The Dark Sacrament (22 page)

Read The Dark Sacrament Online

Authors: David Kiely

Also, in Luke's Gospel, Jesus tells the story of the rich man and Lazarus. The former is suffering in hell and asks that Lazarus, the poor man residing in heaven, be sent back to earth. The rich man fears for his five surviving brothers, and asks that they be warned of the torments that await them if they do not mend their ways. His request is refused on the grounds that the living have the word of Moses and the prophets to persuade them. They should have no need of the testimony of dead men.

And this is the nub of it, according to Canon Lendrum. Those who turn to the occult for answers are demonstrating a lamentable lack of trust in God.

He reminds us of a passage in Deuteronomy: “Let no one be found among you who practices divination or sorcery, interprets omens, engages in witchcraft, or casts spells, or who is a medium or

spiritist or who consults the dead. Anyone who does these things is detestable to the Lord.”

They are also asking for trouble, the canon feels. Doors into the unknown can open. The Gillespies were fortunate that their particular door seems to have opened onto one of the more benign regions of extraphysical existence.

We ask about the nature of the exorcism itself. It is our understanding that it was more a cleansing of the house than a deliverance of Lucy. “Yes, indeed. One can speculate that the lady whom Lucy had seen three times had possibly the greatest emotional attachment to the place. Probably suffered a good deal during the war. The armless soldier could have been the husband; the body part in the shower, the naked boy, possibly sons who died violently. Interesting that Lucy first saw the mistress tidying the videotapes. Asserting ownership, I'd say, then her praying by the wall and the monk praying alsoâ¦trying to come to terms with the tragedy.”

We wonder if any of Lucy's apparitions congregated for the blessing, whether the canon was aware of any “presences.”

He nods. “I did feel a presence, which I suppose could have been that of the mistress. I sensed that if I laid her to rest, the others would follow in due course. I celebrated a Eucharist with the family and prayed that she'd go in the peace of the Lord, where she could meet her loved ones again in the light of God's love. Then I blessed each room in the house and the outbuildings as well.”

“So all in all, everyone was happy,” he concludes. “It is wonderful to participate in such a healing victory. Experiencing the power of God's love in these situations is something neither I nor those afflicted ever forget.”

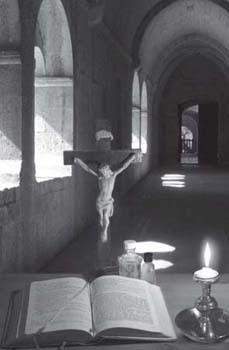

Image 3

The effects of Father Ignatius McCarthy, used during an exorcism. Father Ignatius requested anonymity, and so is not pictured.

THE MONK: FATHER IGNATIUS McCARTHY

A native of County Clare, he is eighty years old and has been a cloistered monk for fifty-three of those years. Despite having left the county of his birth some five decades ago, he has never lost the accent. He speaks softly, and one has to listen closely to catch his words. Yet his gentle demeanor masks an iron will and a fierce intelligence. There is also an air of another time about him; one suspects that the saints and Christian martyrs of antiquity looked and sounded a lot like Father Ignatius.

His call to the religious life came when he was still a child.

“I was enthralled by the whole solemnity and pomp of the Mass,” he recollects. “While other boys were most likely bored by that Sunday ritual, I was enchanted. I remember asking my mother what a priest did besides offering Mass, and she said: âHe dresses in black clothes and prays a lot.' I think maybe she didn't want me getting ideas in that direction.”

But the young Ignatius's dream of becoming a priest did not diminish as he grew older. “I suppose when I got into my teens I became aware of what I'd be giving up, what the monastic life would involve, and that worried me. I'd be burning my bridges, and there would be no turning back. But, fortunately, God's call was louder and stronger than all those petty considerations.”

At age seventeen, he entered Maynooth Seminary in County Kildare to begin his seven years' training.

Following his ordination, he joined the Redemptorist Fathers and served as a missionary in Africa. Ill health forced him to return to Ireland before his five-year tenure was completed. He joined the Cistercian order in 1948 and has been with that community ever since.

“I always had the idea that monks were a lazy crowd who sat about all day thinking deeply about things,” he says with a smile, as he gives us a tour of the grounds. “I got a rude awakening when I came here. Much of the work consisted of heavy farm labor. There are over a hundred acres of arable land surrounding the monastery, and most of it was under crop every year back then. Apart from that, we had a dairy farm with a milking herd of seventy or more cattle.”

The tough labor that characterized his early life has now been replaced by a gentler routine, yet when it comes to spiritual matters, the rigid disciplines remain firmly in place and are embraced with as much fervor as ever. Prayer and meditation are the order of the day.

His day begins at 3:45 a.m., when the Great Silenceâimposed at 9:15 p.m. the previous eveningâis broken by the tolling of the chapel bell.

Vigils, the first office of communal prayer service, start the day. They are followed by Lauds, the second office or morning prayers, at 7 a.m., after which Father Ignatius prepares to say morning Mass. At 8:15 a.m., midmorning prayers, or Terce, are said. This is the shortest office of the day. At noon, midday prayers, Sext, are followed at 2:30 p.m. by None, midafternoon prayer, and Vespers, or evening prayer, at 5:30 p.m. The day ends with Compline, the final office. In between these seven prayer periods, Father Ignatius eats three light meals, reads, and spends time with those visitors who come seeking his help. He retires at 9:15 p.m., entering the Great Silence once more, and sleeps for four to five hours.

His first encounter with the demonic occurred in the 1960s, in a most unlikely place: within the very walls of the monastery.

Brother Francis was a young man in his twenties when he joined the order. Father Ignatius recalls him with sadness. “He was the proud

est person I'd ever metâ¦terribly self-centered and covetous. There was an air of danger about him, and when he'd get angryâwhich was very oftenâyou really feared for your own safety. I remember him throwing a can of oil at me for no reason at all and then laughing when it hit its target. He loved seeing people upset; he seemed to thrive on it. I've noticed that a marked immaturity lies at the heart of all evil, and that there needs to be a degree of dysfunction already in the individual before evil can take hold. Brother Francis ticked every box.

“On several occasions, I noticed his light on in his room in the middle of the nightâ¦and in one of his rare moments of calm I asked him about it. He told me that in the dark something would visit him and press down on his chest. I offered to pray in the room with him. He asked me what good that would do, and in no time he was back to his usual, angry, self.”

After a year Brother Francis was asked to leave.

“He ended up a homeless deviant,” Father Ignatius continues, “and was charged several times with sexual assault, on both women and men. These days he spends his time wandering the roads, I believe. A lost soul in every sense of the word. I always remember him in my prayers, though. Where there is life there is still hope.”

Father Ignatius's introduction to exorcism occurred quite by accident. A fellow priest, Father James, a friend from school days who had been allocated a new parish in the west of Ireland, visited him one day with an unusual story.

He explained that, since moving into the parochial house, he had been having some very strange experiences. On several occasions he had awoken in the early hours to find a young woman standing by the foot of the bed. She was dressed in clothes from ancient times and was badly disfigured down one side of her face. The priest, sensing that she was a lost soul, began praying for her. Within a matter of days, the visions ceased. However, things took a more sinister turn when one morning he found his breviary not on his study desk where it always sat but lying face down on the floor. From then on, other religious objects in the house came under attack.

“He was terribly troubled when he came to see me,” Father Ignatius recalls, “and asked me if I would come to the house and pray. I did, of course, without hesitation. Father James reported that my intervention proved successful, and after that word spread. I was called upon to assist in other such cases. I take no credit for these successes,” he continues modestly. “We priests are simply channels through which God does his work. Our job is to remain firm in faith and never fear, because the Devil is as nothing in the face of God the Almighty.”

Father Ignatius has always believed in the existence of evil.

“I'm from the old school,” he asserts, “however antiquated that may sound. As a Catholic priest I believe in the Gospels, in Jesus's life as the supreme example of how we should live. Jesus cast out many demons during his ministry and spoke persistently about the Devil and his works. The fact that Jesus spoke so clearly about the reality of Satan is the most powerful evidence we have. So we priests are duty bound to continue his work. We can't cherry-pick those aspects of Jesus's ministry we choose to accept as gospel and ignore the idea of Satan simply because it is distasteful to our so-called modern minds.”

He has seen a rise in the instances of demonic oppression over the past few yearsâbut is not surprised.

“Materialism and consumerism have eroded spiritual values,” he concludes, “but they don't deliver the peace and happiness people crave. We satisfy our egos at the expense of our souls. The result of all this moral decay means that Ireland may now be the second-richest country in Europe, but at what a cost! We have the highest incidence of alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and teenage pregnancy in Europe as well. Pope John Paul II, when he visited Ireland in 1979, warned of this moral decline. He said: âYour country seems in a sense to be living again the temptations of Christ. Ireland is being asked to prefer the “kingdoms of this world with their splendor” to the kingdom of God. Satan, the tempter, the adversary of Christ, will use all his might and deceptions to win Ireland for the way of the worldâ¦. Now is the time of testingâ¦.'”

These days, this humble, devout man leaves the monastery only to deal with those cases that have defeated other priestsâin particular,

when a haunting takes on an antireligious character, indicative of the work of hostile spirits or demons.

He spends most days in solitude and prayer, yet is forever willing to receive those who come to the monastery seeking his prayers and wise counsel.

Truly this man is “in the world” but not “of the world.”

It is said that all it takes for evil to flourish is for good men to do nothing. The charge of inaction in the face of spiritual danger is not one that can be laid at the door of this devout and dedicated monk.

The following five cases complement those of his Anglican counterpart, Canon William Lendrum. Father Ignatius regards each of them as a cautionary tale, but all serving to remind the reader of the formidable power of prayer.

CONNEMARA, COUNTY GALWAY, 1974

A blue Vauxhall Astra sits idling by a farmhouse gate on a hot Sunday morning in mid-June. At the wheel is a young man, one elbow resting on the door frame, whistling to himself as he gazes beyond the windshield. Occasionally, he flicks a glance at the whitewashed cottage but, as yet, there is no sign of life. He sounds the horn a second time: one short, sharp blast that shatters the quiet of the countryside. But still nothing stirs. He lights another cigarette and sighs.

Dan McBride has been ferrying the Dwyer brothers to and from Mass every Sunday for the past eighteen months. He is not particularly fond of the pair, but his mother feels sorry for them. Both are bachelors in their late seventies, taciturn men who rarely venture beyond the confines of the twenty-acre farm that sustains them.

Dan grows impatient. He tosses the half-smoked cigarette into the hedge and is about to step out of the car, but at that moment, he hears the front door of the cottage opening. He watches Edward and Cornelius Dwyer emerge into the sunlight and shuffle up the path. Edward, as usual, is carrying a plastic gallon container.

The men climb into the car and mumble a greeting. Their routine never varies. They wear the same clothes, nod politely, and use the same words of greeting before falling silent. Cornelius settles himself

in the backseat and lays the two missals on his lap. Edward rides in front with the container between his knees. They are ready to leave.

The tires of Dan's car crunch over the rough graveled lane, which winds for a good mile to the main road. He remarks on the weather and is answered by a grunt from Cornelius.

On arriving at the church, Edward makes the same puzzling request of Dan that he has been making every Sunday: “You wouldn't get that filled with holy water while you're waiting?”

“Right-o,” says Dan.

While the brothers attend the forty-five-minute service, Dan fills the container from a barrel of holy water by the sacristy door. His chore done, he passes the time by reading the newspaper and smoking a couple more cigarettes.

On this particular Sunday, however, Dan's curiosity gets the better of him. Back at the Dwyer cottage, he decides to ask the question that has been gnawing at him for the longest time.

“Tell me something,” he says, as the men are getting out of the car. “Why d'you need so much holy water every Sunday? D'you make the tea with it, do yous?”

The brothers turn as one and eye him sourly. “You needn't give us a lift again,” Cornelius says.

“No, you needn't give us a lift again,” Edward repeats. “We'll get somebody else to take us to Mass from now on.”

Dan can only stare after the pair as they shuffle back down the path, Edward carrying the container of holy water in his right hand, Cornelius gripping the missals in his left.

“That's gratitude!” Dan shouts after them. Angry, he guns the engine and turns in the yard. His final glimpse of the brothers is in the rearview mirror as they enter the farmhouse without a backward glance. He will never see them again.

Six months later, both Dwyers are dead, having passed away within weeks of each other.

Â

There were nine siblings in the family, four of whom died in infancy. Cornelius and Edward were the eldest. Two sisters had married and were living in England. Shane, the sole surviving brother, was also married with a young family and lived close to the paternal home.

It seems that there was bad blood in the Dwyer line. Shane discovered, on his brothers' demise, that the unthinkable had happened: they had bequeathed the family farm to neighbors. He had taken for granted that he would inherit. He was shocked. Land that had been in the Dwyer name for generations now belonged to outsiders.

He vowed to buy it back, if only to restore the good name of the Dwyers and their standing within the community. But, as the years passed, the demands of his own family took priority.

Shane always felt keenly the loss of the land. Partly to heal the hurt, he threw himself into the education of his eldest son, Shane Jr., believing that the boy, by excelling in college, would win back the self-respect taken away from the father. But, even after decades had passed, the dispossessed man still hankered after the “home place,” as he called it. His dying wish was that Shane Jr. might close the gap that his brothers had so cruelly breached.

In January 2002, that wish was fulfilled. His son bought back the land. He built a new home on the footprint of the old cottage in memory of his dear father and, in so doing, restored the family name to that little patch of Connemara that had always belonged to the Dwyers.

The modern, two-story dwelling occupies an enviable position within the shadows of the Twelve Pins mountain range. It is a peaceful place, far from the main road and embraced to some extent by the rough natural beauty of Ireland's western seaboard. There are no other homesteads in sight.

We are sitting in Shane Dwyer's kitchen as he relates his story. He is thirty-four, a tall, lean, dark-haired man with alert brown eyes and an easy manner. He and his wife, Moya, are both high-school teachers. They have two children: Emma, age nine, and Rory, five.

“Yes, it is very quiet here,” Shane agrees, when we comment on how fortunate he is to be living amid such tranquillity. “But don't let that fool you. The past two years have been anything but peaceful.”

He is confirming what has already been told to us. We are here in this isolated part of County Galway because the events that took place in the Dwyer home caused alarm among quite a few clergymen.

It began on June 10, 2004, the day the family took possession of their lovely new home. It was so much more spacious than their old one, a row house in Clifden. One would have thought, then, that everyone would be pleased, but that was not the case.

“I well remember the day we moved in,” Shane tells us. “I felt that Moya wasn't happy, but I put it down to the change of scene.”

While the children played outside in the yard, the parents spent that first sunny afternoon unwrapping bric-a-brac and hanging pictures. They concentrated on the two small rooms to the front of the house, the “green room,” or lounge, to the left of the front door and the “red room,” or parlor, to the right.

Unlike the rest of the house, these rooms are small. They faithfully follow the floor plan of the old cottage. In fact, the rooms, together with the hall and pantry, occupy the exact area on which the original Dwyer home stood. The couple had received a heritage grant to preserve this historical feature.

“Granny's Bible, where do you think?” asked Shane, hefting the heavy, leather-bound book in both hands.

“Oh, the parlor. Don't want the kids to get their hands on it.” Moya took it. “Here, I'll do it.”

She carried it down to the red room. Despite the heat of the day, there was a cold feel to it. She remembers that there was something about the room that made her uneasy. It may have been the thickness of the walls; the old cottage walls were designed to provide shelter throughout the long, damp Connemara winter. Moya stood up on a chair and placed the Bible on a high shelf to the left of the fireplace. As she did so, she heard the door shut softly behind her.

“Shane, is that you?”

No answer.

Again, a slight shiver ran through her. She had the sensation of someone, or something, having entered the room. She rushed to the door and pulled it open. But there was no sign of Shane. Instead, she found him in the kitchen.

“Why did you do that?” she asked.

“Do what?”

“You shut the door on me. In the red room.”

“I didn't.”

“Yes, you bloody well did! And it's not funny.”

“Look, the wind must have done it.”

“The wind. Look at those trees, Shane!” She went to the window. “They're as still as statues. There's not a breath of wind today, and besides, the windows at the front

are not open

.”

“Well, maybe it just swung to. New doors sometimes do that.”

“Yeah, right. If it happens again I'll want a better explanation.” She busied herself unwrapping another item.

Shane said nothing. He knew his wife was not too happy with the move to the country. Born and raised in the lively, bustling town of Clifden, she had relinquished a whole way of life to live in “the back of beyond,” as she called it. Shane was fulfilling his dead father's wish, and he felt guilty that Moya was part of that wish tooâwhether she liked it or it. He had noticed that every time they visited the house during its construction, Moya's mood changed. On the return journey she would say hardly anything at all, and it would take a while for her to become “herself” again.

He hoped that things would settle down once they had moved in. But here they were, barely two hours in the place, and she was accusing him of mischief. The signs were not good.

“I'll make some coffee,” he said, trying to lighten the atmosphere.

Moya was not listening. She was looking thoughtfully at the picture of the Sacred Heart. Shane had just hung it near the stove, as his parents had done in their old home.

“I don't want it there,” she said abruptly. “I want it over the mantelpiece in the red room.” She reached into a box on the floor and hauled out a crucifix. “And this in the green room, on the back wall. Can you do that?

Now,

please?”

He nodded. He was unsure of what to say. “Moya knew better than I did that something was wrong with the house. She told me later that she got an inkling on that first day, the day we moved in. She didn't use the word

evil

but I knew what she meant. She felt that the holy picture and crucifix should be there. She didn't know exactly why she felt that, but I trusted her intuition.”

The months passed. The house became a home. Shane was gratified to be able to fulfill his father's dream of having the land restored to the Dwyer family. As time wore on, he grew to love the house, to feel that he belonged within its walls. Moya had overcome her initial disquiet. Emma settled into the local school and made friends. They were living the idyll.

But, before too long, there were signsânothing overt, but small signsâthat things were not quite right. The trouble began with three-year-old Rory.

Emma and Rory each had a bedroom on the first floor. It was Shane's habit, having tucked in the little boy, to check for the boogeyman. It was something he had always done; he supposed he would be doing it for quite some time to come.

That particular evening, a little after seven o'clock, he made a great show, as usual, of crouching and peering under the child's bed.

“Nope, no boogeyman,” he assured Rory, getting to his feet again.

“But the boogeyman's not down there, Daddy!” The boy was looking fixedly toward the other side of the room. “He's standing at the window.”

“Right, I'll open the window and throw him out.”

He made a great show of striding purposefully across the room.

“It's all right now, Daddy. He just went into the wall.”

Shane smiled, remembering his own childhood and the host of imaginary friends he hadâthe fairies, the hobgoblins, and creatures

slight and small. Yes, children have rich imaginations, he mused. A pity they lose it all so quickly, when boring adulthood kicks in.

He gave it no further thought. He continued to check under the bed each night for the boogeymanâand Rory continued to insist that “the bad man” was actually by the window. Then the child announced one night that he could dispense with his father's sentinel services.

“There's no need, Daddy. Michael comes in and sends him away.”

Shane smiled, ruffled Rory's blond curls. “Who's Michael, then?”

“He sits on the roof and he's got wingsâ¦andâ¦and when you go out, he comes in and he sends the bad man away.”

Again, images of elves and fairies came to mind. Shane filed “Michael” away as yet another denizen of a little boy's fantasy world. At the same time, minor incidents were occurring in the Dwyer home. Each by itself was trivial, but taken together they were forming a pattern.

“Items would go missing or get misplaced,” Shane explains. “You might set your coffee cup on the table, then go to get something in another room, come back, and discover that your cup had been moved to the draining board. Or we'd find the telephone off the hook for no good reason. At first we blamed each other, then we blamed the children.”

The trifling anomalies were to give way to something more ominous. It occurred during the approach to Christmas.

“It was bizarre,” Shane says. “Moya had put the Bible in the red room. Three mornings in a row we found it lying smack bang in the middle of the floor, and always opened at the same pages: Isaiah twenty-eight to twenty-nine.”

He sees our look of bemusement. He fetches the Bible and turns to the chapters in question. “It seems to be all about the fall of Jerusalem and the demon drink,” he says. “And before you get any ideas, I never touch the stuff. Never have.”

He reads a verse or two.

Woe to the crown of pride, to the drunkards of Ephraim, whose glorious beauty is a fading flower, which are on the head of the fat valleys of them that are overcome with wine!

Behold, the Lord hath a mighty and strong one, which as a tempest of hail and a destroying storm, as a flood of mighty waters overflowing, shall cast down to the earth with the hand.

The crown of pride, the drunkards of Ephraim, will be trampled under feetâ¦.

“We couldn't understand what any of it meant,” Shane confesses, “but it was leading up to something, and we soon found out. That Christmas, all hell broke loose.”

The phrase is an apposite one. The first holiday season in their new home would herald a catalog of events so terrifying, so extraordinary, and of such frequency, that one is left wondering how anyone could endure it and remain mentally and emotionally unscathed.