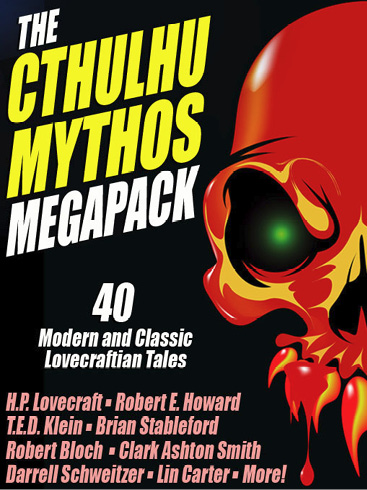

The Cthulhu Mythos Megapack (40 Modern and Classic Lovecraftian Tales)

Read The Cthulhu Mythos Megapack (40 Modern and Classic Lovecraftian Tales) Online

Authors: Anthology

Tags: #Horror, #Supernatural, #Cthulhu, #Mythos, #Lovecraft

THE CTHULHU MYTHOS MEGAPACK

40 CLASSIC AND MODERN LOVECRAFTIAN STORIES

EDITED BY

JOHN GREGORY BETANCOURT

AND COLIN AZARIAH-KRIBBS

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

The Cthulhu Megapack

is copyright © 2012 by Wildside Press LLC. All rights reserved.

* * * *

“At the Mountains of Madness,” by H. P. Lovecraft, originally appeared as a three-part serial in

Astounding Stories

(February-April 1936).

“The Events at Poroth Farm,” by T.E.D. Klein, originally appeared in

From Beyond the Dark Gateway

#2, December 1972. Reprinted by permission of the author. This version has been revised especially for this edition and is copyright © 2012 by T.E.D. Klein.

“The Return of the Sorcerer, by Clark Ashton Smith, originally appeared in

Wonder Stories

, March 1933.

“Worms of the Earth,” by Robert E. Howard, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, November 1932.

“Envy, the Gardens of Ynath, and the Sin of Cain,” by Darrell Schweitzer, originally appeared in

Interzone

, April 2002. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Drawn from Life,” by John Glasby, is copyright © 2012 by the Estate of John Glasby. This is its first publication in this form. Published by permission of the Cosmos Literary Agency.

“In the Haunted Darkness,” by Michael R. Collings, is copyright © 2012 by Michael R. Collings. Published by permission of the author.

“The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” by H. P. Lovecraft, originally appeared as a book in 1936 from the Visionary Publishing Company.

“The Innsmouth Heritage,” by Brian Stableford, originally appeared as a chapbook from Necronomicon Press. Copyright © 1992 by Brian Stableford.

“The Doom That Came to Innsmouth,” by Brian McNaughton, originally appeared in

Tales Out of Innsmouth

. Revised edition appeared in

Even More Nasty Stories

(Wildside Press). Copyright © 1999, 2000 by Brian McNaughton. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Nameless Offspring,” by Clark Ashton Smith, originally appeared in

The Magazine of Horror

#33 (1932).

“The Hounds of Tindalos,” by Frank Belknap Long, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, March 1939.

“The Faceless God,” by Robert Bloch, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, May 1936.

“The Children of Burma,” by Stephen Mark Rainey, originally appeared in

The Spook

#1, July 2001. Copyright © 2001 by Stephen Mark Rainey. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Call of Cthulhu,” by H.P. Lovecraft, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, February 1928.

“The Old One,” by John Glasby, is copyright © 2012 by the Estate of John Glasby. This is its first publication in this form. Published by permission of the Cosmos Literary Agency.

“The Holiness of Azédarac,” by Clark Ashton Smith, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, November 1933.

“Those of the Air,” by Darrell Schweitzer and Jason Van Hollander, originally appeared in

Cthulhu’s Heirs

. Copyright © 1992 by Darrell Schweitzer and Jason Van Hollander. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“The Graveyard Rats,” by Henry Kuttner, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, March 1936.

“Toadface,” by Mark McLaughlin, originally appeared in

Motivational Shrieker

. Copyright © 2004 by Mark McLaughlin. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Whisperer in Darkness,” by H. P. Lovecraft, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, August 1931.

“The Eater of Hours,” by Darrell Schweitzer, originally appeared in

Inhuman

#4, copyright © 2009 by Darrell Schweitzer. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Ubbo-Sathla,” by Clark Ashton Smith, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, July 1933.

“The Space-Eaters,” by Frank Belknap Long, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, July 1928.

“The Fire of Asshurbanipal,” by Robert E. Howard, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, December 1936.

“Beyond the Wall of Sleep,” by H.P. Lovecraft, originally appeared in

Pine Cones

, October 1919.

“Something in the Moonlight,” by Lin Carter, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

#2, copyright © 1980 by Lin Carter. Reprinted by permission of Lin Carter Properties.

“The Salem Horror,” by Henry Kuttner, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, May 1937.

“The Colour Out of Space,” by H. P. Lovecraft, originally appeared in

Amazing Stories

, September 1927.

“Down in Limbo,” by Robert M. Price, originally appeared in

Deathrealm

#24, copyright © 1995 by Robert M. Price. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Dweller in the Gulf,” by Clark Ashton Smith, originally appeared in

The Abominations of Yondo

(1960).

“Azathoth,” by H.P. Lovecraft, originally appeared in

Leaves

(1938).

“Pickman’s Modem,” by Lawrence Watt-Evans, originally appeared in

Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine

, February 1992. Copyright © 1992 by Lawrence Watt-Evans. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“The Hunters from Beyond,” by Clark Ashton Smith, originally appeared in

Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror

, Oct 1932.

“Ghoulmaster,” by Brian McNaughton, originally appeared in

Miskatonic University

. A revised version appeared in

Even More Nasty Stories

(Wildside Press). Copyright © 1996, 2000 by Brian McNaughton. Reprinted by permission of Wildside Press LLC.

“The Spawn of Dagon,” by Henry Kuttner, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, July

1938.

“Dark Destroyer,” by Adrian Cole, originally appeared in

Swords Against the Millenium

and is copyright © 2000 by Adrian Cole. Reprinted by permission of the author. Published by permission of the Cosmos Literary Agency.

“The Dunwich Horror,” by H. P. Lovecraft, originally appeared in

Weird Tales

, April 1929.

“The Dark Boatman” is copyright © 2012 by the Estate of John Glasby. This is its first publication in this form.

“Dagon and Jill,” by John P. McCann, originally appeared in

Necrotic Tissue

#13. Copyright © 2011 by John P. McCann. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Cover art © 2012 by Fotolia.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

At the Mountains of Madness by H. P. Lovecraft

The Events at Poroth Farm by T.E.D. Klein

The Return of the Sorcerer by Clark Ashton Smith

Worms of the Earth by Robert E. Howard

Envy, the Gardens of Ynath, and the Sin of Cain by Darrell Schweitzer

Drawn from Life by John Glasby

In the Haunted Darkness by Michael R. Collings

The Shadow Over Innsmouth by H. P. Lovecraft

The Innsmouth Heritage by Brian Stableford

The Doom That Came to Innsmouth by Brian McNaughton

The Nameless Offspring by Clark Ashton Smith

The Hounds of Tindalos by Frank Belknap Long

The Faceless God by Robert Bloch

The Children of Burma by Stephen Mark Rainey

The Call of Cthulhu by H.P. Lovecraft

The Holiness of Azédarac by Clark Ashton Smith

Those of the Air by Darrell Schweitzer and Jason Van Hollander

The Graveyard Rats by Henry Kuttner

The Whisperer in Darkness by H. P. Lovecraft

The Eater of Hours by Darrell Schweitzer

Ubbo-Sathla by Clark Ashton Smith

The Space-Eaters by Frank Belknap Long

The Fire of Asshurbanipal by Robert E. Howard

Beyond the Wall of Sleep by H.P. Lovecraft

Something in the Moonlight by Lin Carter

The Salem Horror by Henry Kuttner

The Colour Out of Space by H. P. Lovecraft

Down in Limbo by Robert M. Price

The Dweller in the Gulf by Clark Ashton Smith

Pickman’s Modem by Lawrence Watt-Evans

The Hunters from Beyond by Clark Ashton Smith

Ghoulmaster by Brian McNaughton

The Spawn of Dagon by Henry Kuttner

The Dunwich Horror by H. P. Lovecraft

The Dark Boatman by John Glasby

Dagon and Jill by John P. McCann

AT THE MOUNTAINS OF MADNESS (Part 1), by H. P. Lovecraft

I

I am forced into speech because men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why. It is altogether against my will that I tell my reasons for opposing this contemplated invasion of the Antarctic—with its vast fossil hunt and its wholesale boring and melting of the ancient ice caps. And I am the more reluctant because my warning may be in vain.

Doubt of the real facts, as I must reveal them, is inevitable; yet, if I suppressed what will seem extravagant and incredible, there would be nothing left. The hitherto withheld photographs, both ordinary and aerial, will count in my favor, for they are damnably vivid and graphic. Still, they will be doubted because of the great lengths to which clever fakery can be carried. The ink drawings, of course, will be jeered at as obvious impostures, notwithstanding a strangeness of technique which art experts ought to remark and puzzle over.

In the end I must rely on the judgment and standing of the few scientific leaders who have, on the one hand, sufficient independence of thought to weigh my data on its own hideously convincing merits or in the light of certain primordial and highly baffling myth cycles; and on the other hand, sufficient influence to deter the exploring world in general from any rash and over-ambitious program in the region of those mountains of madness. It is an unfortunate fact that relatively obscure men like myself and my associates, connected only with a small university, have little chance of making an impression where matters of a wildly bizarre or highly controversial nature are concerned.

It is further against us that we are not, in the strictest sense, specialists in the fields which came primarily to be concerned. As a geologist, my object in leading the Miskatonic University Expedition was wholly that of securing deep-level specimens of rock and soil from various parts of the Antarctic continent, aided by the remarkable drill devised by Professor Frank H. Pabodie of our engineering department. I had no wish to be a pioneer in any other field than this, but I did hope that the use of this new mechanical appliance at different points along previously explored paths would bring to light materials of a sort hitherto unreached by the ordinary methods of collection.

Pabodie’s drilling apparatus, as the public already knows from our reports, was unique and radical in its lightness, portability, and capacity to combine the ordinary artesian drill principle with the principle of the small circular rock drill in such a way as to cope quickly with strata of varying hardness. Steel head, jointed rods, gasoline motor, collapsible wooden derrick, dynamiting paraphernalia, cording, rubbish-removal auger, and sectional piping for bores five inches wide and up to one thousand feet deep all formed, with needed accessories, no greater load than three seven-dog sledges could carry. This was made possible by the clever aluminum alloy of which most of the metal objects were fashioned. Four large Dornier aeroplanes, designed especially for the tremendous altitude flying necessary on the Antarctic plateau and with added fuel-warming and quick-starting devices worked out by Pabodie, could transport our entire expedition from a base at the edge of the great ice barrier to various suitable inland points, and from these points a sufficient quota of dogs would serve us.

We planned to cover as great an area as one Antarctic season—or longer, if absolutely necessary—would permit, operating mostly in the mountain ranges and on the plateau south of Ross Sea; regions explored in varying degree by Shackleton, Amundsen, Scott, and Byrd. With frequent changes of camp, made by aeroplane and involving distances great enough to be of geological significance, we expected to unearth a quite unprecedented amount of material—especially in the pre-Cambrian strata of which so narrow a range of Antarctic specimens had previously been secured. We wished also to obtain as great as possible a variety of the upper fossiliferous rocks, since the primal life history of this bleak realm of ice and death is of the highest importance to our knowledge of the earth’s past. That the Antarctic continent was once temperate and even tropical, with a teeming vegetable and animal life of which the lichens, marine fauna, arachnida, and penguins of the northern edge are the only survivals, is a matter of common information; and we hoped to expand that information in variety, accuracy, and detail. When a simple boring revealed fossiliferous signs, we would enlarge the aperture by blasting, in order to get specimens of suitable size and condition.

Our borings, of varying depth according to the promise held out by the upper soil or rock, were to be confined to exposed, or nearly exposed, land surfaces—these inevitably being slopes and ridges because of the mile or two-mile thickness of solid ice overlying the lower levels. We could not afford to waste drilling the depth of any considerable amount of mere glaciation, though Pabodie had worked out a plan for sinking copper electrodes in thick clusters of borings and melting off limited areas of ice with current from a gasoline-driven dynamo. It is this plan—which we could not put into effect except experimentally on an expedition such as ours—that the coming Starkweather-Moore Expedition proposes to follow, despite the warnings I have issued since our return from the Antarctic.

The public knows of the Miskatonic Expedition through our frequent wireless reports to the

Arkham Advertiser

and Associated Press, and through the later articles of Pabodie and myself. We consisted of four men from the University—Pabodie, Lake of the biology department, Atwood of the physics department—also a meteorologist—and myself, representing geology and having nominal command—besides sixteen assistants: seven graduate students from Miskatonic and nine skilled mechanics. Of these sixteen, twelve were qualified aeroplane pilots, all but two of whom were competent wireless operators. Eight of them understood navigation with compass and sextant, as did Pabodie, Atwood, and I. In addition, of course, our two ships—wooden ex-whalers, reinforced for ice conditions and having auxiliary steam—were fully manned.

The Nathaniel Derby Pickman Foundation, aided by a few special contributions, financed the expedition; hence our preparations were extremely thorough, despite the absence of great publicity. The dogs, sledges, machines, camp materials, and unassembled parts of our five planes were delivered in Boston, and there our ships were loaded. We were marvelously well-equipped for our specific purposes, and in all matters pertaining to supplies, regimen, transportation, and camp construction we profited by the excellent example of our many recent and exceptionally brilliant predecessors. It was the unusual number and fame of these predecessors which made our own expedition—ample though it was—so little noticed by the world at large.

As the newspapers told, we sailed from Boston Harbor on September 2nd, 1930, taking a leisurely course down the coast and through the Panama Canal, and stopping at Samoa and Hobart, Tasmania, at which latter place we took on final supplies. None of our exploring party had ever been in the polar regions before, hence we all relied greatly on our ship captains—J. B. Douglas, commanding the brig

Arkham

, and serving as commander of the sea party, and Georg Thorfinnssen, commanding the barque

Miskatonic

—both veteran whalers in Antarctic waters.

As we left the inhabited world behind, the sun sank lower and lower in the north, and stayed longer and longer above the horizon each day. At about 62° South Latitude we sighted our first icebergs—tablelike objects with vertical sides—and just before reaching the Antarctic circle, which we crossed on October 20th with appropriately quaint ceremonies, we were considerably troubled with field ice. The falling temperature bothered me considerably after our long voyage through the tropics, but I tried to brace up for the worse rigors to come. On many occasions the curious atmospheric effects enchanted me vastly; these including a strikingly vivid mirage—the first I had ever seen—in which distant bergs became the battlements of unimaginable cosmic castles.

Pushing through the ice, which was fortunately neither extensive nor thickly packed, we regained open water at South Latitude 67°, East Longitude 175°. On the morning of October 26th a strong land blink appeared on the south, and before noon we all felt a thrill of excitement at beholding a vast, lofty, and snow-clad mountain chain which opened out and covered the whole vista ahead. At last we had encountered an outpost of the great unknown continent and its cryptic world of frozen death. These peaks were obviously the Admiralty Range discovered by Ross, and it would now be our task to round Cape Adare and sail down the east coast of Victoria Land to our contemplated base on the shore of McMurdo Sound, at the foot of the volcano Erebus in South Latitude 77° 9’.

The last lap of the voyage was vivid and fancy-stirring. Great barren peaks of mystery loomed up constantly against the west as the low northern sun of noon or the still lower horizon-grazing southern sun of midnight poured its hazy reddish rays over the white snow, bluish ice and water lanes, and black bits of exposed granite slope. Through the desolate summits swept ranging, intermittent gusts of the terrible Antarctic wind; whose cadences sometimes held vague suggestions of a wild and half-sentient musical piping, with notes extending over a wide range, and which for some subconscious mnemonic reason seemed to me disquieting and even dimly terrible. Something about the scene reminded me of the strange and disturbing Asian paintings of Nicholas Roerich, and of the still stranger and more disturbing descriptions of the evilly fabled plateau of Leng which occur in the dreaded

Necronomicon

of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred. I was rather sorry, later on, that I had ever looked into that monstrous book at the college library.

On the 7th of November, sight of the westward range having been temporarily lost, we passed Franklin Island; and the next day descried the cones of Mts. Erebus and Terror on Ross Island ahead, with the long line of the Parry Mountains beyond. There now stretched off to the east the low, white line of the great ice barrier, rising perpendicularly to a height of two hundred feet like the rocky cliffs of Quebec, and marking the end of southward navigation. In the afternoon we entered McMurdo Sound and stood off the coast in the lee of smoking Mt. Erebus. The scoriac peak towered up some twelve thousand, seven hundred feet against the eastern sky, like a Japanese print of the sacred Fujiyama, while beyond it rose the white, ghostlike height of Mt. Terror, ten thousand, nine hundred feet in altitude, and now extinct as a volcano.

Puffs of smoke from Erebus came intermittently, and one of the graduate assistants—a brilliant young fellow named Danforth—pointed out what looked like lava on the snowy slope, remarking that this mountain, discovered in 1840, had undoubtedly been the source of Poe’s image when he wrote seven years later:

—the lavas that restlessly roll

Their sulphurous currents down Yaanek

In the ultimate climes of the pole—

That groan as they roll down Mount Yaanek

In the realms of the boreal pole.

Danforth was a great reader of bizarre material, and had talked a good deal of Poe. I was interested myself because of the Antarctic scene of Poe’s only long story—the disturbing and enigmatical

Arthur Gordon Pym.

On the barren shore, and on the lofty ice barrier in the background, myriads of grotesque penguins squawked and flapped their fins, while many fat seals were visible on the water, swimming or sprawling across large cakes of slowly drifting ice.

Using small boats, we effected a difficult landing on Ross Island shortly after midnight on the morning of the 9th, carrying a line of cable from each of the ships and preparing to unload supplies by means of a breeches-buoy arrangement. Our sensations on first treading Antarctic soil were poignant and complex, even though at this particular point the Scott and Shackleton expeditions had preceded us. Our camp on the frozen shore below the volcano’s slope was only a provisional one, headquarters being kept aboard the Arkham. We landed all our drilling apparatus, dogs, sledges, tents, provisions, gasoline tanks, experimental ice-melting outfit, cameras, both ordinary and aerial, aeroplane parts, and other accessories, including three small portable wireless outfits—besides those in the planes—capable of communicating with the

Arkham’s

large outfit from any part of the Antarctic continent that we would be likely to visit. The ship’s outfit, communicating with the outside world, was to convey press reports to the

Arkham Advertiser’

s powerful wireless station on Kingsport Head, Massachusetts. We hoped to complete our work during a single Antarctic summer; but if this proved impossible, we would winter on the

Arkham,

sending the

Miskatonic

north before the freezing of the ice for another summer’s supplies.

I need not repeat what the newspapers have already published about our early work: of our ascent of Mt. Erebus; our successful mineral borings at several points on Ross Island and the singular speed with which Pabodie’s apparatus accomplished them, even through solid rock layers; our provisional test of the small ice-melting equipment; our perilous ascent of the great barrier with sledges and supplies; and our final assembling of five huge aeroplanes at the camp atop the barrier. The health of our land party—twenty men and fifty-five Alaskan sledge dogs—was remarkable, though of course we had so far encountered no really destructive temperatures or windstorms. For the most part, the thermometer varied between zero and 20° or 25° above, and our experience with New England winters had accustomed us to rigors of this sort. The barrier camp was semi-permanent, and destined to be a storage cache for gasoline, provisions, dynamite, and other supplies.

Only four of our planes were needed to carry the actual exploring material, the fifth being left with a pilot and two men from the ships at the storage cache to form a means of reaching us from the

Arkham

in case all our exploring planes were lost. Later, when not using all the other planes for moving apparatus, we would employ one or two in a shuttle transportation service between this cache and another permanent base on the great plateau from six hundred to seven hundred miles southward, beyond Beardmore Glacier. Despite the almost unanimous accounts of appalling winds and tempests that pour down from the plateau, we determined to dispense with intermediate bases, taking our chances in the interest of economy and probable efficiency.