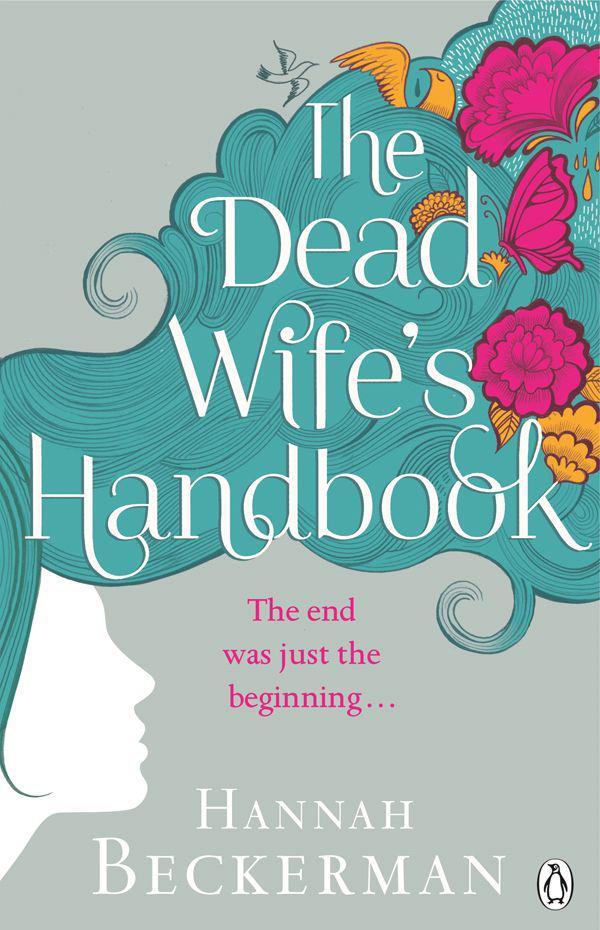

The Dead Wife's Handbook

Read The Dead Wife's Handbook Online

Authors: Hannah Beckerman

Hannah Beckerman

THE DEAD WIFE’S HANDBOOK

Contents

Prologue

SHOCK

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

DENIAL

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

ANGER

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

BARGAINING

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

DEPRESSION

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

TESTING

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

ACCEPTANCE

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Acknowledgements

Follow Penguin

For my mum, Tania,

My husband, Adam,

And my daughter, Aurelia:

Three generations who taught me what love really means

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on; and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

Shakespeare,

The Tempest

Prologue

I didn’t mean to die so young. I don’t suppose anyone does. I don’t suppose many people would willingly fail to reach their thirty-seventh birthday or their eighth wedding anniversary or see out their daughter’s seventh year on the planet. I suspect there aren’t many people who would voluntarily relinquish all that, given the choice.

But that’s the point; we don’t get a choice, do we? One day you’re leaving a restaurant with your husband, conscious of the future only so far as your certainty that it will arrive and you will be part of it, preoccupied with the promotion you’ve just been celebrating and the summer holiday you’ve been planning and the child’s progress you’ve been discussing. An evening when your happiness is due only in part to the bottle of champagne you ordered but is mostly a result of those rare occasions when the pieces of the jigsaw slot into place and you see with clarity the picture of the life you’ve been trying to create for the past weeks, months, years. And the next moment you’re slumped on the floor, with only the briefest awareness of how you got there and yet the sharpest recognition of the hot, tight pain invading your left arm and marching on towards your chest.

I remember thinking that no one survives pain like this.

After my heart had decided it was no longer for this world – long before the paramedics arrived, long before

that night even began it turns out: a heart that had been secretly destined to expire prematurely for as long as it had been beating – I found myself here.

I don’t actually know where here is. If I believed in heaven then I’d have been disappointed if this was it. There’s no one else around, no reunions with loved ones, no winged beings checking people in or out. I’m completely alone. And lonely. More lonely than I ever knew possible. There are no gardens, no rainbows, no magical worlds like those at the top of the Faraway Tree. Just whiteness spreading out into the infinite beyond, as far as the eye can see, in every conceivable direction.

The only respite in this interminable void is when occasionally, sporadically, the whiteness beneath me clears, like fog receding begrudgingly on the coldest of winter mornings, and I’m granted a dress-circle view of the living world to watch my family getting on with life without me.

Who grants it, or why, or how, I’ve no idea.

It’s both a blessing and a curse, being able to see and hear the people I’ve left behind, the people I love, but in silence, invisible, impotent. I’m lucky, I know, to be able to observe fragments of their lives, to listen to their conversations, to pretend – even if only fleetingly – that I’m a part of their lives still. But it’s painful, too, the inability to console them when they’re sad, to laugh with them when they’re happy or, simply, to hold and be held by them, to give and take refuge in the comfort of physical intimacy.

Perhaps it wouldn’t be quite as bewildering if it weren’t so unreliable, this incomprehensible access I have to the living; sometimes my time with them can last a whole day, at others just a matter of minutes. Sometimes I’m kept

waiting only a few hours between visits; at others long, solitary weeks go by without so much as a glimpse of the real world. I spend inordinate stretches of time alone in the impenetrable whiteness wondering what I might have missed in my enforced absence although, in truth, I have very little conception of the passage of days here.

And it’s frustratingly unpredictable too; sometimes I’m allowed to observe that which I most want to be a part of, while at others the air clears suddenly and I’ve no choice but to witness that which I’d most like to miss. It can be cruel like that.

I wonder, occasionally, when I let my fears and fantasies get the better of me, whether my presence here is a privilege or a punishment. Whether it’s a passing phenomenon or is set to continue for all eternity. Whether there may be a future in which I’ll be something other than a passive spectator of a life I no longer lead.

Sometimes I wonder whether any of what I’m seeing is actually real. In moments of desperation, I find myself questioning whether I am, in fact, dead at all. I begin to hope that I’m in a temporary coma and that the whiteness and the loneliness and the lives of the living I’m observing are nothing more than products of my unconscious fantasies.

I have a lot of time to think about these things.

I wonder, too, whether it’s more distressing to watch your family in mourning for you or whether it will be worse when, one day, they stop grieving and start living painlessly without you. I try to imagine how I’ll feel when I begin to occupy that place which all dead people must dread: that distant, rarely visited corner of someone’s mind, neatly packed away in a box marked ‘Memories’.

I often find myself thinking back to those conversations couples have about death, the conversations where each proclaims that should they die first they’d want their bereaved to carry on with life, meet someone new, be happy. I know now how delusional those conversations are. How untruthful. I know now that the only thing in the world worse than dying is the fear that one day you’ll be replaced and that life will continue with only the faintest echo of your existence.

Because to our loved ones, at least, we’re all irreplaceable, aren’t we?

SHOCK

Chapter 1

Today is my anniversary. Not my wedding anniversary or my engagement anniversary or the anniversary of the day Max and I first met at a friend’s wedding and knew immediately that this could be something special in a way that I’d always imagined only ever happened in movies.

Today is my Death Anniversary. A year ago today I was still alive, with fifteen hours remaining before the arrhythmia I’d been oblivious to for the past thirty-six years would fatally disturb the supply of blood to my left ventricle, which in turn would cease pumping blood to my brain which would, in a matter of minutes, kill me.

Anniversary probably isn’t the right word, is it?

I’ve wondered a lot over the past few days, ever since I heard Max and his parents discuss it, what Max and Ellie and my mum and all the other people whose lives I used to be a part of will do today. I’ve wondered whether it’s maudlin and self-indulgent and even selfish of me to hope that they’ll commemorate it somehow. But I also know that I’ll be devastated if they don’t.