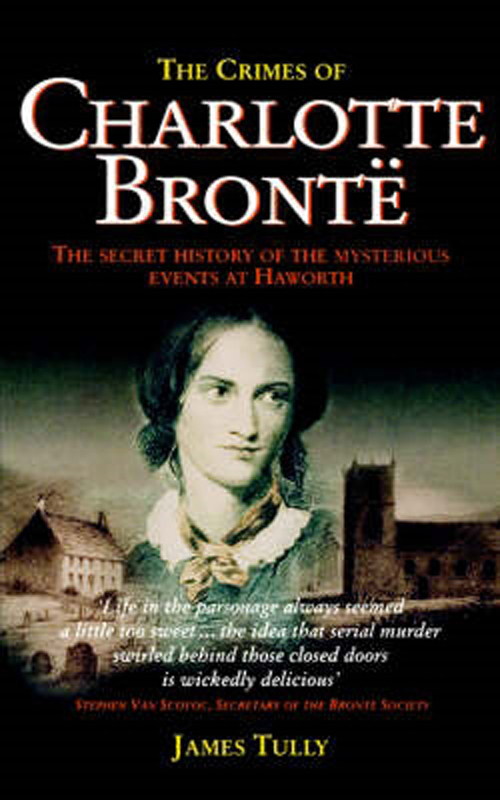

The Crimes of Charlotte Bronte

Read The Crimes of Charlotte Bronte Online

Authors: James Tully

CHARLOTTE BRONTÃ

CHARLOTTE BRONTÃ

The secret history of the mysterious events at Haworth

James Tully

Robinson

LONDON

Para mi querida J . . . â whom I met when she was but seventeen and have loved deeply for some fifty years

Â

Â

Â

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55â56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Robinson Publishing Ltd 1999

This paperback edition 1999

Copyright © James Tully 1999

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN 1-84119-131-0

eISBN: 978-1-47211-199-9

Printed and bound in the EC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3

Cover copyright © Constable & Robinson

M

y name is Charles Coutts, and I am a partner in the firm of solicitors Coutts, Heppelthwaite and Larkin, which was established in 1788 by my great-great-great-great-grandfather, Henry Coutts.

Henry began his practice from one room which he rented in a large four-storied building in Keighley, Yorkshire. He prospered, and, over the centuries, more and more rooms were acquired until, in 1926, my grandfather bought the freehold of the entire property. Then, three years ago, we received an offer for it which we could not refuse.

Some developers were willing to pay a considerable sum in order that they might demolish the building and then use the entire, very large, site for the construction of a shopping mall. Actually we were, in effect, made two offers. We could either have the total amount in cash, or have our pick, at a favourable price, of a spacious suite of offices in a new block which was nearing completion, and receive the balance.

I discussed the matter with the other partners at some length, and in the end we realized that we should be foolish not to jump at the proposal. Our premises needed a lot spending on them, and they were already costing the earth to heat and maintain. It was a heaven-sent opportunity to cut our losses and move, and that was just what we did â after opting for the âpart-exchange' deal.

As we had anticipated, the changeover was a major upheaval. To move one's home is bad enough, but to clear such a large building of all the junk which had accumulated in over two centuries was a nightmare. It had been decided that it would be best if we dealt with the removal floor by floor, and transferred to our new offices gradually. We began, therefore, with the two large attics.

Many years had slipped away since I was last up there â as a small boy during the Second World War â and, remembering what it was like then, it was with some trepidation that I ascended the rickety stairs to make an inspection.

What I beheld, when I finally managed to force open the first door, confirmed my memories â and my worst fears. The rooms were packed from floorboards to rafters. It seemed that my forebears had been unable to throw away anything whatsoever, and it was going to be a task of gargantuan proportions to sort through what was there.

I undertook the supervision of the work myself, mainly because I did not wish anything of value to be discarded, but also because I was interested in my ancestry and the history of the firm. In other words, as I overheard one of my partners say, I was âboth acquisitive and inquisitive'!

It was a slow business but, with the help of four stalwart workmen, I was able to make steady and rewarding progress. A couple of containers of rubbish went off to the tip, but there were many other items, some genuine antiques, which we sold at prices which astounded us.

There was, however, one piece of furniture which I earmarked for myself. It was a handsome George IV bureau/bookcase, which I thought would stand nicely in my study. I gave it a rough wipe with a rag, made sure that it was free from woodworm, and then had it taken to my home where it was stored, temporarily, in the garage.

What with the move, and other matters, it was some weeks before I was able to get round to a closer inspection. Eventually, however, a weekend arrived when I had the time to give it a good cleaning in order to see whether any restoration would be necessary.

I lowered the flap which formed the writing-top, and then removed all the drawers before starting work. It appeared to be in good condition, and I was feeling quite pleased with myself as I beavered away with cloth and polish. Then, suddenly, as I was rubbing the side of the large central section, there was a loud âclick' and, to my utter amazement, the bottom of the section swung up.

What was revealed was one of those secret compartments so beloved by nineteenth-century craftsmen. The base of the middle section was false, and obviously I had touched something which released what was, in fact, a carefully hinged lid to the hiding-place below.

Among other bits and pieces, it contained various documents which, I was to discover, had been placed there by my great-great-grandfather who died, suddenly and quite unexpectedly, in 1878. All had been of a highly confidential nature at the time, but most were now no longer so and need not concern us here. However, the contents of a brown paper parcel have intrigued me ever since I read them, and have given me many a sleepless night.

The parcel measured some twelve inches by ten, and was about three inches thick. It was sealed with red wax, imprinted upon which was the name of our firm, and tied neatly with white tape, the knot of which was also sealed and bore the signet of my ancestor James Coutts. On the front of the parcel, in his magnificent copperplate handwriting, were the words: âStatement sworn to by Miss Martha Brown of Bell Cottage, Stubbing Lane, Haworth, on January 8th, 1878. Not to be opened until after her death, and that of Arthur Bell Nicholls, Esquire, of Hill House, Banagher, King's County, Ireland.'

It was the stuff of which murder mysteries are made and, never having seen similar phraseology before in my professional career, my curiosity knew no bounds. I was filled with anticipation as â oh, so carefully â I slit open the parcel and examined the contents.

They consisted of a pile of rather tattered old school exercise books, one of which, I found later, had been used as something of a diary by Anne Brontë.

At the end of the final paragraph, on the last page of the books, there was a deposition that what had been written in the books was true. That was followed by a form of wording which authorized James Coutts or his successors to use the information contained in the books in any way they saw fit, but only after the deaths of the signatory and Mr Nicholls. Below that, and witnessed by James Coutts and one of his clerks, was the signature âMartha Brown', written in a good hand for one who, I was to discover, had been a mere servant woman.

I had to read the books several times before I had a proper appreciation of the enormities which they detailed. Apparently Martha Brown had been a servant in the employ of the legendary Brontë family of Haworth â which is some five miles from Keighley as the crow flies. Among other things, she claimed that most of the Brontë family had been murdered, and that she was privy to one of the killings. What she alleged she had witnessed made startling reading, especially as part of it was self-incriminatory, but, if it was all true, I understood why she had seen fit to have her testimony signed and sealed.

Was

it true, though? Or

could

it be true? Although their former home was so close to mine, I must confess that I knew very little about the Brontës. I had once accompanied my wife, under sufferance, to Haworth and the Parsonage â but had thought the best part of the trip was our visit to the Black Bull afterwards! From holidays in Cornwall, I also knew the house in Penzance in which Mrs Brontë had lived until she married. That, however, was the sum total of my knowledge of the family. As for the literary works of the three daughters, I had heard of

Jane Eyre

and

Wuthering Heights

but had never read them.

What Martha Brown deposed was to alter all that. Clearly I needed to check on all the available evidence. I wanted to know why she had chosen James Coutts' firm, and whether what she had told him was in keeping with the known facts about the Brontës.

The answer to my first query was easily discovered. I found that our firm had acted for the Haworth Church Trustees on many occasions, a fact of which Martha might have been aware both from working at the Parsonage and being the daughter of the sexton at Haworth. It was logical, therefore, that she should have come to us, and the senior partner would have been the only person to whom she would have imparted such extraordinary information.

As for my other question, I began on the premise that James Coutts must have thought that there was at least

some

truth in what she had confided. Otherwise, from what I had read of him, he would probably have sent her packing with a stern warning ringing in her ears. I then embarked upon what was to become a lengthy process of research, but it did not take all that long to come to the conclusion that there was something seriously amiss with the generally accepted legend of the Brontë family.

It all seemed far too good to be true. Three almost saint-like sisters â Charlotte, Emily and Anne â live with their stern, but equally saint-like, father in a grim parsonage in a wild part of England. After very little formal schooling, and not until they are all far into their twenties, each writes â in the very same year â a romantic novel which sells well. Within ten years they are all dead, but they live on in their books â which continue to sell well nearly 150 years after the last sister's death.

Interwoven with their lives is a young and handsome curate who arrives, very coincidentally, at the start of the year in which the novels are written. He eventually marries the eldest sister who dies, tragically, whilst carrying their first child. Husband, heartbroken at the loss of his one true love, vows that he will care for her aged father for the rest of his life. This he does, for six long years, until the venerable, white-haired patriarch finally departs to meet his Maker.

The sad and lonely widower then rides off into the sunset to try to find some meaning in Life. Curtain down; not a dry eye in the house.

Of course, being Victorian, the story has to paint a moral, and this is provided appropriately by the sisters' brother, Branwell Brontë. He is intelligent, artistically gifted, and shows great promise. However, he falls in with bad companions and is easily led into a life of debauchery. Inevitably he comes to a sad, but only to be expected, end through his addiction to drink, drugs and gambling. Let that be a lesson to us all, and an encouragement to sign the Pledge before it is too late!

I fear that, according to Martha Brown, the reality was very different. The Brontës were

all

fallible, and subject to short-comings as are we all.

Having checked her story, and what Anne Brontë had written, against the known facts, I was in a dilemma. I had been able to discover nothing which contradicted what she had to say. Initially I had made my enquiries merely to satisfy my own curiosity; but now that I had done so, and become convinced of the veracity of the documents, what should my next step be?

Probably the easiest thing would have been to have destroyed the books, or at least kept the whole matter to myself. Nobody would have been any the wiser, and the âauthorized version' of the Brontë legend would have continued to be accepted. On balance, however, and only after a great deal of thought, I decided that the statement and the âdiary' were historical documents which should be made public.