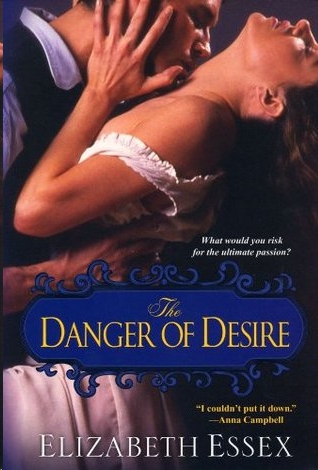

The Danger of Desire

Read The Danger of Desire Online

Authors: Elizabeth Essex

The

D

ANGER

OF

D

ESIRE

ELIZABETH ESSEX

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

EPILOGUE

Teaser chapter

Copyright Page

For my parents, for love, education, and support.

But most especially, for my mother, Carol Craven Robinson, for her lifelong dedication to books and the fine art of reading.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to many people, but most especially: to my delightful editor, Megan Records, for her careful stewardship of all of my books for Kensington Brava; to Kristine Mills-Noble and Franco Accerno for three absolutely magnificent, gorgeous, lush covers; to my agent, Barbara Poelle, for convincing me that writing on a deadline was simple; to Anna Campbell, for her generosity in reading the manuscript and providing a smashing cover quote; and last, but never least, to my brilliant critique partner, Joanne Lockyer, for always finding the right words to encourage me to do my best—three hearty and heartfelt

huzzahs!

CHAPTER 1

London, November 1799

L

ord, but it was cold and raw as a St. Giles curse. Nothing kept out the aching damp. Meggs hugged her arms closer to her sides, tucked her bare fingers up in fists, and quickened her pace along the deserted sidewalk as she and her brother slipped their way through St. James’s dripping streets toward the Strand, looking for a few more likely culls. But drunken lords had been thin on the ground this morning. The icy drizzle had been falling in fits and starts since dawn, and the sky remained an ominous, bone-cold gray.

She hated it. Hated it all—the insidious cold, the incessant rain, the petty larceny—but hunger had a way of sorting out priorities. There was thievery to be done.

“Tell me again.” At her side, Timmy swiped at his cold nose with the back of his sleeve.

For her brother, Meggs pushed the bleak feeling of unease aside.

“We’ll be rich, we will. And we’ll live in a lovely house, a stout cottage, you and me, my lucky Tanner, just the two of us. Someplace warm, like Dorset.”

She had no idea if Dorset really was a warm place. Perhaps she had heard it said once, or perhaps she had been told palm trees grew there. And even she knew palm trees grew only in warm places. But wherever it was they went, she was determined it be warm. They had been cold for far too long.

Almost forever. And today, when London’s creeping, yellow fog was thick with ice, she felt as though it would be winter forever. Days like this, she despaired of ever being dry and warm again. Or full. Her stomach growled in empty resentment.

And so, in the face of such barren grayness, she lied. “We’ll have a house with lots of fireplaces with warm cozy fires, all snug and toasty. And in the summer, a rose garden so the air will always smell nice, not like coal. We’ll have a big garden with an orchard at one end with apples and pears for you to eat whenever you like, and trees for you to climb. And a tree with a rope swing for you to play on.”

Her brother was too young to remember what it had been like before. He’d been barely four years old when they’d been packed off to London. And eight years under old Nan’s deft tutelage couldn’t help but leave its mark.

“When?” he asked with the cynical straightforwardness of a child who was well used to hearing Banbury tales.

“Soon, I think.” Her eyes never stopped combing the pavement, even as her mouth spun fantasy out of the chill air. “There. They’ll do. Look sharp.”

Three rich, sotted culls were ahead, weaving their way homeward from their club. Drunk as lords. Young toffs with more hair and money than wits. Never notice the lowly housemaid they’d barreled into had relieved them of their purses, would they? In their pleasant stupor, buffered from the cares of the world by wealth and copious amounts of good liquor, they would not even see Timmy, the small, whip-quick crossing guard to whom she would pass the take as he chanced by.

Timmy nodded once, then melted across the street, made silent and invisible by the fog. Meggs resisted the urge to give him more instruction, or follow his progress to make sure he was well positioned. It wouldn’t do. Her Tanner was getting old enough to know their business as well as she. If they wanted to eat, they needed to steal.

The men lurched closer, in and then out of the small circles of lamplight, laughing loudly and singing some bawdy tune.

“There was a young girl from Crupp, whose pleasure it was for to tup ...”

Meggs let the lewd lyrics slide past and echo down the street. The one on the left was tallest. Tall Boy’s arms and hands were completely engaged in holding up his drunken comrade, who was draped over his shoulder like a drunk sailor. Tall Boy was happy. His coat flapped open to reveal a bounteous, bulging waistcoat pocket. Tall Boy had been the winner.

And so would she be. Meggs flexed her hands on the handle of her basket and wiped her fingers dry on the inside of her apron, swallowing the jitters that crawled up her throat. It would work. It always worked. Drunks were easy. Easy as taking gin from a dead whore. She gauged the distance and picked up speed, keeping even pace with the rising hammer of her heart, aiming to reach them just as they left the watery circle of lamplight. She’d be in the dark, and they’d never see her until it was too late.

Three yards to go. Two. Eyes and ears stretched open, blind to everything but the waistcoat pocket and deaf from the roaring of her blood, she put her head down and plowed right into them.

And it was dead easy. A turn of her body, a firm shove with the prickly reed basket, and the culls were separated and falling. And there she was, patient as the saints, waiting for the precise moment when his purse eased into her waiting hand, like a ripe plum plucked from a tree.

Then she was racing past and beyond, into the safety of the dark before they had even registered her presence. “Come back, darling,” one of them called. “I’ll make it worth your while.”

He’d already made it worth her while, thank you very much. Meggs dismissed the drunk young culls from her mind as she passed Timmy the take and moved on swiftly into the rising dawn.

But she was wrong. Two blocks later, when they met up, Timmy had already discarded the purse and counted the money. “Flimsies,” he sighed, “and small change.”

Banknotes. Not so good as ready coin. They’d not get full value if they tried to fence them, and they couldn’t very well waltz up Poultry Lane to the Bank of England to exchange them, could they? Get shoulder clapped right there in the lobby, they would. “How much in coin?”

“Two quid, three crowns, six pence.”

She couldn’t look at the disappointment scraped across his pinched face. It was not enough. Why was it never enough?

“We need one more this morning. One good one.” It was always the hardest—that last purse of the morning. After nearly four hours she and Timmy were getting tired, but the toffs were waking up. So much easier to dip them when they were still half-muzzied with drink. “So look sharp, my little Tanner. You clap your peepers on a likely greenhead, and we’ll get a meat pie, after.”

“Each?”

She hated that hopeful tone. The one she always had to disappoint. “To split. But only if we spy a likely toff to tip. So look sharp. Mind the traps.” The last thing they needed was to run afoul of the Constabulary, who were always about in this part of town protecting the deserving rich from the undeserving poor, the criminal element. From thieves like them.

Hugh McAlden’s leg had begun to ache. The cold, wet walk up from Chelsea, all the way to the Admiralty Building in Whitehall, had taken more out of him than he had anticipated. He ought to have taken a walking stick, or gone down river by boat with a waterman, but the morning had promised to be fine. So much for his weather eye.

Normally, the leg only pained him like this when it rained. But this was England. The only place wetter was the bilge of his ship.

His

former

ship. And the only way he was going to regain command of

Dangerous

was by currying the favor of the Admiralty. Thus, gimpy and out of sorts, he presented himself to the porter in the cavernous Admiralty Building in Whitehall and wound his way through the warren of rooms to his appointment.

“Captain McAlden?” the clerk inquired as soon as he found the room. “Admiral Middleton will see you immediately. Please come this way.”

Sir Charles Middleton, recently promoted to Admiral of the Blue, greeted Hugh like an old friend, which they were if giving Hugh dangerous, unsavory assignments and rewarding him heartily with advancement counted as friendship.

“Captain McAlden.” The admiral came though the doorway and held out his hand. “Good to see you, my boy. You’re looking fit. I expected to find you much the worse for wear after hearing of your injuries.”

“I’m improving, sir, I thank you.”

“Good, good.” The admiral refrained from clapping Hugh on the back, but his smile was full of relief. “I was pleased to hear such things of you at Aboukir Bay—how you took

Dangerous

to cut the line to engage the French from behind. Well done, sir, well done, but I expected nothing less from you. The dispatches were full of it. And at Acre. Hell of a thing for a sailor to be wounded in a battle on land, what?” He glanced down. “How’s the leg?”

“Still attached.”

“Ha! We’ll have you back to the fleet in no time. Come walk with me.”

Hugh kept his grimace to himself and limped after Sir Charles, back down the echoing staircase and out the rear of the building toward the parkland beyond. “It’s damnable to be so hobbled and unfit for command,” he said to cover his awkwardness on the stairs. “I don’t know what bothers me more—the leg or being so damn useless.”

“Ah, but that is where you are wrong, Captain. I have every expectation you will be very useful to me—even in your present state.”

“Admiral?”

“I have another interesting assignment for you.”

Hugh found his leg began not to pain him so very much with such a prospect before him. And the weather was improving as well. The damned iced drizzle had at last begun to give way to snow. “More interesting than the last?”

It had been over four years since Sir Charles, who at the time had been an influential member of the Admiralty Board, had sent him off on an

interesting

special assignment. Special meaning unofficial and unacknowledged—at least publicly. But Sir Charles had seen to it Hugh was rewarded with command of

Dangerous

. Which had led to his success at Aboukir Bay and then Acre. And ultimately, his damn wound. But caution had never brought him success or advancement. Completing Admiral Sir Charles Middleton’s unsavory tasks had. “Admiral, I am completely at your disposal.”