The Day the Falls Stood Still (10 page)

Read The Day the Falls Stood Still Online

Authors: Cathy Marie Buchanan

Tags: #Rich people, #Domestic fiction, #World War; 1914-1918, #Hydroelectric power plants, #Niagara Falls (Ont.)

“Do you know about the Boundary Waters Treaty?”

“Yes.” Over the years I had heard Father grumble about the treaty that limited the water diverted from the river for hydroelectricity to about a quarter of the natural flow. “Sheer idiocy,” he would say. “You can’t tell me we shouldn’t be allowed a little more when the river’s high in the spring. And who cares how much is going over the brink in the middle of the night?”

“Near as I can figure,” Tom says, “with the powerhouses already on the river taking what they’re allowed, there’s not enough left for the hundred thousand horsepower Beck is talking about.”

“My father says Beck’s a genius at having things turn out his way.”

“Beck’s a self-promoting industrialist who doesn’t give two hoots about destroying the river.” Tom blows out though closed lips, then catches himself—fortunately—and shifts to a softer tone. “I just hope the Boundary Waters Treaty isn’t as easy to ignore as the Burton Act.”

The Burton Act, the first piece of legislation meant to preserve Niagara Falls, was quietly swept aside a half dozen years ago in favor of the more lenient Boundary Waters Treaty. “History isn’t on your side,” I say.

Once we have crossed to the American side, the railbed descends to just a few feet above the water, and he says, “My grandfather used to say we were going back in time when we went into the gorge.”

I cock my head, perplexed.

“Look at the bands in the wall. We’re heading down to the oldest layers.”

My gaze moves across strata of gray, pale beige, pink-brown, some jagged, others worn smooth. At the base of the walls, the river writhes and bucks in response to the narrowed gorge. “Just wait,” he says. “At the Whirlpool Rapids, the waves are thirty feet high. It’s where Captain Webb died.”

It is part of the lore the locals gather as children: Captain Matthew Webb coming to Niagara to swim the rapids some thirty years ago, fresh from being the first to conquer the English Channel. It took four days for his body to surface, and when it did there was a three-inch gash in his temple. Like that of the Maid of the Mist and her canoe, like that of Blondin and his tightrope, like that of Annie Taylor and her barrel, it is a story I have heard more times than I can count. “He was a fool,” I say.

“My grandfather told him that.”

“Your grandfather knew Captain Webb?”

“He showed up one morning, asking my grandfather for his opinion on swimming the rapids. My grandfather told him drowning takes a few minutes, that he wouldn’t last long enough for that.”

“Why your grandfather?”

“Everyone knew he was the fellow to talk to about the river,” he says.

I am sitting very still, thinking hard, because I am on the cusp of dredging up some bit of lore, something the children in Niagara Falls are told as they are tucked into beds. It is a story Father had handed down to me, something about a fellow—a giant with shoulders that filled a doorway and hands the size of pie plates when he spread his fingers wide—who had come to Niagara Falls from the north and lived out his days in a cabin overlooking the gorge, always an eye on the river, always predictions being made, always the predictions coming true.

“Was he a giant?” I blurt it out.

“That’s what some folks say.”

“He came from the north.”

“His name was Fergus, and he’d been logging in the wilderness.”

“He walked all the way here.” I can almost hear Father, stretched out on his back, me in the crook of his arm, spinning the tale of Fergus Cole: After growing tired of salt pork and molasses, baked beans and tea, bunkhouses smelling of tar paper, tobacco, and drying socks, he started walking south, and kept walking until he hit Toronto. He stayed for only a few months before the squalor and the din of city life pushed him around the western curve of Lake Ontario and onward to the mouth of the Niagara. He walked alongside the river, over the plains beneath the escarpment, and then up the escarpment itself. The last leg of his journey ought to have been easy going; there was a decent road. But he left it and made his way through the forest thick with pine, spruce, cedar, and oak along the rim of the gorge, not stopping until he reached the Horseshoe and American falls.

“My father used to tell me about Fergus. I know about the tar paper and the drying socks.”

“Tar paper?” He laughs.

“I know about the day the falls stood still. He told me about that,” I say, picturing Father’s giant dragging the last of the stragglers by the scruffs of their necks from the muddy bed of the upper river.

“It was the first of his predictions,” Tom says. “The first of his rescues.”

“Father always says it was the river’s way of letting the town know Fergus Cole had arrived.”

“I can’t believe you know all this stuff.” It is plain to see he is pleased.

“Everyone does.”

Then, as we round Whirlpool Point, he points toward the Lower Steel Arch Bridge and says, “That’s where Ellet built his bridge, the first to cross the gorge.”

“Wasn’t he the fellow who hung an iron basket from a cable strung across the gorge?”

“He charged tourists a dollar for a ride. Fergus worked on the bridge as a carpenter for a bit. It made him furious, people dangling in a basket meant for moving workmen and supplies.”

From the trolley car I have a clear view of the river’s boiling fury. It is easy to imagine the tourists suspended up above, daring to look down, peeking between gloved fingers, laughing to show their nerve. As I scan the height of the gorge walls, the story of Father’s giant using the basket and a ladder to reach a group of stranded workmen comes to me. “There was a wind squall. It was your grandfather who rescued the men.”

“He quit after that,” Tom says. “He said the squall was a warning.”

“Is that what you think?”

He is quiet a moment, then shrugs. “No one should mock the river.”

“I think it would have been God that sent the wind, not the river.”

“Maybe either way is one and the same.”

I am thinking of Father, wondering if he knows it is the grandson of Fergus Cole pouring his drinks at the Windsor Hotel. “Fergus taught you about the river, then?” I say.

He nods. “We lived in a cabin at Colt’s Point. The gorge was right there. It’s what we did: hike down to the river, set a few snares, catch a few fish. Once we pulled a fawn from the forebay of a powerhouse, and my grandmother let me keep it in the summer kitchen right the winter through.”

“I remember my father saying the constables were always on your doorstep, asking for help.”

“They’d show up if a tourist or a boy or a fisherman was late,” he says, smiling at the thought of it. “Fergus always took me along. I don’t remember not knowing about eddies and undercurrents and standing waves.”

“What about your grandmother?”

“Sadie.”

And then I cajole and prod and piece together the details he gives me. Sadie was a woman who knew that groundnut root would pass for yam once it was peeled and boiled. She knew it could be ground into flour to make a fine loaf. She cured Fergus of the warts that had plagued him since his days felling trees in wet socks. A drop of orange-red sap from bloodroot smeared between the toes twice a day. The minute Tom sniffled, she handed him a cup of pine needle tea. The minute he coughed, it was a tincture of honey and boiled white pine bark.

“I’m sorry I won’t meet them,” I say and hear the implication, that I would have been introduced had they still been alive. And while I spoke the words sincerely, the seriousness of the idea gives me pause. I want to take back my words.

He turns to me and says, “Fergus had just barely gotten the news the Burton Act was passed when he died. Sadie paid a boy, and he brought the newspaper every day. She’d flip through the pages, and then one day she said the act had been passed. By then I was on the mend and sitting up in the bed she’d set up beside his. When she was gone he said, “It’s good news. There’ll be something left for my great-grandchildren.’ It was the most he’d said in a week, and he had a fit of coughing. Then Sadie was back, stroking his forehead and telling him to take a deep breath. They were his last words.”

I fidget with a button, face straight ahead, the best I can do to give him a bit of privacy, and try to ignore the way his voice cracked, his halted breath. And then a moment later, almost certain it is not usual for him to speak so openly, I am wondering if he might be thinking of me as someone he has been waiting for and feeling uneasy about my part in fostering the idea if I am right.

We are a short ways from the Lower Steel Arch Bridge when he leans from the trolley and tilts his face upward, scanning the wall of the gorge. “It’s cooled off,” he says. “I don’t like being in the gorge when the temperature drops.”

“It’s still pleasant enough.”

“Bess,” he says, shifting his weight to his feet, “we’d better get off.”

“Here?”

“We can follow the tracks to the rim and catch the next trolley up top.”

The railbed is several yards across with a few feet clearance between the track and the gorge wall and, on the opposite side, a steeply sloping riverbank.

“We’d better hurry,” he says, grasping my upper arm and steering me toward the open side of the car while several fellow passengers turn their heads to watch.

“You want me to jump?” I am poised at the opening, the brush alongside the track rushing by my feet, when I first hear what begins as a low rumble and ends seconds later as a resounding crash. A cloud of gray dust rises from the railbed a dozen yards ahead. Passengers scream and leap from the sides of the car as the trolley slows to a stop. My initial instinct is to join them. But a greater instinct wins out and I remain beside Tom, his hand firmly on my arm. A moment later he is telling me to stay put and leaping from the trolley and then running up alongside it. “It’s safe,” he yells. “You’re all safe.”

Passengers turn to him. He nods. “No more rock will fall.”

“I’ve sprained my ankle,” a woman says and flops onto the grass beside the track.

“You nearly trampled me to death,” another woman says to a man with his hand on her elbow in a proprietary way.

“I’ll sue,” a second man says.

“Have you got a crowbar?” Tom hollers up to the conductor. “It isn’t much of a slide. We can clear it ourselves.”

“We’d better wait for the authorities,” says the man who said he would sue.

“You can wait all you like,” another man says.

Tom makes his way back to me. “Are you okay for a bit?”

“I’m fine.”

Then he is off. He takes the crowbar from the conductor as he passes and a moment later is tipping fallen rocks into the river. Soon enough, a handful of men follow him and begin helping out.

I wait in the trolley, watching, noticing the way the men defer to him. Which rock should be moved next? Should the rubble at the base of the wall be left to shore it up? They see his comfort with the work, his certainty that the wall above will hold. And he is easily the strongest among them, the one to whom the crowbar is passed each time a particularly large rock is exposed.

When I am nearly to the fallen rock, he hands off the crowbar and lopes toward me. “What is it?” he says.

“How did you know?”

“Know what?”

“You knew we were in for a slide,” I say.

“I was pretty sure.” He slips his hands into the pockets of his trousers.

“But how?”

“There were crevices but no scrub. Crevices without enough soil for a bit of scrub are new and need to be watched. And the temperature dropped.”

“And water in cracks expands and contracts.”

Then he speaks almost shyly, as though he is not sure I want to hear: “There’s something more, too. There are moments, usually on the river. It’s nothing I know how to explain.”

I watch him, filling with wonder. I have heard Father argue that intuition is entirely rational. There is no mystery, no magic, nothing astonishing as far as he is concerned. A woman knows her child is ill, even before laying her palm on his forehead, only because he slept late and called out in the night and ate poorly the evening before. It does not matter one iota that she cannot articulate the clues. Father would say, “We do not always know what we know.”

But I am not so quick to rule out mystery and magic. I like the astonishing and do not doubt that it exists. What is God, after all, if not mystery and magic, and astonishing? I have little inclination to scoff at Tom’s bit of mystery. From my window seat at the academy, I saw prayers in the rising mist.

I want to hear more, but men are glancing over, waiting, uncertain what to do next. I nod so he will know I have understood.

“I should get to work,” he says.

As I make my way back to the trolley, I am determined to contribute in some small way. When I reach the woman with the sprain, I tear a strip of fabric from the hem of my underskirt and bind her swollen ankle with it. As I help her to her feet, she says, “You make a handsome pair,” and I smile.

Once the woman is hobbling about, her arm looped through that of a fellow in a uniform who seems to be her husband, I occupy several children with a game of I Spy, my attention often shifting to Tom. A girl of about twelve cups her hand around my ear and whispers, “Is he your beau?”

I cup my hand around her ear and whisper back, “Yes.”

I will feel Tom’s lips on mine today. I know it for sure. I know it because if he does not lean toward me, offering his mouth, I will lean toward him, offering mine, the Windsor Hotel pushed from my thoughts.

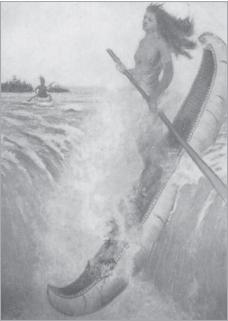

The legend of the Maid of the Mist

Niagara Falls (Ontario) Public Library.

I

have been made an offer of marriage. As the proposal was stammered out, I had the strangest sensation, as though I were watching one of those scenes in a play that causes the audience to snicker in their seats. A young actor announces he is heartbroken or, alternately, deeply in love. In either case, friends and relations of the lovesick fellow express condolences or congratulations, whichever is appropriate. All the while their minds are searching for some tidbit of missed information that will let them in on just who the coveted female is.

What a dreadful episode, Edward proposing to me.

Not five minutes ago, he went down on bended knee, and took my hand in his, at which point I became momentarily dumb, my tongue thick and dry. I was sitting on the chaise on the veranda, uncomfortable though I had forgone a corset. The dress was Mother’s, made acceptable enough by the addition of a ruffle of itchy tulle at the neckline. Isabel had been called inside, ostensibly to help prepare tea, but had been gone twenty minutes or more when Edward dropped to his knee.

I was half-listening to him ramble on about how well wicker furniture was selling in spite of the war when next thing I knew he was on his knee, his head bowed, unable to meet my eye. “Will you marry me?” he said.

Silence ensued while I tried to regain the use of my tongue. “Edward?”

He cleared his throat and, a little louder, said, “Will you marry me?”

“Are you serious?”

He looked at me. Seriously.

“But I’m only seventeen,” I said. Until I turned eighteen, marriage was impossible, unless my father gave his consent.

“I’ve already asked and your father has agreed.”

“Oh.”

He looked up. “Kit said not to expect an answer right away.”

“I’m so surprised. And flattered, but, Edward, I…”

“I could help you, your family,” he said.

My hand flew to my hip. “Did Kit tell you that?”

“Are you angry?”

“Did she put you up to this?”

“No,” he said.

Suddenly Isabel and Mother were on the veranda with the tea.

Isabel’s eyes went to Edward, kneeling beside the chaise.

“A button fell off his shirt,” I said.

As she peered under the chaise, I said, “I think it rolled through a crack.”

“I have a box of spare buttons upstairs,” Mother said, although she could see just as well as Isabel that no button was missing from his shirt.

He stood up from kneeling, and I waited for him to say, “Button? What button? Did a button fall off my shirt?” But for once his eyes glinted comprehension. “There are plenty of buttons at home,” he said. He tipped his Panama hat to Mother and Isabel, and then to me. “I’ll be off.” Rude or not, he meant to escape before tea was served.

I stood up from the chaise and stepped toward him, already heading for the Runabout. Isabel and Mother remained on the veranda, Mother’s arm firmly looped through Isabel’s. When we were midway to the automobile, Mother and Isabel called out their good-byes and disappeared into the house, likely to tend to some newly urgent housekeeping task.

At the Runabout, he said, “I’ll be in touch.” He leaned toward me and delivered a dry, papery kiss to my cheek.

I

sit on the chaise, forehead in my hands, elbows on my knees. Edward has never kissed me before, and I wonder what, if anything, invited the kiss. Was it because I did not reject his proposal flat out? Or because we conspired about the lost button? Was it that he had read too much into my tidy hair and itchy dress? While logic says the kiss would have come, invited or not, I am riddled with guilt.

As a first kiss, Edward’s effort would have been a great disappointment, a kick in the teeth really, given the imaginings of my girlhood and the secrets whispered in the Loretto corridors. But because it was not the first, it merely provided proof that nothing more than friendship exists between Edward and me.

When Tom kissed me at the close of our afternoon circuiting the gorge, I did not purse my lips. They fell slightly open, entirely receptive to the warm breath and wet of his mouth. The kiss lasted only seconds; we were barely hidden in the shadows of the Lower Steel Arch Bridge. Still, I have imagined that kiss a thousand times since. I have imagined his tongue against mine. Afterward, when we stood looking at each other, my flesh was taut, my skin goose-pimpled, my breath noticeably short, at least until the Coulsons passed by in their Oldsmobile, came to a halt, and insisted I climb into the backseat.

Before I even had the door pulled shut, Mrs. Coulson twisted around to face me. “Good gracious, Bess,” she said. “Who on earth was that?”

I was trembling under her piercing gaze, hardly able to breathe. “He used to bring us fish.”

“His hand was on your arm.”

I stared down at my knees, thanked God that, when we pulled into Glenview, Mother would not yet be back from Toronto or Father from the Windsor Hotel.

“What about your family?” she said, an angry knot of lines appearing on her brow. “A good connection is what you need.” Mr. Coulson patted her arm, as though to calm her, but she shrugged off his hand. Her voice grew louder. “People gossip, Bess. And there you are, fueling the flames. And that layabout. You were raised better than that.” She was silent as we turned onto Buttrey Street except for the occasional sigh.

At Glenview I said, “I wasn’t doing anything indecent at all,” and willed the tears not to come as I scrambled from the automobile.

Then, it was “You stay away from the likes of him,” quietly hurled from her lips.

T

he screen door claps the wood of the jamb, and I look at Mother, standing there, watching, probably mulling over how best to approach me, particularly if Mrs. Coulson has called, which she very likely has. “Bess?” she says. “May I sit with you?”

I shift to the tall end of the chaise, and she sits at the foot.

“Well?” she says.

“He proposed.”

“It’s wonderful,” she says. “He’s kind and generous. And most of all, he adores you.”

I throw my palms open. “I’m only seventeen.”

She lays a hand on my thigh. “You’re a woman. You’ve shown all of us that this summer,” she says.

“Then I should decide whom I’ll marry.” I mean to thump the chaise with my fist but only let it flop down beside me.

“It is your decision, Bess.”

“But I don’t love him,” I say. I am absolutely sure of it, given Tom, given our kiss.

I am delivered a long, possibly rehearsed lecture, the net of which is that there are two kinds of love. One that is slow in coming and builds with shared kindnesses. And another that is all-consuming, blind, little more than lust. “The first can last a lifetime,” she says. “The second is founded on nothing and cannot.”

I find myself wondering into which camp she and Father fall. They married young and speak fondly of their early days, of the winter Mother’s shoe soles wore through and Father stuffed newspaper into the toes of his boots and gave them to her. But lately she has begun to sigh deeply when his back is turned. Does she regret marrying him? I will not ask. To do so might lend a bit of credence to her words.

“That fellow who brought the fish,” she says and waits, eyes narrowed, head cocked.

“I was out walking on River Road.”

“He has nothing to offer you.”

“I don’t want anything from him.” I smooth damp palms over my skirt, anxious that she somehow knows just how badly I want a second kiss.

“You’ll want a roof over your head, the odd pretty dress, sugar for your tea…”

“And Edward can give me all that so I should marry him?” I stand up from the chaise, walk to the far corner of the veranda, and stand with my back to her.

“He is a gentleman. He’ll devote himself to you.”

I turn toward her. “I know. I know he would, but still.”

“As for the fellow who brought the fish,” she says, and I shrink under her steady gaze. “He brought you to some dark corner of the Lower Steel Arch Bridge. Your reputation was the furthest thing from his mind. He isn’t a gentleman, not in the least.”

“Mrs. Coulson is a busybody.” Brave words from a girl of seventeen with a month’s worth of daydreams under scrutiny and withering.

“He behaved improperly.”

Not feeling altogether well, I sit back down on the chaise and say, “Edward should marry Isabel.”

“He wants to marry you.” She brushes my cheek with the back of her hand.

“What about love growing over time and all that?”

Her gaze leaves mine. “Edward has made up his mind.”

“And so have I,” I say, though my head is a muddled, murky pool. “And I won’t marry him.”

I begin to cry, and she takes me into her arms. My cheek against her breast, she rocks me back and forth, cooing, “You’ll decide for yourself” and “I only want what’s best,” though I have already said I will not marry Edward.

She rubs the place that aches between my shoulder blades and smoothes my hair. I sniffle and bawl, needing that embrace like a child, like a child taking those first few steps toward the safety net of outstretched arms.

If she insisted, or argued even a little bit, I think I might be able to stop the tears, the second guessing. But, wrapped in my mother’s love, I cannot. With each heave of my shoulders, with each gasp for breath, her words gain a smidgen of credibility.

Eventually, I am able to say, “Isabel would hate me if I married Edward.”

She is silent a moment, her hand motionless on my back. Then she gently guides me to sitting upright and tilts my chin so that she can see my face. “Take your time deciding,” she says and wipes my cheeks and nose with her handkerchief. “Isabel will see the upside in having Edward as a brother-in-law.”

She is beautiful just now, her forehead smooth, her eyes bright, brimming with hope.