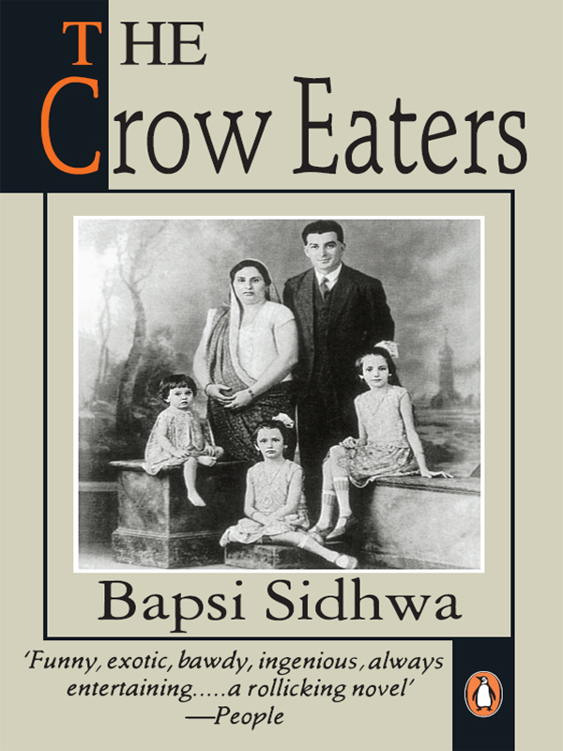

The Crow Eaters

Authors: Bapsi Sidhwa

The Crow Eaters

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Bapsi Sidhwa was born in Karachi and brought up in Lahore. In addition to

The Crow Eaters,

her first published novel, she has published two other critically acclaimed novels

The Pakistani Bride

and

Ice-Candy-Man.

An active social worker she represented Pakistan at the 1975 Asian Women’s Congress. Bapsi Sidhwa is married, with three children, and lives in Lahore.

This book is dedicated

to my parents

Tehmina & Peshotan Bhandara

FAREDOON Junglewalla, Freddy for short, was a strikingly handsome, dulcet-voiced adventurer with so few scruples that he not only succeeded in carving a comfortable niche in the world for himself but he also earned the respect and gratitude of his entire community. When he died at sixty-five, a majestic grey-haired patriarch, he attained the rare distinction of being locally listed in the ‘Zarathusti Calendar of Great Men and Women’.

At important Parsi ceremonies, like thanksgivings and death anniversaries, names of the great departed are invoked with gratitude – they include the names of ancient Persian kings and saints, and all those who have served the community since the Parsis migrated to India.

Faredoon Junglewalla’s name is invoked in all major ceremonies performed in the Punjab and Sind – an ever-present testimony to the success of his charming rascality.

In his prosperous middle years Faredoon Junglewalla was prone to reminiscence and rhetoric. Sunk in a cane-backed easy-chair after an exacting day, his long legs propped up on the sliding arms of the chair, he talked to the young people gathered at his feet:

‘My children, do you know what the sweetest thing in this world is?’

‘No, no, no.’ Raising a benign hand to silence an avalanche of suggestions, he smiled and shook his head. ‘No, it is not sugar, not money – not even mother’s love!’

His seven children, and the young visitors of the evening,

leaned forward with popping eyes and intent faces. His rich deep voice had a cadence that lilted pleasurably in their ears.

‘The sweetest thing in the world is your

need

. Yes, think on it. Your own

need

– the mainspring of your wants, well-being and contentment.’

As he continued, the words ‘need’ and ‘wants’ edged over their common boundaries and spread to encompass vast new horizons, flooding their minds with his vision.

‘Need makes a flatterer of a bully and persuades a cruel man to kindness. Call it circumstances – call it self-interest – call it what you will, it still remains your need. All the good in this world comes from serving our own ends. What makes you tolerate someone you’d rather spit in the eye? What subdues that great big “I”, that monstrous ego in a person? Need, I tell you – will force you to love your enemy as a brother!’

Billy devoured each word. A callow-faced stripling with a straggling five-haired moustache, he believed his father’s utterances to be superior even to the wisdom of Zarathustra.

The young men loved best of all those occasions when there were no women around to cramp Faredoon’s style. At such times Freddy would enchant them with his candour. One evening when the women were busy preparing dinner, he confided in them.

‘Yes, I’ve been all things to all people in my time. There was that bumptious son-of-a-bitch in Peshawar called Colonel Williams. I cooed to him – salaamed so low I got a crick in my balls — buttered and marmaladed him until he was eating out of my hand. Within a year I was handling all traffic of goods between Peshawar and Afghanistan!

‘And once you have the means, there is no end to the good you can do. I donated towards the construction of an orphanage and a hospital. I installed a water pump with a stone plaque dedicating it to my friend, Mr Charles P. Allen. He had just arrived from Wales, and held a junior position in the Indian Civil Service; a position that was strategic to my business. He was a pukka sahib then – couldn’t stand the

heat. But he was better off than his memsahib! All covered with prickly heat, the poor skinny creature scratched herself raw.

‘One day Allen confessed he couldn’t get his prick up. “On account of this bloody heat,” he said. He was an obliging bastard, so I helped him. First I packed his wife off to the hills to relieve her of her prickly heat. Then I rallied around with a bunch of buxom dancing-girls and Dimple Scotch. In no time at all he was cured of his distressing symptoms!

‘Oh yes, there is no end to the good one can do.’ Here, to his credit, the red-blooded sage winked circumspectly. Faredoon’s vernacular was interspersed with laboured snatches of English spoken in a droll intent accent.

‘Ah, my sweet little innocents,’ he went on, ‘I have never permitted pride and arrogance to stand in my way. Where would I be had I made a delicate flower of my pride – and sat my delicate bum on it? I followed the dictates of my needs, my wants – they make one flexible, elastic, humble. “The meek shall inherit the earth,” says Christ. There is a lot in what he says. There is also a lot of depth in the man who says, “Sway with the breeze, bend with the winds,”’ he orated, misquoting authoritatively.

‘There are hardly a hundred and twenty thousand Parsis in the world – and still we maintain our identity – why? Booted out of Persia at the time of the Arab invasion 1,300 years ago, a handful of our ancestors fled to India with their sacred fires. Here they were granted sanctuary by the prince Yadav Rana on condition that they did not eat beef, wear rawhide sandals or convert the susceptible masses. Our ancestors weren’t too proud to bow to his will. To this day we do not allow conversion to our faith – or mixed marriages.

‘I’ve made friends – love them – for what could be called “ulterior motives,” and yet the friendships so made are amongst my sweetest, longest and most sincere. I cherish them still.’

He paused, sighing, and out of the blue, suddenly he said: ‘Now your grandmother – bless her shrewish little heart –

you have no idea how difficult she was. What lengths I’ve had to go to; what she has exacted of me! I was always good to her though, for the sake of peace in this house. But for me, she would have eaten you out of house and home!

‘Ah, well, you look after your needs and God looks after you …’

His mellifluous tone was so reasonable, so devoid of vanity, that his listeners felt they were the privileged recipients of a revelation. They burst into laughter at this earthier expatiation and Faredoon (by this time even his wife had stopped calling him Freddy) exulted at the rapport.

‘And where, if I may ask, does the sun rise?

‘No, not in the East. For us it rises – and sets – in the Englishman’s arse. They are our sovereigns! Where do you think we’d be if we did not curry favour? Next to the nawabs, rajas and princelings, we are the greatest toadies of the British Empire! These are not ugly words, mind you. They are the sweet dictates of our delicious need to exist, to live and prosper in peace. Otherwise, where would we Parsis be? Cleaning out gutters with the untouchables – a dispersed pinch of snuff sneezed from the heterogeneous nostrils of India! Oh yes, in looking after our interests we have maintained our strength – the strength to advance the grand cosmic plan of Ahura Mazda – the deep spiritual law which governs the universe, the path of

Asha

.’

How they loved him. Faces gleaming, mouths agape, they devoutly soaked up the eloquence and counsel of their middle-aged guru. But for all his wisdom, all his glib talk, there was one adversary he could never vanquish.

Faredoon Junglewalla, Freddy for short, embarked on his travels towards the end of the nineteenth century. Twenty-three years old, strong and pioneering, he saw no future for himself in his ancestral village, tucked away in the forests of Central India, and resolved to seek his fortune in the hallowed pastures of the Punjab. Of the sixteen lands created by Ahura

Mazda, and mentioned in the 4,000-year-old Vendidad, one is the ‘Septa Sindhu’; the Sind and Punjab of today.

Loading his belongings, which included a widowed mother-in-law eleven years older than himself, a pregnant wife six years younger, and his infant daughter, Hutoxi, on to a bullock-cart, he set off for the North.

The cart was a wooden platform on wheels — fifteen feet long and ten feet across. Almost two-thirds of the platform was covered by a bamboo and canvas structure within which the family slept and lived. The rear of the cart was stacked with their belongings.

The bullocks stuck to the edge of the road and progressed with a minimum of guidance. Occasionally, having spent the day in town, they travelled at night. The beasts would follow the road hour upon hour while the family slept soundly through until dawn.

Added to the ordinary worries and cares of a long journey undertaken by bullock-cart, Freddy soon found himself confronted by two serious problems. One was occasioned by the ungentlemanly behaviour of a very resolute rooster; the other by the truculence of his indolent mother-in-law.

Freddy’s wife, Putli, taking steps to ensure a daily supply of fresh eggs, had hoisted a chicken coop on to the cart at the very last moment. The bamboo coop contained three plump, low-bellied hens and a virile cock.

Freddy’s objection to their presence had been overruled.

Freddy gently governed and completely controlled his wife with the aid of three maxims. If she did or wanted to do something that he considered intolerable and disastrous, he would take a stern and unshakeable stand. Putli soon learnt to recognise and respect his decisions on such occasions. If she did, or planned something he considered stupid and wasteful, but not really harmful, he would voice his objections and immediately humour her with his benevolent sanction. In all other matters she had a free hand.

He put the decision to cart the chickens into the second

category and after launching a mild protest, graciously acceded to her wish.

The rooster was her favourite. A handsome, long-legged creature with a majestic red comb and flashy up-curled tail, he hated being cooped up with the hens in the rear of the cart. At dawn he awoke the household with shrill, shattering crows that did not cease until Putli let the birds out of their coop. The cock would then flutter his iridescent feathers, obligingly service his harem, and scamper to the very front of the cart. Here he spent the day strutting back and forth on the narrow strip that served as a yard, or stood at his favourite post on the right-hand shaft like a sentinel. At crowded junctions he preened his navy-blue, maroon and amber feathers, and crowed lustily for the benefit of admiring onlookers. Putli spoilt him with scraps of left-over food and chapati crumbs.

Quite hysterical at the outset of the expedition the cock had, in a matter of days, grown to love the ride. The monotonous, creaking rhythm of their progress through dusty roads filled him with delight and each bump or untoward movement thrilled his responsive and joyous little heart. He never left the precincts of the cart. Once in a while, seized by a craving for adventure, he would flap across the bullocks and juggling his long black legs dexterously, alight on their horns. Good naturedly, Freddy shooed him back to his quarters.

Freddy’s troubles with the rooster began a fortnight after the start of their journey.

Freddy had already devised means to overcome the hurdles impeding his love life. Every other evening he would chance upon a scenic haven along the route, and raving about the beauty of a canal bank, or a breeze-bowed field of mustard, propel his mother-in-law into the wilderness. Jerbanoo, barely concealing her apathy, allowed herself to be parked on a mat spread out by her son-in-law. Sitting down by her side he would point out landmarks or comment on the serenity of the landscape. A few moments later, reddening under her resigned and knowing look, he would offer some lame excuse

and leave her to partake of the scene alone. Freddy would then race back to the cart, pull the canvas flaps close and fling himself into the welcoming arms of his impatient wife.

One momentous evening the rooster happened to chance into the shelter. Cocking his head to one side, he observed Freddy’s curious exertions with interest. Combining a shrewd sense of timing with humour, he suddenly hopped up and with a minimum of flap or fuss planted himself firmly upon Freddy’s amorous buttocks. Nothing could distract Freddy at that moment. Deep in his passion, subconsciously thinking the pressure was from his wife’s rapturous fingers, Freddy gave the cock the ride of his life. Eyes asparkle, wings stretched out for balance, the cock held on to his rocking perch like an experienced rodeo rider.

It was only after Freddy sagged into a sated stupor, nerves uncurled with langour, that the cock, raising both his tail and his neck, crowed, ‘Coo-ka-roo-coooo!’

Freddy reacted as if a nuclear device had been set off in his ears. He sprang upright, and the surprised Putli sat up just in time to glimpse the nervous rooster scurry out between the flaps.

Putli doubled over with laughter; a phenomenon so rare that Freddy, overcoming his murderous wrath, subsided at her feet with a sheepish grin.

Freddy took the precaution of tying the flaps securely and all went well the next few times. But the rooster, having tasted the cup of joy, was eager for another sip.

Some days later he discovered a rent in the canvas at the back of the shack. Poking his neck in he observed the tumult on the mattress. His inquisitive little eyes lit up and his comb grew rigid. Timing his moves with magnificent judgment he slipped in quietly and rode the last thirty seconds in a triumphant orgy of quivering feathers. This time Freddy was dimly conscious of the presence on his bare behind, but impaled by his mounting, obliviating desires there was nothing he could do.

His body relaxed, unwinding helplessly, and the cock

crowed into his ears. Freddy leapt up. Had Putli not restrained him he would have wrung the fowl’s neck there and then.

When the whole performance was repeated a week later, Freddy knew something would have to be done – and quickly. Afraid to shock his wife, he awaited his chance which came in the guise of a water buffalo that almost gored his mother-in-law.

At dawn they had stopped on the outskirts of a village. Jerbanoo, obedient to the call of nature, was wading into a field of maize with an earthenware mug full of toilet water, when out from behind a haystack appeared a buffalo. He stood still, his great black head and red eyes looking at her across the green expanse of maize.

Jerbanoo froze in the knee-high verdure. The domestic buffalo is normally very docile, but this one was mean. She could tell by the defiant tilt of his head and by the intense glow in his fierce eyes. Cautiously bending her knees, Jerbanoo attempted to hide among the stalks, but the buffalo, with a downward toss of the head, began his charge.