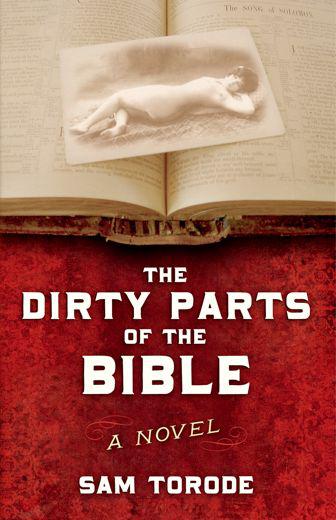

The Dirty Parts of the Bible: A Novel

Read The Dirty Parts of the Bible: A Novel Online

Authors: Sam Torode

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #Action & Adventure, #General, #Literary, #Fiction & Literature

THE DIRTY PARTS

OF THE BIBLE

A Novel by Sam Torode

Copyright © 2011 by Sam Torode

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Craw’s poems are adapted from the works of Henry Longfellow. The hobo songs are adapted from

Beggars of Life: A Hobo Autobiography

by Jim Tully. All song lyrics quoted are in the public domain.

eBook design and formatting by Jenna Lundeen of

Lundeen Literary

.

This book is available in

paperback from Amazon.com

.

eBook License Notes:

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each person you share it with. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then you should return to the seller and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the author’s work.

I

N

the beginning, Mama cursed.

The only time my mother ever swore—or so I was told—was the day I was born. According to Granny, Mama would have made a sailor blush. I weighed nine pounds and had the biggest head of any baby the midwife had ever delivered. “God damn it all to hell!” she yelled, grabbing Father by the collar. “You will never touch me again, you son of a bitch!”

Which explains why I don’t have any siblings—and a whole lot else besides.

I was named Tobias after my great grandfather, the original Tobias Henry, who left Kentucky and settled in Texas sometime in the mid-1800s. That’s where I was born, though I have no memories of my first years in Texas; my father moved us to Michigan when I was three. But somehow, someday, I was destined to return. Maybe it was the spirit of old Tobias in my blood.

Or maybe I felt drawn back to Texas because I hated Michigan winters. We lived north of Grand Rapids, in a little town called Remus, where my father was the Baptist pastor. I had good reasons for hating winter—for one thing, I’d have to trudge to the outhouse through four feet of snow. And, once I got to the outhouse, I couldn’t sit down or my ass would freeze to the seat.

But Father loved winter. Not Christmastime, mind you, but the dead of winter—that bleak stretch between January and March when old folks lose the will to live. Being a pastor, it was booming business for my father; but it wasn’t just the funerals that made him love winter. What he relished was the chance to discipline the flesh, to bring the passions under the Spirit’s control. “Warm weather pampers a body,” he’d say. “But winter mortifies the flesh and invigorates the soul. There’s nothing like a brisk, biting wind to fend off gluttony and lust.”

I could see his point: it’s hard to fornicate when your balls are frostbitten.

+ + +

Easter Sunday, 1936, was one of those sumptuous spring mornings Father warned against. Before my parents were out of bed, I headed out to Leach Lake. I was raised never to fish on Sunday and I knew I was heaping God’s wrath upon my head, but I had my reasons.

The air at the lake was sweet with the scent of grass and mud. Dragonflies were swooping in locked pairs. Sunfish were cavorting on their sandy beds. Frogs were humping in the muck. Crawdads were doing whatever it is crawdads do. All of nature seemed caught up in a carnival of love—except for me. I sat on a carpet of matted, yellow weeds, snapping twigs between my fingers and longing for Emily Apple.

Emily. I’d loved that girl since the third grade, when she was gangly, buck-toothed, and freckle-faced. What was it about her that pierced my heart? It wasn’t sexual. Heck, our chests were the same size.

That changed in seventh grade. As the girls in our class started looking more womanly, Emily exceeded them all. She’d stand at the blackboard multiplying and dividing numbers, while my mouth gaped open—enthralled by the way her cotton dress clung to her budding breasts. And just to think: I was the boy who’d discovered her first.

But, within a year or two, it became apparent that all my affections meant nothing. Emily’s new-sprung charms attracted older boys like bees to honey. Boys who had jobs. And money. And drove cars. I didn’t have a chance.

I kept hope alive all through high school, while Emily dated Lars Lundgren, a big Nordic bastard with more hair under one armpit than I had on my whole body. Lars was two years older than me. By the spring of ’36, he was an all-American in football and track at Northern Michigan. In April, Emily accepted his proposal.

Lars was coming home for Easter, and he and Emily were set to announce their engagement that morning. Which is why I was skipping church to go fishing. Easter or not, damned if I was going to sit in the pew behind them while Lars draped his sweaty arm around her shoulder.

Every night for I don’t know how many years, I’d prayed that God would make Emily mine. He hadn’t kept up his end of the bargain, I figured—why should I keep up mine? Then and there, on the banks of Leach Lake, I vowed never again to waste another breath in prayer.

+ + +

While I was busy apostatizing, my father was preaching his Easter sermon. I didn’t need to be in church to know what he was preaching about; it was the same thing every Sunday.

“You may call yourself a Christian,” he’d say, “but if you keep a bottle of liquor or a deck a cards in your cupboard, you might as well be a pagan. And don’t try to tell me you keep that whiskey for medicinal purposes only. Would you have the devil for your doctor?”

My father, the Reverend Malachi Henry, was a fierce opponent of liquor, dancing, gambling, whoring, and all other forms of worldly enjoyment. He reminded me of a military general as he paced back and forth behind the pulpit, firing off Bible verses like bullets.

After hitting the easy targets—gambling and drinking—he’d set his sights on more subtle evils, like dancing. “Why, it’s nothing more than rutting set to music. I can’t describe to you what passes under the name of dancing today. You might say, ‘But preacher, here in Remus we only have square dances.’ Well, a square dance might start innocent, but it sure don’t take long to cut off the corners.”

Father hadn’t always been so grim. He taught me to fish when I was a boy, and my happiest memories of childhood are of the two of us at the lake. But his “moods,” as Mama called them, had grown worse over the past few years. To get out from under his dark cloud, I started going fishing alone.

Whenever I needed to clear my head, I lit out for the lake. I never liked exploring the woods like other boys. To me, a forest is just a bunch of trees, but lakes and rivers are alive. Water is to the land what blood is to the body.

I never learned to hunt because Father thought it was unseemly for a preacher to carry a gun. By Remus standards, I might as well have been born without a penis. (The fact that Remus rhymes with penis was an endless source of amusement for my friends and me. It was our

only

source of amusement.)

Remus was a timber town in its heyday, but the timber ran out in the ’20s. Most of the loggers moved to Detroit to work in the auto factories. Those who hung on lived in shanties or shacks of their own making. For these men, there wasn’t anything else to do besides hunt. Walking across town any given day, I’d see five or ten deer strung up from trees, their innards all hanging out. If not for the deer, the men would have shot each other for sport.

Michigan is a long way from Glen Rose, Texas, where my parents grew up. Why did Father move us? He claimed that the Spirit had called him. I figured he’d dragged Mama and me north to torture us.

Maybe Remus was the only town that would take him. Down south, most places had a surplus of Baptist pastors already. Texas’s main exports are cotton, oil, and preachers.

Why did Father leave the family farm and get into the preaching racket? Here’s how he tells it: One morning when he was milking, a cow kicked him upside the head. As he lay on his back staring up at the sky, the clouds parted and Jesus himself appeared.

Jesus:

Malachi!

Malachi: Yes, Lord?

Jesus:

I want you to preach.

Malachi: But I don’t know how.

Jesus:

Go to the seminary.

Malachi: The cemetery?

Jesus: No—the

seminary

. Fort Worth Baptist Seminary.

You’d think that my father would have packed his bags for seminary that very afternoon. But no—he fought it. He was in a musical group with his brothers at the time, and didn’t want to leave home. More importantly, he was keen on a certain girl in town. Jesus would just have to wait.

My mother, Ada Jackson, was quite a looker in her day. (She still is, in a motherly sort of way.) She was elected Cotton Queen at the county fair, and my father first noticed her there in the parade. He wooed her with his guitar, crooning songs like “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.”

When Mama first told me that story, I couldn’t believe it. I never knew my father to play a guitar, much less sing anything other than hymns. What made him change? I didn’t know—not till after Father’s accident.

+ + +

That Easter Sunday, I didn’t catch a single fish. I’d never been skunked on a warm April day before—surely God was smiting me.

I waited till dusk before heading home, and made sure the lamp was burning in Father’s study window before I crept inside and up the stairs to my room. I slipped under the covers without taking off my fishing clothes.

From the kitchen below, I could hear the tinkling of dishes as Mama washed them. The door to Father’s study creaked open and slammed shut, and heavy footsteps made their way across the hall.

My parents always had their serious talks in the kitchen; they never suspected that I could hear every word. This night, there was no talking for a long while. Father huffed and groaned; Mama kept scrubbing. Finally, Father spoke. “Ada, what have we done to deserve this?”

Mama didn’t answer. Father repeated his question, louder and more forcefully. “Where did we go wrong?”

Still no answer. But I could almost hear the sound of gears clanking in Father’s head as he marshaled his arguments, preparing to strike.

“Ours is a Christian family,” he began, his voice booming as though he were in church. “We do things different from the rest of the world. And one of the ways we honor God is by keeping the Sabbath. That’s not just a suggestion—no, sir. It’s one of God’s great commandments.”

When Father paused to reload, Mama sighed. “Tobias is almost twenty years old,” she said. “It’s time for him to make his own decisions.”

“As long as the boy is under my roof he is under my discipline,” Father shot back. “A child is like an unruly tree—in order to grow up straight, he must be pruned. ‘Raise up a child in the way he should go, and he will not depart from it.’”

I knew I was in trouble whenever he started quoting Scripture.

“He’s not a child,” Mama said.

“Dishonoring the Sabbath is grave enough,” Father continued. “But that’s not my only concern. The boy has grown despondent—dull to the things of the Lord. He doesn’t study the Scriptures. Why, the only thing he reads on Sunday is the funny papers. He fritters away his time on—”