The Dawn of Innovation (43 page)

Read The Dawn of Innovation Online

Authors: Charles R. Morris

Alexander Lyman Holley, scion of the Salisbury Holleys and son of Alexander Hamilton Holley, the forge owner, edge-tool maker, and Connecticut governor, almost single-handedly dragged America into the steel age. As a young man, Lyman negotiated iron contracts with Springfield's Roswell Lee, frequently visited the Collinsville Axe works, and counted Sam Collins's son among his close friends. Graduating from Brown with an engineering degree, he went to work for George Corliss and then, though still young, shaped a career as an engineering consultant and a science journalist, focused on machinery and metallurgy. A brilliant draftsman and a fluent writer, he was a regular in the pages of the

New York Times

and the editor of several technical journals. On a European trip studying ordnance, he encountered the Bessemer process that had revolutionized British steel production, and arranged with Bessemer to act as his American agent. That required mediating substantial patent challenges, which were resolved by the formation of a patent-pooling trust to oversee compliance and collect royalties.

bs

New York Times

and the editor of several technical journals. On a European trip studying ordnance, he encountered the Bessemer process that had revolutionized British steel production, and arranged with Bessemer to act as his American agent. That required mediating substantial patent challenges, which were resolved by the formation of a patent-pooling trust to oversee compliance and collect royalties.

bs

Â

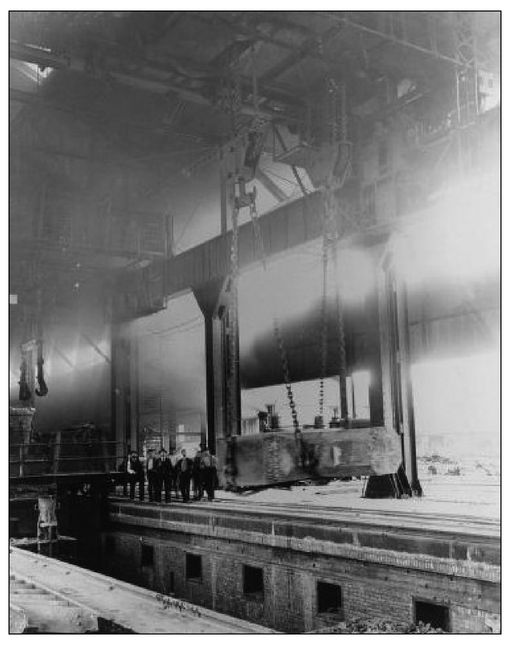

90-ton Ingot.

By the end of the nineteenth century, American steelmakers, led by Carnegie Steel, had far surpassed the British in total steel production, and with the exception of some specialty products could match the British in steel quality. The picture shows a 90-ton steel ingot poured at the Carnegie Homestead plant in 1892.

By the end of the nineteenth century, American steelmakers, led by Carnegie Steel, had far surpassed the British in total steel production, and with the exception of some specialty products could match the British in steel quality. The picture shows a 90-ton steel ingot poured at the Carnegie Homestead plant in 1892.

Holley then designed most American steel plants. Of the eleven Bessemer plants in America, six were entirely his design, on three others he was a design consultant, and the remaining two were copies of his other plants. His signature piece was Andrew Carnegie's Edgar Thomson plant, the ET, near Pittsburgh. Opening in 1875, it was the first Holley was able to build from scratch, and he made it a model of continuous-flow processing. Pig iron was melted in twelve-ton cupolas and poured directly into a giant Bessemer converter. After the conversion had been completed,

the converter was tipped and poured the steel into a moving train of ingot molds on an internal rail. The rail system transported the ingots to cutting and trimming machinery and then to mechanical rail rollers, where they were “pressed with uniformity and precision . . . by hydraulic fingers [and therefore] . . . cool almost perfectly straight,” which Holley contrasted to hand straightening “which cannot, of course, be precise and uniform.”

5

the converter was tipped and poured the steel into a moving train of ingot molds on an internal rail. The rail system transported the ingots to cutting and trimming machinery and then to mechanical rail rollers, where they were “pressed with uniformity and precision . . . by hydraulic fingers [and therefore] . . . cool almost perfectly straight,” which Holley contrasted to hand straightening “which cannot, of course, be precise and uniform.”

5

Subordinating the plant design to the requirements of the internal work flow was a Holley mantra. At the ET, the plant was “a body shaped by its bones and muscles, rather than a box into which bones and muscles had to be packed.”

6

Work-in-process always moved from one station to the next by rail, loading and unloading was always mechanical, and the direction of loading was always down. Other innovations, like snap-out converter bottoms for brick relining, were all designed to maximize production uptime.

6

Work-in-process always moved from one station to the next by rail, loading and unloading was always mechanical, and the direction of loading was always down. Other innovations, like snap-out converter bottoms for brick relining, were all designed to maximize production uptime.

Integration was pushed much further just a few years later, when the blast furnaces that smelted iron ore were moved to the steel plant. The new iron was then charged directly from the furnaces into the Bessemer converters, eliminating the necessity of transporting and remelting the pigâa step akin to Paul Moody's integration of textile spinning and weaving. Finally, the ET plant site was at the intersection of two rivers and two major rail lines, all with direct connections to the plant's internal rail system to simplify loading and unloading.

Carnegie was America's greatest steel tycoon. He had started as a telegraph boy at the Pennsylvania Railroad, working directly for Tom Scott, the boss of operations. He rose quickly as the fair-haired boy of both Scott and Edgar Thomson, the road's president; along with Scott and Thompson, he grew rich by looting the company. The three formed a series of businesses headed by Carnegie, with Scott and Thomson as silent partners, selling sleeping cars, iron, bridges, and other gear to the Pennsylvania on preferential terms. Scott was nearly fired when the board discovered their game. Cut adrift, Carnegie cast about for a new career; on a trip to England, he visited its vast new Bessemer plants and saw his future.

Carnegie remained remote from the factory floor, although he loved to dabble in the details. His plants were run by a succession of great managers and steel techniciansâ“Captain” Bill Jones; Henry Frick, who had created the coke industry before joining Carnegie; and Charlie Schwab. But Carnegie was the ideal client for Holley. His management target was always market share, not profits, so he kept a laser focus on through-put, mechanization, and reduced manningâso-called hard-driving. Bill Jones, who patented a number of steelmaking processes, created a stir just six years after the ET opened by telling a meeting of British engineers that his plants got twice the output from a comparable converter as the British did. Holley, whom the British viewed as an honest broker, confirmed the claim. The secret wasn't faster processingâthe laws of physics determined thatâbut much less downtime.

As Carnegie's market share grew, he acted as the industry price disciplinarian. If markets turned down, he was the first to cut price and increase share. By the mid-1880s, the industry's rail-pricing standard hovered around the long-outdated tariff level of $28 a ton. (British export prices, pretariff, were about $33 a ton for rail-quality steel.) During a collapse in the rail market in 1897, Carnegie drove prices all the way down to $14 a ton to keep his plants running full, and

still

made record profits. Elbert Gary, later the president of US Steel, observed that Carnegie had been on the brink of “driv[ing] entirely out of business every steel company in the United States.” By the time of the 1901 US Steel consolidation, Carnegie controlled about a quarter of American steel production, which was equivalent to about half the total British output.

7

STANDARD OILstill

made record profits. Elbert Gary, later the president of US Steel, observed that Carnegie had been on the brink of “driv[ing] entirely out of business every steel company in the United States.” By the time of the 1901 US Steel consolidation, Carnegie controlled about a quarter of American steel production, which was equivalent to about half the total British output.

7

Far more than any other big American industry, the rise and dominance of American petroleum in the nineteenth century is the story of one company, Standard Oil, and one man, John D. Rockefeller. Rockefeller, from middle-class farming stock, started his career in dry goods and, in 1861, invested with his dry-goods partner in a new oil refinery in the booming new

“rock oil” district of western Pennsylvania. Upon a firsthand inspection, he found the business so attractive that he took over as day-to-day manager. Four years later, he bought out his partners, opened his second refinery, and built oil-shipping facilities in New York. (About 70 percent of oil was exported from the earliest days.) From the start, Rockefeller seems to have envisioned the industry as a single, integrated, continuous-flow process operation from the wellhead to final user, and he moved directly and inexorably to make that a reality. By 1870, when he reorganized as the Standard Oil Company, he was already the biggest refiner in the world.

“rock oil” district of western Pennsylvania. Upon a firsthand inspection, he found the business so attractive that he took over as day-to-day manager. Four years later, he bought out his partners, opened his second refinery, and built oil-shipping facilities in New York. (About 70 percent of oil was exported from the earliest days.) From the start, Rockefeller seems to have envisioned the industry as a single, integrated, continuous-flow process operation from the wellhead to final user, and he moved directly and inexorably to make that a reality. By 1870, when he reorganized as the Standard Oil Company, he was already the biggest refiner in the world.

Rockefeller won his markets by concentrating fanatically on reducing costs and increasing efficiency. Refining was already developing a strong technical base, with good temperature controls, use of super-heated steam, much larger-scale equipment, and increased focus on capturing waste for useful by-products, like cold creams. After joining with the Pennsylvania's president, Tom Scott, in a misconceived attempt to create an oil shipping cartel, Rockefeller quietly bought up nearly all of the other Cleveland refiners. He was never a haggler and was happy to pay premiums for transactional speed. Just showing a target Standard's books was usually enough to close a deal, for no competitor ever came close to matching Rockefeller's profit margins. Targets always had the choice of being paid stock or cash, and Rockefeller always recommended taking stock. Most opted for the cash; the ones who took stock and held on to it became very rich.

Once he owned all the Cleveland refiners, Rockefeller scrapped them all and built an entirely new refinery complex comprising six state-of-the-art production sites, each concentrated on a single distillate for processing efficiency. (Kerosene for lighting dominated sales in the nineteenth century, but there were also lucrative markets in lubricants, naphtha, benzene, and other distillates.) The new plant equated to about a quarter of the country's refinery capacity and was almost certainly the most efficient. At roughly the same time, Rockefeller began to take over the major railroads' oil collection, loading, and dock facilities. He also generally stood ready to finance upgraded tank cars or help fund important line extensions, and he was willing to guarantee shipping volumes in return for lower shipping prices.

With the Cleveland consolidation behind him, Rockefeller quietly proceeded to take over almost all the rest of the nation's refineries. It happened very fast. Rockefeller simply visited each of the top regional refineries, in New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore, and nearly all of them agreed to merge with Standard. These were all powerful businessmen, with giant egos, who had built nearly the same scale of operations Rockefeller had. But without any obvious strife they joined Standard under Rockefeller's leadership, dramatic testimony to the power of the Rockefeller personality at first hand.

All of the acquisitions were executed in secrecyâthere were no laws about such things in the 1870s. They all kept their names and current executives, but they all took strategic direction from Rockefeller. With Standard's coffers behind them, they all stepped up the pace of acquisitions within their own operating regions, again with few signs of the changes afoot. The immense consolidation became known only in 1879, when Henry Rogers, a Standard distillation expert, was asked during congressional testimony to estimate the share of national refining capacity owned by Standard Oil. He thought for a minute and guessed that it was “from 90 to 95% of the refiners of the country”âas jaws dropped throughout the hearing room.

8

8

Standard's global near monopoly was not challenged until the mid-1880s, when the Nobel brothers' Russian Baku fields began exporting into Europe. But it was still in a class by itself. From 1887 through 1896, Carnegie's collection of steel, iron, iron ore, coke, and related businesses earned a cumulative $41 million; over the same period, Standard Oil earned $189 million, about four and a half times as much.

Rockefeller and Standard played very rough when they were building their franchise. Doing business in nineteenth-century America was much like selling airplanes in today's Middle East. Bribing local officials was standard practice, and there is at least one documented instance in which Rockefeller clearly committed perjury on a witness stand. But the broader story that Rockefeller's Standard Oil won its position by “secret railroad rebates” and other illegal monopolistic practices has little basis. The United States had no laws against railroad rebates or monopolies when Rockefeller was building his business, and claims by the contemporary muckraker Ida Tarbell and many subsequent Rockefeller biographers that they were “against the common law” are not supported even in the Supreme Court's 1911 decision breaking up the company.

Â

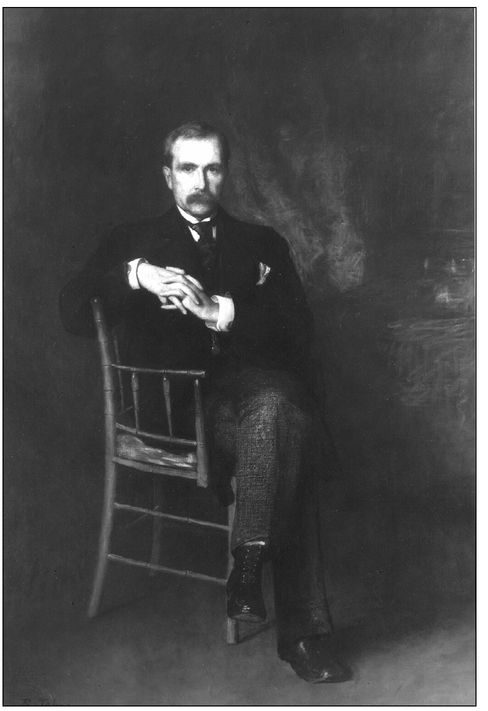

John D. Rockefeller.

This portrait of Rockefeller was painted when he was in his fifties and at the height of his powers. It captures some of the powerful aura that for several decades allowed him to utterly dominate a major industry without, it seems, ever raising his voice.

This portrait of Rockefeller was painted when he was in his fifties and at the height of his powers. It captures some of the powerful aura that for several decades allowed him to utterly dominate a major industry without, it seems, ever raising his voice.

Once Rockefeller eased out of day-to-day management by about 1895, “administrative fatigue” seems to have set in at Standard.

9

John Archbold, Rockefeller's successor, visibly began to monetize Standard's position. Equity returns jumped about two-thirds, from the rather modest average 14.3 percent in Rockefeller's day to 24.4 percent under Archbold. As the company lost its entrepreneurial aggressiveness, its refinery market share dropped to only about 65 percent. Standard was also late to recognize either the opportunities in gasoline or the threat that electricity posed to its kerosene franchise. The 1911 Supreme Court decision mandating the breakup did Rockefeller a favor. Freed from the lassitude at the Trust headquarters, the thirty-four erstwhile subsidiaries almost all greatly improved their performance. Adjusted for inflation, their rocketing stock prices made Rockefeller possibly the richest man in history.

9

John Archbold, Rockefeller's successor, visibly began to monetize Standard's position. Equity returns jumped about two-thirds, from the rather modest average 14.3 percent in Rockefeller's day to 24.4 percent under Archbold. As the company lost its entrepreneurial aggressiveness, its refinery market share dropped to only about 65 percent. Standard was also late to recognize either the opportunities in gasoline or the threat that electricity posed to its kerosene franchise. The 1911 Supreme Court decision mandating the breakup did Rockefeller a favor. Freed from the lassitude at the Trust headquarters, the thirty-four erstwhile subsidiaries almost all greatly improved their performance. Adjusted for inflation, their rocketing stock prices made Rockefeller possibly the richest man in history.

Other books

Hunger by Michael Grant

Little Face by Sophie Hannah

House of Bells by Chaz Brenchley

The Daisy Club by Charlotte Bingham

Any Resemblance to Actual Persons by Kevin Allardice

His Good Girl by Dinah McLeod

The Bloody Ground - Starbuck 04 by Bernard Cornwell

Crash & Burn by Jaci J

A Deadly Brew by Susanna GREGORY

Someone Like You by Cathy Kelly