The Day of Battle (22 page)

Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #General, #Europe, #Military, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Campaigns, #Italy

They fell, writhing and jerking in the dust, then lurched to their knees, begging, only to be shot down again. Cries filled the morning—“No! No!”—amid the roar of the gun and the acrid smell of cordite. Three prisoners broke for the trees; two of them escaped. West stopped to reload, then walked among the men in their pooling blood and fired a single round into the hearts of those still moving. When he was done, he handed the weapon back to Brown. “This is orders,” he said, then rousted the nine chosen for interrogation to their feet, wide-eyed and trembling, and marched them off to find the division G-2. Thirty-seven dead men lay beside the road, and their shadows shrank beneath the climbing sun as though something were being drawn up and out of them.

Five hours later, it happened again. As Sergeant West herded his surviving charges to the rear, German tanks and half-tracks counterattacked, recaptured the Biscari airfield, and drove the 180th across a ravine south of the runway. The brawling would continue throughout Wednesday afternoon until the enemy was again routed, this time for good. During the fight, Company C of the 1st Battalion swept down a deep gulch, taking a dozen casualties from machine-gun fire before white flags waved from an expansive bunker carved into the slope. At one

P.M

., three dozen Italians emerged, hands up, five of them wearing civilian clothes. Ammunition boxes, filthy bedding, and suitcases lay strewn about the bunker.

In command of Company C was Captain John Travers Compton. Now twenty-five, he had joined the Oklahoma Guard in 1934. Compton was married, had one child, earned $230 a month—minus a $6.60 deduction for government insurance—and had been consistently rated “excellent” or “superior” on performance evaluations. Standing on the hillside, bleary with fatigue, he ordered a lieutenant to assemble a firing squad and “have these snipers shot.” The squad soon formed—several men volunteered—and Compton barked the commands even as the Italians pleaded for his mercy: “Ready. Aim.

Fire.

” Tommy-gun and Browning Automatic Rifle fire swept down the gulch, and another thirty-six men fell dead.

The next day, at 10:30

A.M

., Lieutenant Colonel William E. King drove his jeep up the Biscari road toward the now secure airfield. It was said that

King had been temporarily blinded during World War I, and that the ordeal had propelled him into the ministry as a Baptist preacher. He now served God and country as the 45th Division chaplain, admired for his generosity and the brevity of his sermons. A dark mound near an olive grove caught his eye, and he stopped the jeep, mouth agape, to investigate.

“Most were lying face down, a few face up,” King later recalled. “Everybody face up had one bullet hole just to the left of the spine in the region of the heart.” A majority also had head wounds; singed hair and powder burns implied the fatal shots had come at close range. A few soldiers loitering nearby joined the chaplain, protesting that “they had come into the war to fight against that sort of thing,” King said. “They felt ashamed of their countrymen.” The chaplain hurried back to the division command post to report the fell vision.

Omar Bradley had already got wind of the massacre, and he drove to Gela to tell Patton that fifty to seventy prisoners had been murdered “in cold blood and also in ranks.” Patton recorded his reaction in his diary:

I told Bradley that it was probably an exaggeration, but in any case to tell the officer to certify that the dead men were snipers or had attempted to escape or something, as it would make a stink in the press and also would make the civilians mad. Anyhow, they are dead, so nothing can be done about it.

Two war correspondents who had seen the bodies also appeared at Patton’s headquarters to protest these and other prisoner killings. Patton pledged to halt the atrocities, and the reporters apparently never printed a word. To George Marshall on July 18, Patton wrote that enemy troops had booby-trapped their dead and “have also resorted to sniping behind the lines”; such “nefarious actions” had caused “the death of quite a few additional Italians, but in my opinion these killings have been thoroughly justified.”

Bradley disagreed and, Patton told his diary, “feels that we should try the two men responsible for the shooting of the prisoners.” An investigation by the 45th Division inspector general found “no provocation on the part of the prisoners…. They had been slaughtered.” Patton relented: “Try the bastards.”

Captain Compton contracted malaria soon after the Biscari killings, and not until he had recuperated in late October would he be secretly court-martialed. The defense argued that Patton’s pep talk in Oran had been tantamount to “an order to annihilate these snipers.” “I ordered them shot because I thought it came directly under the general’s instructions,”

Compton testified. “I took him at his word.” The military prosecutor asked not a single question on cross-examination. Compton was acquited and returned to the 45th Division.

Killers are immortal,

Patton had declared, but that too was wrong: Compton would be killed in action in Italy on November 8, 1943. A fellow officer in the 45th provided his epitaph: “Good riddance.”

Sergeant West’s case proved more convoluted. Like Compton, he was examined by psychiatrists and declared sane. He, too, claimed that Patton’s rhetoric had incited him to mayhem, while conceding that he “may have used bad judgment.” His conduct, he told the court-martial, “is something beyond my conception of human decency. Or something.” The tribunal concurred and ruled that he had “with malice aforethought, willfully, deliberately, feloniously, unlawfully and with premeditation, killed 37 prisoners of war, none of whose names are known, each of them a human being.”

West was sentenced to life in a New York penitentary. Yet he never left the Mediterranean during the war, nor was he dishonorably discharged, and he continued to draw his $101 a month, plus various family allowances. Colonel Cookson, the 180th regimental commander, later said, “The whole tendency in the thing was to keep it as quiet as possible.” A few weeks after West’s conviction, Eisenhower reviewed the case. If West were sent to a federal prison in the United States, the Biscari story likely would become public; if he were kept confined in North Africa, perhaps the enemy would remain ignorant of the massacre. Eisenhower “feared reprisal to Allied prisoners and decided to give the man a chance,” Harry Butcher wrote in his diary. “[West] will be kept in military confinement…for a period sufficient to determine whether he may be returned to duty.”

That period amounted to a bit more than a year. West’s family and a sympathetic congressman began pestering the War Department for news of “the most thorough non-com” in the U.S. Army. On November 23, 1944, he was granted clemency on grounds of temporary insanity and restored to active duty, though shorn of his sergeant’s stripes. Classified top secret, the records of the courts-martial would remain locked in the secretary of the Army’s safe for years after the war lest they “arouse a segment of our citizens who are so distant from combat that they do not understand the savagery that is war.”

Those who knew of the killings tried to parse them in their own fashion. Brigadier General Raymond S. McLain, the 45th Division artillery commander, concluded that in Sicily “evil spirits seemed to come out and challenge us.” Patton wrote Beatrice, “Some fair-haired boys are trying to say that I killed too many prisoners. The more I killed, the fewer men I lost, but they don’t think of that.” And a staff officer in the 45th wrote, “It was not

easy to determine what forces turned normal men into thoughtless killers. But a world war is something different from our druthers.”

Nobody really knows what he’s doing,

Bill Mauldin had written of his first week in combat with the 180th Infantry. Yet other primal lessons also could be gleaned, from Licata to Augusta. For war was not just a military campaign but also a parable. There were lessons of camaraderie and duty and inscrutable fate. There were lessons of honor and courage, of compassion and sacrifice. And then there was the saddest lesson, to be learned again and again in the coming weeks as they fought across Sicily, and in the coming months as they fought their way back toward a world at peace: that war is corrupting, that it corrodes the soul and tarnishes the spirit, that even the excellent and the superior can be defiled, and that no heart would remain unstained.

N

I

SLAND

R

EDOUBT

“Into Battle with Stout Hearts”

T

HE

command car purred through the thronging soldiers, the big open car with three compasses salvaged from crashed Messerschmitts. Heedless of the raised dust, the troops pressed close, not just to snatch at the cigarette packs tossed from the backseat by their commanding general, but for a glimpse of the great man himself. At 147 pounds and just five foot seven even in his chukka boots, General Bernard Law Montgomery offered little to see: a black beret hid his thinning hair, and the khaki shirt—sleeves rolled to the elbows, tail tucked into his baggy shorts—was unadorned but for the Eighth Army flashes stitched to both shoulders. The Sicilian sun accented every cusp and serif in his narrow face, and made the luminous blue eyes even icier. Perhaps aware that he resembled “a rather unsuccessful drygoods shopkeeper,” as a Canadian correspondent wrote, the general preferred sitting alone in back so “there won’t be any doubt which one is me.” As he flicked his Egyptian fly whisk, one observer thought him “tense as a mousetrap,” but when the car stopped and he stood on the seat his raspy voice carried with the authority of a man accustomed to being heard. “I advise all of you to leave the Eyetie wine alone. Deadly stuff. Can make you blind, you know.” He flicked the swish. “I will make good plans. I wouldn’t be here today if I didn’t make good plans,” he said. “The campaign is going well. The German in Sicily is doomed. Absolutely doomed. He won’t get away.” Tossing out a few more packs of Lucky Strikes and handing lighters to his senior officers, Montgomery waved with both hands and gestured to the driver to move on in search of others to kindle. The men barked and bayed and doffed their soup bowl helmets. He knew they would.

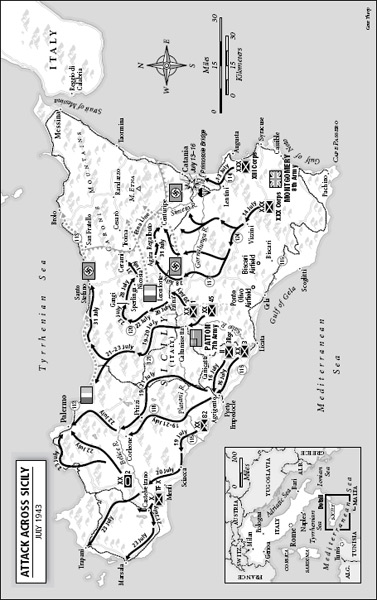

If the campaign against the Axis was going well enough, a new front had opened between the British and the Americans; this battle had already hindered the struggle for Sicily and would impinge on Allied amity for the rest of the war. Montgomery was in the middle of the brouhaha, of course: on Tuesday, July 13, the Eighth Army commander had unilaterally ordered his

troops to cut across Patton’s front and into the American sector on Highway 124, a vital route that ran westward from Syracuse through Vizzini toward the central Sicilian crossroads town of Enna. Axis resistance had begun to clot south of Catania, so Montgomery chose to divide his army, with one corps butting north along the coast, and another looping west around Mount Etna via Highway 124.

Montgomery presented this maneuver as a fait accompli to General Harold R.L.G. Alexander, the senior ground commander for

HUSKY

and Eisenhower’s British deputy, even though U.S. troops stood within half a mile of the highway and were much nearer to Enna than the British. Alexander accepted the impetuous deed without demur, and late Tuesday night he instructed Patton to get out of the way: “Operations for the immediate future will be Eighth Army to continue on two axes.” Eisenhower declined to review the issue, much less intervene. Offering Eisenhower criticism of the British, General Lucas observed, “is like talking to a man about his wife.”

Baleful consequences followed. Only two roads, hugging the island’s east and north coasts, led to the ultimate prize of Messina, and the British now claimed both. Had the Yanks seized Enna by Friday, July 16, they might have severed the main escape route for Axis forces hurrying from western Sicily toward the bridgehead now forming on Mount Etna’s flanks. Instead, Patton’s army would be relegated to the role of flank guard for the British. The 45th Division began trudging back to the beach for a shift to the west, and Omar Bradley scrambled to regroup his corps engineer, medical, ordnance, quartermaster, and signal units. Montgomery now was driving on divergent axes toward objectives forty-five miles apart—coastal Catania and inland Enna—with half his army trundling into poor tank country beyond support of the Royal Navy. Any hope for a quick Allied triumph had vanished, as soon became evident to every man with a map.

The Americans were furious. “My God,” Bradley told Patton, “you can’t allow him to do that.” But stung by Eisenhower’s rebuke aboard

Monrovia

and reluctant to raise Cain after the paratrooper debacle, Patton remained docile, confining his anger to a slashing diary entry—“What fools we are”—and muttering private imprecations: “Tell Montgomery to stay out of my way or I’ll drive those Krauts right up his ass.” An enraged Bradley later declared the pilferage of Highway 124 “the most arrogant, egotistical, selfish and dangerous move in the whole of combined operations in World War II.” The British move “tends to sell us down the river,” Patton’s deputy, Major General Geoffrey Keyes, wrote in his diary.

Beyond any tactical impact, the episode inflamed chauvinistic tensions in the British and American camps. “The feeling of discord lurking be

tween the two countries…has increased rather than decreased,” Harry Butcher had noted after the Tunisian victory. “It is disheartening and disconcerting.” Alexander, for one, remained imprinted with the disagreeable image of fleeing U.S. troops during the Kasserine Pass rout six months earlier; like Montgomery and many British officers, he harbored a supercilious disdain for American fighting qualities. Yank resentment at that hauteur fueled the anglophobia afflicting the American high command. Patton already believed that Eisenhower was “a pro-British straw man” and that “allies must fight in separate theaters or they will hate each other more than they do the enemy.” Now attitudes hardened, and mistrust threatened to mutate into enmity. “At great expense to ourselves we are saving the British empire,” Lucas complained, “and they aren’t even grateful.” Another American general suggested celebrating each July 4 “as our only defeat of the British. We haven’t had much luck since.”

“What a headache, what a bore, what a bounder he must be to those on roughly the same level in the service,” a BBC reporter wrote of Montgomery. “And at the same time what a great man he is as a leader of troops.” That contradiction would define Montgomery through Sicily and beyond, confounding his admirers and infuriating his detractors. “A simple, forthright man who angered people needlessly,” his biographer Alan Moorehead concluded. “At times a real spark of genius…but [he] was never on an even plane.” Even the official British history of the Mediterranean war would acknowledge his “arrogance, bumptiousness, ungenerosity…[and] schoolboy humour.” American disdain for Montgomery tended toward dismissive condemnation: “a son of a bitch,” declared Beetle Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff. His British colleagues, whose scorn at times ran even deeper, at least tried to parse his solipsism. “Small, alert, tense,” said Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, “rather like an intelligent terrier who might bite at any moment.” Montgomery so irritated Andrew Cunningham—“he seems to think that all he has to do is say what is to be done and everyone will dance to the tune he is piping”—that the admiral would not allow the general’s name to be uttered in his presence. “One must remember,” another British commander said of Montgomery, “that he is not quite a gentleman.”

That he had been raised in wild, remote Tasmania explained much to many. Son of a meek Anglican bishop and a harridan mother who conveyed her love with a cane, Montgomery emerged from childhood as “the bad boy of the family,” who at Sandhurst severely burned a fellow cadet by setting fire to his shirttail. “I do not want to portray him as a lovable character,” his older brother said, “because he isn’t.” Mentioned in dispatches six times on the Western Front, he carried from World War I the habits of

meticulous preparation, reliance on firepower, and a conception of his soldiers “not as warriors itching to get into action, which they were not, but as a workforce doing an unpleasant but necessary job,” in the words of the historian Michael Howard. He also accumulated various tics and prejudices: a habit of repeating himself; the stilted use of cricket metaphors; an antipathy to cats; a tendency to exaggerate his battlefield progress; “an obsession for always being right”; and the habit of telling his assembled officers, “There will now be an interval of two minutes for coughing. After that there will be no coughing.” No battle captain kept more regular hours. He was awakened with a cup of tea by a manservant at 6:30

A.M

. and bedtime in his trailer—captured from an Italian field marshal in Tunisia—came promptly at 9:30

P.M

.

In Africa he had seen both glory, at El Alamein, and glory’s ephemerality, in the tedious slog through Tunisia. Montgomery much preferred the former. Now the empire’s most celebrated soldier, he received sacks of fan mail, including at least nine marriage proposals, lucky charms ranging from coins to white heather, and execrable odes to his pluck. Professing to disdain such adulation, he had a talent for “backing into the limelight,” as one observer remarked. On leave in London after Tunis fell, still wearing his beret and desert kit, he checked into Claridge’s under the thin pseudonym of “Colonel Lennox,” then took repeated bows from his box seat at a musical comedy as ecstatic theatergoers clapped and clapped and clapped. “His love of publicity is a disease, like alcoholism or taking drugs,” said General Ismay, Churchill’s chief of staff, “and it sends him equally mad.”

Success in snatching Highway 124 would encourage Montgomery to disregard both peers and superiors, especially the indulgent Alexander. “I do not think Alex is sufficiently strong and rough with him,” General Brooke wrote of Montgomery in his diary, adding, “The Americans do not like him and it will always be a difficult matter to have him fighting in close proximity to them.” If audacious among allies, Montgomery became ever more cautious with adversaries. “The scope of operations must be limited to what is practicable,” he advised John Gunther in Sicily. “The general must refuse to be rushed.” Still, his own men cherished his ability to convince them “to believe in their task, to believe in themselves, and to believe in their leader.” Sailing about in the big command car, he stopped to ask a Canadian unit, “Do you know why I never have defeats?”

Well, I will tell you. My reputation as a great general means too much to me…. You can’t be a great general and have defeats…. So you can be quite sure any time I commit you to battle you are bound to win.

In a printed broadside to Eighth Army he asserted that thanks to “the Lord Mighty in Battle,” the enemy had been “hemmed in” on the northeast corner of Sicily. “Now let us get on with the job,” Montgomery urged. “Into battle with stout hearts.” To Brooke in London he later added, “All goes well here…. We have won the battle.”

Neither assertion was true. On the third day of the invasion, Field Marshal Kesselring had arrived in Sicily from Frascati, and while wistfully abandoning hopes of flinging the Anglo-Americans into the sea, he soon began to reinforce the two German divisions on the island with two more, the 29th Panzer Grenadiers and the 1st Parachute Division. Thousands of Axis troops in western Sicily also hied east; Kesselring recognized that a stout bastion could be built around Etna’s slopes, either to hold the Messina Peninsula indefinitely or at least to keep open the main escape route to mainland Italy. The task now was “to win time and defend,” even though tension and misery gnawed at soldiers who feared being trapped on Sicily as so many comrades had been trapped in Tunisia. German attempts to commandeer Italian military vehicles led to internecine gunplay, with two Italians and seven Germans killed in one three-hour firefight. Still, Kesselring radiated his usual bonny optimism. As soldiers dug hasty fortifications along the Simeto River south of Catania, an elderly Italian nun dished out food and Holy Virgin medals.

Montgomery had expected the Catanian plain beyond Augusta to provide a flat alley for his armor, much as the desert had. Instead, he found “a hole-and-corner area, full of lurking places,” in one soldier’s description, with irrigation ditches and stone farmhouses perfect for concealing antitank weapons. “This is

not

tank country,” a British officer lamented. Another Tommy complained that Sicily was “worse than the fuckin’ desert in every fuckin’ way.”

Eighth Army’s attempt to break through along the coast was first checked by yet another airborne fiasco, a mission patched together on short notice to seize the Primosole Bridge, seven miles south of Catania. Paratroopers and glider infantry on the night of July 13–14 ran into the now familiar hellfire from confused Allied ships, some of which mistook cargo racks on the aircraft bellies for torpedoes. Those managing to reach the coast met sheets of Axis antiaircraft fire. Fourteen planes were lost, a couple of dozen turned back to Tunisia without dropping, and 40 percent of the surviving planes suffered damage. By mischance, German paratroopers also jumped at the same time on adjacent drop zones. “One shouted for comrades and was answered in German,” a paratrooper recalled. Of nearly two thousand men in the British parachute brigade, only two hundred

reached the bridge, which they held with a few reinforcements for half a day until being driven off. By the time Tommies recaptured the bridge at dawn on Friday, July 16, the Germans had cobbled together a defensive belt just to the north that would halt Eighth Army for a fortnight. “It was yet another humiliating disaster for airborne forces,” said Lieutenant Colonel John Frost, a much decorated battalion commander, “and almost enough to destroy even the most ardent believer’s faith.”

The XXX Corps, dispatched by Montgomery to the northwest on Highway 124, hardly fared better. Here hills were stacked on more hills in a Sicilian badlands, and hill fighting never suited Eighth Army: Montgomery “seemed to mislay his genius when he met a mountain,” his biographer Ronald Lewin observed. The terrain’s constricted visibility “makes for general untidiness,” a British officer complained, and exposure to the July sun “is like being struck on the head.” Every road and goat path was mined; soldiers perched like hood ornaments above the front bumpers of their creeping vehicles, scrutinizing the track for telltale disturbances. Artillery crashed and heaved, day and night. “We break the farmer’s walls, trample his crops, steal his horses and carts, demand fruit and wine,” a soldier wrote in his diary. “If he is unlucky he gets his home smashed by shells, his crops devoured by fire.” Canadian troops howled with outrage upon finding their dead disinterred and robbed of their boots. Refugees desperate for meat could be seen wrapping dead dogs in butcher paper.