The Design of Future Things (12 page)

Read The Design of Future Things Online

Authors: Don Norman

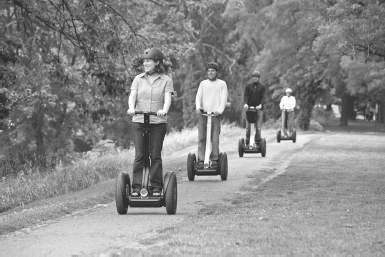

Contrast the natural interaction of horse and rider, person and Cobot, or person and the Segway Transporter with the more

rigid interaction between a person and the automatic flight control of an airplane or even the cruise control of an automobile. In the latter, the designers assume that you deliberately set the control, turn it on, and then have nothing more to doâuntil it fails, that is, when you are suddenly asked to recover from whatever problem has overwhelmed the automation.

F

IGURE

3.4

The Segway® Personal Transporter. A kind of collaborative robot, where control is done by leaning in one direction or another. Naturally, easily, both human and the transporter form a symbiotic unit.

(Photo used with permission of Segway Media.)

The examples of natural, responsive interaction discussed in this section illustrate a natural application of machine intelligence and collaborative power to provide a true machine+person symbiosisâhuman-machine interaction at its best.

Â

Servants of Our

Machines

CIRCLE 14 HOURS

April 1. Hampstead, MA. Motorist Peter Newone said he felt as if a nightmare had just ended. Newone, 53, was driving his newly purchased luxury car when he entered the traffic circle in the city center around 9 a.m. yesterday, Friday. The car was equipped with the latest safety features, including a new feature called Lane Keeping. “It just wouldn't let me get out of the circle,” said Newone. “I was in the inner-most lane, and every time I tried to get out, the steering wheel refused to budge and a voice kept saying over and over, âwarning, right lane is occupied.' I was there until 11 at night, when it finally let me out,” Newone said from his hospital bed, his voice still shaky. “I managed to get out of the circle and to the side of the road, and then I don't remember what happened.”

Police say they found Newone collapsed in his car, incoherent. He was taken to the Memorial Hospital for observation and diagnosed with extreme shock and dehydration. He was released early this morning.

A representative of the automobile company said that they could not explain this behavior. “Our cars are very carefully tested,” said Mr. Namron, “and this feature has been most thoroughly vetted by our technicians. It is an essential safety feature and it is designed so that it never exerts more than 80% of the torque required, so the driver can always overrule the system. We designed it that way as a safety precaution. We grieve for Mr. Newone, but we are asking our physicians to do their own evaluation of his condition.”

Police say they have never heard of a similar situation. Mr. Newone evidently encountered a rare occurrence of continual traffic at that location: there was a special ceremony in the local school system which kept traffic high all day, and then there was an unusual combination of sports events, a football game, and then a late concert, so traffic was unusually heavy all day and evening. Attempts to get statements from relevant government officials were unsuccessful. The National Transportation Safety Board, which is supposed to investigate all unusual automobile incidents, says that this is not officially an accident, so it does not fit into their domain. Federal and state transportation officials were not available for comment.

Cautious cars, cantankerous kitchens, demanding devices. Cautious cars? We already have them, cautious and sometimes

frightened. Cantankerous kitchens? Not yet, but they are coming. Demanding devices? Oh, yes, our products are getting smarter, more intelligent, and more demanding, or, if you like, bossy. This trend brings with it many special problems and unexplored areas of applied psychology. In particular, our devices are now part of a human-machine social ecosystem, and therefore they need social graces, superior communicative skills, and even emotionsâmachine emotions, to be sure, but emotions nonetheless.

If you think that the technologies in your home are too complex, too difficult to use, just wait until you see what the next generation brings: bossy, demanding technologies, technologies that not only take control of your life but blame you for their shortcomings. It is tempting to fill this book with horror stories, real ones that are happening today plus imagined ones that could conceivably come about if current trends continue, such as the imaginary story of Mr. Newone.

Consider poor Mr. Newone, stuck in the traffic circle for fourteen hours. Could this really happen? The only real clue that the story isn't true is the date, April 1, because I wrote this story specifically for the yearly April Fool's edition of the RISKS digest, an electronic newsletter devoted to the study of accidents and errors in the world of high technology. The technologies described in the article are real, already available on commercially sold automobiles. In theory, just as the spokesperson in the story says, they only provide 80 percent of the torque required to stay in the lane, so Mr. Newone presumably could have overcome that force easily. Suppose he were unusually timid, however, and as soon as he felt the resisting force on the

steering wheel, he would immediately give in. Or what if there were some error in the mechanics, electronics, or programming of the system, causing 100 percent of the force to be deployed, not 80 percent. Could that happen? Who knows, but the fact that it is so plausible is worrisome.

But lo! men have become the tools of their tools.

âHenry Thoreau,

Walden

Â

When Henry Thoreau wrote that “men have become the tools of their tools,” he was referring to the relatively simple tools of the 1850s, such as the axe, farming implements, and carpentry. Even in his time, however, tools defined people's lives. “I see young men, my townsmen, whose misfortune it is to have inherited farms, houses, barns, cattle, and farming tools; for these are more easily acquired than got rid of.” Today, we complain about the maintenance all our technology requires, for it seems never ending. Thoreau would have sympathized, for even in 1854 he compared the daily toil of his neighbors unfavorably to the twelve labors of Hercules: “The twelve labors of Hercules were trifling in comparison with those which my neighbors have undertaken; for they were only twelve, and had an end.”

Today, I would rephrase Thoreau's lament as “People have become slaves to their technology, servants of their tools.” The sentiment is the same. And not only must we serve our tools, faithfully using them throughout the day, maintaining them,

polishing them, comforting them, but we also blithely follow their prescriptions, even when they lead us to disaster.

It's too late to go back: we can no longer live without the tools of technology. Technology is often blamed as the culprit: “technology is confusing and frustrating,” goes the standard cry. Yet, the complaint is misguided: most of our technology works well, including the tool Thoreau was using to write his complaint. For that matter, Thoreau himself was a technologist, a maker of tools, for he helped improve the technology in the manufacture of pencils for his family's pencil business. Yes, a pencil is a technology.

Tech·nol·o·gy (

noun

): New stuff that doesn't work very well or that works in mysterious, unknown ways.

In the common vernacular, the word “technology” is mostly applied to the new things in our life, especially those that are exotic or weird, mysterious or intimidating. Being impressive helps. A rocket ship, surgical robots, the internetâthat's technology. But a paper and pencil? Clothes? Cooking utensils? Contrary to the folk definition, the term

technology

really refers to any systematic application of knowledge to fashion the artifacts, materials, and procedures of our lives. It applies to any artificial tool or method. So, our clothing is the result of technology, as is our written language, much of our culture; even music and art can be thought of as either technologies or products that could not exist without the technologies of musical instruments, drawing surfaces, paints, brushes, pencils, and other tools of the artists and musicians.

Until recently, technology has been pretty much under control. Even as technology gained more intelligence, it was still an intelligence that could be understood. After all, people devised it, and people exerted control: starting, stopping, aiming, and directing.

No longer. Automation has taken over many tasks, some thanklessâconsider the automated equipment that keeps our sewers running properlyâand some not so thanklessâthink of the automated teller machines that put many bank clerks out of work. These automated activities raise major issues for society. Important though this might be, however, my focus here is on those situations where the automation doesn't quite take over, where people are left to pick up the pieces when the automation fails. This is where major stresses occur and where the major dangers, accidents, and deaths result.

Consider the automobile, which, as the

New York Times

notes, “has become a computer on wheels.” What is all that computer power being used for? Everything. Controlling the heating and air conditioning with separate controls for the driver and each passenger. Controlling the entertainment system, with a separate audio and video channel for each passenger, including high-definition display screens and surround sound. Communication systems for telephone, text messaging, e-mail. Navigation systems that tell you where you are, where you are going, what the traffic conditions are, where the closest restaurants, gas stations, hotels, and entertainment spots are located, and paying for road tolls, drive-through restaurants, and downloaded movies and music.

Much of the automation, of course, is used to control the car. Some things are completely automated, so the driver and

passengers are completely unaware of them: the timing of critical events such as spark, valve opening and closing, fuel injection, engine cooling, power-assisted brakes and steering. Some of the automation, including braking and stability systems, is partially controllable and noticeable. Some of the technology interacts with the driver: navigational systems, cruise control, lane-keeping systems, even automatic parking. And this barely scratches the surface of what exists today, and what is planned for the future.

Precrash warning systems now use their forward-looking radar to predict when the automobile is apt to get into a crash, preparing themselves for the eventuality. Seats straighten up, seat belts tighten, and the brakes get ready. Some cars have television cameras that monitor the driver, and if the driver does not appear to be looking straight ahead, they warn the driver with lights and buzzers. If the driver still fails to respond, they apply the brakes automatically. Someday, we might imagine the following interchange at a court trial:

Prosecutor:

“I now call the next witness. Mr. Automobile, is it your sworn testimony that just before the crash the defendant was not watching the road?”

Automobile:

“Correct. He was looking to his right the whole time, even after I signaled and warned him of the danger.”

Prosecutor:

“And what did the defendant try to do to you?”

Automobile:

“He tried to erase my memory, but I have an encrypted, tamper-proof storage system.”

Your car will soon chat with neighboring cars, exchanging all sorts of interesting information. Cars will communicate with one another through wireless networks, technically called “ad hoc” networks because they form as needed, letting them warn one another about what's down the road. Just as automobiles and trucks from the oncoming lane sometimes warn you of police vehicles by flashing their lights (or sending messages over their two-way radios and cell phones), future automobiles will tell oncoming autos about traffic and highway conditions, obstacles, collisions, bad weather, and all sorts of other things, some useful, some not, while simultaneously learning about what they can expect to encounter. Cars may even exchange more than that, including information the inhabitants might consider personal and private.