The Day of Battle (99 page)

Authors: Rick Atkinson

Tags: #General, #Europe, #Military, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War, #World War II, #World War; 1939-1945, #Campaigns, #Italy

Outside Valmontone ranks of dead American soldiers lay within the garden walls of a Franciscan convent transformed into a mortuary. “Over

each one of them we placed a blanket under which stuck out the shoes in the sun, giving the impression of being extremely large,” an Italian witness later recalled. German snipers popped away across hill and dale. When a GI abruptly pitched over, a tanker yelled to a crouching rifleman, “Is he hurt bad?” The rifleman shook his head. “No, he ain’t hurt. He’s dead.”

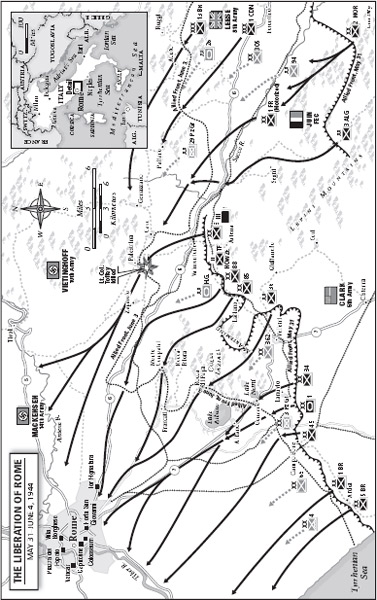

Clark took nothing for granted, even as the breakthrough on Monte Artemisio “caused all of us to turn handsprings.” Ubiquitous and intense, aware of the imminent invasion at Normandy, he lashed the troops with unsparing urgency. Eleven of his divisions pounded north along five trunk roads that converged on Rome from the lower boot. Alexander on Friday, June 2, shifted the interarmy boundary north of Highway 6 to give Fifth Army—now 369,000 strong—a wider attack corridor. General Harding, Alexander’s chief of staff, phoned Gruenther with effusive praise. “He stated it with such a sincere tone that I am certain he meant what he said,” Gruenther told Clark. “For my part I am throwing my hat in the air and yelling, ‘Hip, hip, hooray.’”

Clark’s peaked cap remained on his head. “I’m disappointed in the 45th and 34th today. They’ve not gotten anyplace,” he told Don Carleton in a call to VI Corps early Friday evening.

“They got a lot of prisoners and killed a lot of Germans,” Carleton replied.

“But they haven’t

gone

any place,” Clark said. “I want to take ground.”

With casualties climbing and Harmon’s 1st Armored Division losing over two hundred tanks in eight days, Clark fretted that another delay likely meant waiting for Eighth Army “to get into the act.” Indeed, Alexander on Friday night privately mused that if Clark failed to finish routing the enemy within forty-eight hours, “we shall have to stage a combined attack by both Fifth and Eighth armies when the latter gets up.” Even Clark’s mother urged alacrity. “Please take Rome soon,” she wrote her son from Washington. “I’m all frazzled out.”

He was trying, driven by dreams of glory undimmed and unshared. When Alexander’s headquarters proposed a communiqué that would read, “Rome is now in Allied hands,” Clark told Gruenther, “They carefully avoid the use of ‘Fifth Army,’ and say ‘Allies.’ You call Harding immediately. Tell him I don’t agree to this paper.” Churchill renewed his plea for shared Anglo-American honors. “I hope that British as well as Americans will enter the city simultaneously,” the prime minister had written Alexander on Tuesday. But few Tommies could be found in the Fifth Army vanguard. When Alexander proposed that a Polish contingent join the spearhead into Rome as a tribute to their valor at Monte Cassino and in acknowledgment of their Roman Catholicism, Clark ignored the suggestion.

“The attack today must be pushed to its limit,” he told Truscott on Friday. Only to his diary did Clark confide, “This is a race against time, with my subordinates failing to realize how close the decision will be.”

Valmontone was found abandoned on Friday, at last. “No contact with enemy anywhere along the front,” the 3rd Division reported. A reconnaissance battalion crept up Highway 6, and by dawn on Saturday, June 3, Truscott’s VI Corps and Keyes’s II Corps were poised for a bragging-rights race into Rome from the south and southeast, respectively. Roving Italian barbers gave haircuts and shaves to unkempt soldiers keen to look groomed for the liberation.

Like Gruenther’s tossed hat, the tonsorial primping was premature. German rearguard panzers lurked in the shadows to ambush the incautious. Fearful of a counterattack from the east that could sever the new Fifth Army supply route on Highway 6, Lieutenant Colonel Jack Toffey led two depleted 7th Infantry battalions into the rolling meadows below Palestrina, an ancient Etruscan town famous for its roses and said to have been founded by Ulysses. Early Saturday morning Toffey informed the regimental command post of a troublesome Tiger tank, “hull down in a road cut.” Later in the day, as Palestrina’s cyclopean walls hove into view, he reported seeing outriders from Juin’s FEC on his flank.

That would be his last dispatch. At 2:14

P.M

., a radio message to the regiment reported that Colonel Toffey had been wounded half a mile below Palestrina. After climbing to the second floor of a tile-roof farmhouse for a better view of German positions, Toffey was sitting on the floor with a radio between his knees when a tank round slammed into the upper story. At least one officer believed the shell came from a disoriented Sherman tank crew a few hundred feet behind the farmhouse; others insisted the round was German. Regardless, dust filled the dismembered room as Toffey lay sprawled against the front wall with a shell fragment in the back of his head. “His eyes were open but seeing nothing,” an officer noted. At 2:40

P.M

., a radio report to the command post announced his death. A lieutenant and three enlisted men had also been killed, and a tank battalion commander badly wounded.

Veiled with a blanket, Toffey’s mortal remains were laid on a stretcher and driven by jeep to the rear. Since landing on the beaches of Morocco nineteen months earlier, he had fought as faithfully as any battle commander in the U.S. Army. Now his war was over, his hour spent. A short time later, Juin’s troops relieved the 7th Infantry, which would not fight in Italy again. The 3rd Division history lamented the passing of “a mad, genial Irishman,” among “the best-loved and most colorful characters in the division, if not our entire Army.” One comrade wrote that “there will never be

his like again,” but that was incorrect: the country had produced enough of his ilk to finish the war Jack Toffey had helped win.

Upon learning of Toffey’s death, Clark ordered Gruenther to draft a list of midlevel officers with long, sterling battle records who would be the generals in America’s next war. “I am sending them home because they are too valuable to risk in further combat,” Clark wrote.

For Toffey the gesture came too late. In a note to General McNair in Washington, a grieving Truscott called him “one of the finest officers I have ever known.” But the most poignant epitaph came from a former comrade in the 15th Infantry: “Perhaps he was kept overseas a little longer than his odds allowed.”

Even before the American thrust across Monte Artemisio, Albert Kesselring doubted whether the indefensible terrain below the Tiber River could be held much longer. Of 540 German antitank guns in Italy, 120 remained. On June 2, he advised Berlin that in three weeks his armies had suffered 38,000 casualties; among his divisions still fighting, only two were even 50 percent combat effective. Charred tanks and trucks fouled every road and cart path. The Subiaco Pass, through which much of Vietinghoff’s Tenth Army would squeeze, resembled “a huge snake of burning vehicles.”

Vietinghoff himself was a casualty: sick and spent, he handed command to his chief of staff and stumbled off to a hospital in northern Italy. A few hours later, Kesselring’s own staff chief, Siegfried Westphal, collapsed from nervous exhaustion. Mackensen, too, was finished: Hitler approved Kesselring’s demand that he be cashiered as Fourteenth Army commander for incompetence in defending the Colli Laziali, among other alleged failings.

Kesselring had earlier proposed a scorched-earth retreat that included the demolition of all Tiber River bridges, as well as power, rail, and industrial facilities around Rome. Hitler demurred. Roman bridges had “considerable historical and artistic merit”; moreover, the capital held little strategic value, and leaving it in ashes would merely enhance Allied political and propoganda gains. On June 3, less than two hours after Jack Toffey’s death, the high command informed Kesselring: “Führer decision. There must not be a battle of Rome.”

Rear guards would continue to harass the American horde in the Roman suburbs, buying time for the garrison to flee from what Berlin now declared to be an open city. Fourteenth and Tenth Army troops would hasten north, in small bands if necessary. A radio code word—

ELEFANTE

—warned that Allied forces were closing in on the capital.

The sound of gunfire from the Colli Laziali had been audible since May 29, and unease among the German occupiers in Rome now gave way to

panic. Papers were burned, granaries fired; an ammunition dump in the Campo Verano cemetery was blown up, along with a barracks, a Fiat plant, a phone center. The white peacocks strutting about the German embassy garden had long been shot and roasted. The Hotel de la Ville in the Via Sistina, a pleasant redoubt known as “Brighter Berlin,” emptied out. Near the Piazza Fiume, soldiers methodically looted a hardware shop, packing their booty into a covered truck. Officers living the high life on the Via Veneto pilfered the silverware and water goblets before decamping.

“Germans streaming through the city, pushing carts, trying to swipe cars, marching on foot,” Peter Tompkins, the OSS operative, wrote in his diary. “The cafés were still open and doing big business.” A six

P.M

. curfew was imposed, “but it isn’t quite clear who is giving the orders.” Tompkins filled his bathtub just before the city’s water pipes ran dry. As Romans watched from behind shuttered windows, convoys streamed out of the city, vehicles three and four abreast on the Via Cassia, the Via Salaria, and abutting sidewalks. “Wild-eyed, unshaven, unkempt, on foot, in stolen cars, in horsedrawn vehicles, even in carts belonging to the street cleaning department,” one witness reported. “Some of them dragged small ambulances with wounded in them.” Fascist Blackshirts pleaded for rides or trotted north, furtively looking over their shoulders. Tompkins, the dutiful spy, recorded it all: Germans fleeing on bicycles, Germans hobbling on crutches, Germans on motorcycles with flat tires, Germans near the Piazza Venezia “trying to get away with cars that no longer have

any

tires, driving on the rims.”

And in the Gestapo cells beneath Via Tasso 155, prisoners cocked an ear to the distant grumble of Allied guns. In hushed whispers, eyes agleam, they debated with urgent intensity the variables of ballistics and wind direction, trying to gauge just how far away their liberators might be.

Not far. Eleven months after the Allies first waded ashore in Sicily, the titanic battles between army groups that characterized the Italian campaign now subsided into niggling suburban gunfights between small bands of pursuers and pursued. Seventeen major bridges spanned the Tiber along an eight-mile stretch, linking eastern Rome not only to Vatican City and the capital’s west bank but also to the highways vital to Fifth Army’s pursuit up the peninsula to the northwest. Flying columns of tanks, engineers, and infantrymen began to coalesce with orders to thrust through the city and secure the crossings.

“Looks as if the Boche is pulling out, and [Truscott] wants you to get up there and seize the crossings over the Tiber as fast as you can,” Carleton told Ernie Harmon early Saturday afternoon. “Make all the speed you

can.” A few hundred feet above Highway 6, Keyes from his observation plane dropped a penciled message to the armored task force led by Colonel Howze: “Get those tanks moving!” Howze put the spurs to his men, only to blunder into yet another chain of ambushes. “In a few minutes the lead tank would stop and burst into flames,” Howze later wrote, forcing the cavalcade to idle until the enemy blockages could be out-flanked and routed.

Such petty inconveniences hardly diminished the swelling euphoria. “The command post has gone to hell,” Gruenther radioed Clark from Caserta at 4:15

P.M

. on Saturday. “No one is doing any work here this afternoon. All semblance of discipline has broken down.” According to II Corps intelligence reports, Germans were withdrawing “in such confusion and speed that their retreat has assumed proportions of a rout.” Clark sternly reminded his lieutenants to keep killing. “Your orders are to destroy the enemy facing Fifth Army,” he told the corps commanders shortly before five

P.M

. “Rome and the advance northward will come later.”

Precisely who first crossed Rome’s city limits early on Sunday, June 4, would be disputed for decades. Various units claimed the honor by filing affidavits and issuing proclamations and protests. An 88th Division reconnaissance troop and Frederick’s 1st Special Service Force, which had been merged with Howze’s task force, had the strongest claims, but Clark subsequently wrote that “it is impossible to determine with certainty the unit of the Fifth Army whose elements first entered the city.” Patrols darted into the city only to be driven out by scalding gunfire. German paratroopers holding a strongpoint at Centocelle, just east of Rome, knocked out five American tanks before slipping away. On Highway 6 near Tor Pignatara, an antitank gun shattered two more Shermans, then vanished into a warren of alleys.

Traffic jams and friendly fire, orders and counterorders, flocking journalists and even a wedding party—the bride, dressed in gray and holding a rose bouquet, tiptoed around German corpses in the roadway—threatened to turn the liberation into opera buffa. Clark left Anzio in brilliant sunshine at 8:30

A.M

. with a convoy of two armored cars and six jeeps packed with more journalists. Arriving at Centocelle, he hopped from his jeep in a flurry of salutes. When Clark asked why the drive had stalled, Frederick replied, “I’m holding off the artillery because of the civilians.”