances for survival. Ninety-five percent of the deportees to Auschwitz died at that camp, compared to 85 percent of the inmates at Buchenwald.

The capos at Auschwitz tell them their new home will be practically a “sanitarium” compared to their present one.

*

An ironic choice for Vernier-Palliez: Four decades later he will become France’s ambassador to the United States.

†

Neither man can imagine that one year from now, Rondenay will succeed André as de Gaulle’s military delegate in Paris, after André is arrested.

‡

André’s brother-in-law, Alex Katlama, told his son, Michel, that André hadn’t been tortured because he had been wounded: “My father told me that they didn’t torture him because they were worried he would die, or he wouldn’t be able to take it.” (author’s interview with Michel Katlama, March 14, 1999)

Of course the two years through which Free France had endured had also been filled with reversals and disappointments, but then we had to stake everything to win everything; we had felt ourselves surrounded by a heroic atmosphere, sustained by the necessity of gaining our ends at any price.

— Charles de Gaulle

B

ACK IN PARIS

, Christiane and Jacqueline have finally moved out of their parents’ home into a new secret apartment. Apparently, it doesn’t occur to anyone that Jacques, or André, might have been tortured into giving up their parents’ address. In any case, their father never considers resigning his job as the director of the bureau of highways or going into hiding with his wife. His main concern, Christiane believes, is to keep his country working, “for the French.”

As James L. Stokesbury observed, men like Christiane’s father “were servants of the state, sworn to defend it; the accidents of war had made the legitimate French government a tool of the conqueror, yet it was still the official French government. It took a special kind of person to throw aside the norms of a lifetime, to make the lonely decision that there was a higher loyalty, a higher duty, than that he had always acknowledged, and in the name of some abstract moral principle to work against his own government.”

Robert Paxton, the preeminent American historian of Vichy France, points out that “as the state came under challenge by Resistance vigilantism, a commitment to the ongoing functioning of the state reinforced the weight of routine … Resistance was not merely personally perilous. It was also a step toward social revolution.”

After André Boulloche’s arrest in January 1944, de Gaulle replaces him as military delegate in Paris with André Rondenay, André’s college classmate, whom he had run into in Spain a year earlier, when Boulloche was on his way to London.

Rondenay is a man of parts. His thick brown hair and horn-rim glasses give him the look of an intellectual, and he favors three-piece suits with double-breasted vests.

Three and a half years into the war, Rondenay is a famous escape artist. First taken prisoner in the Vosges region of France near the German border in June 1940, he spends time as a prisoner in Saarburg and Westphalia before being transferred to Mainz in October.

After escaping and being recaptured several times, he is taken to Colditz Castle, a prisoner-of-war camp for officers, in January 1942. In May, he is moved again, this time to Lübeck.

*

There he manages to manufacture the perfect papers of a German officer. On December 19, 1942, he and a comrade walk out unchallenged through the front gate of the camp.

His fake identity continues to protect him during an incredible journey through Hamburg, Frankfurt, Mayence, Ludwigshafen, and Strasbourg. After a brief stay in France, he crosses the Spanish frontier on January 23, 1943.

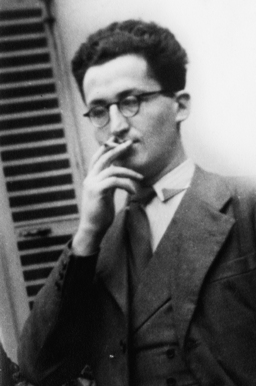

André Rondenay was a master forger and a famous escape artist. When he became Christiane’s boss in the Resistance in 1944, she was mesmerized by him.(

photo credit 1.12

)

Arrested by the Spanish police, he is interned at Pamplona, where he runs into his old classmate André Boulloche, who had arrived in Spain four weeks before him.

Managing to fabricate the fake papers of a German officer for himself and a comrade named Noël Palaud, Rondenay escapes yet again with Palaud and a third conspirator. Within a few weeks, they reach Portugal, and Rondenay finally makes it to England on April 4, 1943.

IN THE FACE

of mounting danger in the spring of 1944, Rondenay remains surprisingly cheerful. His fearlessness is lightened by an infectious sense of humor and a beguiling ability to make fun of himself. To boost Christiane’s spirits, he writes a song that makes fun of her youth and the fact that she has never told

her parents exactly what she is doing. And he continues to concoct everything from a train ticket to a German officer’s identity card at a moment’s notice. His wife, Solange, is one of his deputies.

Christiane knows Rondenay as “Jarry” — the latest of his many wartime aliases. The others are Lemniscate, Sapeur, Jean-Louis Lebel, and Francis Courtois. He gives Christiane “very large sums” of money, which arrive from London, and she distributes it to their confederates. “I was twenty,” she said. “It was completely crazy. He had total confidence in me. I think he had more confidence in me than he did in himself.”

Now Monsieur and Madame Rondenay are living with the Boulloche girls, plus Georges, another force of nature, who has escaped Germany three times. This motley crew is rounded out by their radio operator, Riquet, and his wife, Gaby. All of them live together in the same apartment, in total secrecy.

CHRISTIANE

had become a student at Sciences Po in the fall of 1941, and André told her to continue to show up there occasionally, after she went to work for him in the fall of 1943. She also continued to live with her parents. Only after André’s arrest does she stop going to school and move out of her parents’ apartment, to begin a completely clandestine life.

One part of Christiane’s job is to take care of Riquet’s radio equipment. His transmissions are in constant danger of being discovered by the Gestapo, which deploys “gonios” — trucks equipped with homing devices to locate the secret transmitters.

To reduce the chances of being discovered, they never transmit from the same location for very long. At one point, Christiane’s aunt, Françoise Farcot, allows her niece to use her modest country house to make a few broadcasts. One day, when Christiane isn’t there, the Gestapo arrives at her aunt’s house.

Seeing them at the front door, one of Christiane’s cousins snatches the radio and manages to hide it in the attic. If he hadn’t been so quick, everyone in the house would have been arrested.

Even as a teenager, Christiane is already a person of tremendous self-control. One night in Paris, she is in a secret apartment with four confederates, waiting for an important phone call. One of her comrades, a boy who has just been parachuted in from England, soothes his nerves by downing one cognac after another. Christiane is quietly disdainful. She thinks to herself,

At least I am courageous

—

even though I am a girl!

When the phone finally rings, they are all ordered outside. Christiane is carrying their radio equipment. Suddenly her suitcase bursts open, and all of the electronic contraband spills out into the street. Christiane scrambles to put everything back, then disappears into the night as quickly as possible.

Christiane is also responsible for coding and decoding the telegrams that go to and from London. It is exacting work, and her least favorite task. Sometimes she delivers weapons to assist in sabotage missions. Whenever possible, London prefers to get things blown up in France on the ground, rather than bombed from the air, because it reduces the chances of civilian casualties.

†

She continues to follow all the rudimentary rules of spy craft that the British have taught her brother. She particularly loves the “Métro trick”: In the first car there is a conductor who controls the doors. “You put yourself in the first car, close to the conductor. The Métro stops, and you don’t move. And then when you see he is about to push the button to close the doors, you jump out. Then you can’t be followed.”

She always chooses a secret apartment with two exits, and she never waits more than ten minutes for someone to show up for a rendezvous. She trains herself to be suspicious of everyone, all the time: That is the hardest part of her job.