The Discovery of Heaven (77 page)

Read The Discovery of Heaven Online

Authors: Harry Mulisch

Suddenly, in an even more distant past, he saw his mother's bedroom: the open drawers and cupboards, her clothes in a pile on the ground. That would never stop. As Onno was wont to say: "family is forever." Tsjal-lingtsje knew nothing about any of those things; perhaps he should tell her something about the grandmother and grandfather of the child that she wanted to have by him. What was it to be called? Octave? Octavia? After Onno's one-to-two ratio of the simplest perfect consonant interval? It seemed that nowadays you could determine sex during pregnancy by using an ultrasonic echo—in fact as new a principle as Quinten needed for his "historioscope." He looked at the house through the open door. The television was off; there was a light on upstairs in the bedroom. She was reading in bed,

The Brothers Kammazov,

which he had prescribed for her, and was waiting for him to come up.

Gradually, his head sank back and his eyes closed for a moment. He came to himself with a start and sighed deeply a couple of times. The smell of tarred wood. He poured himself another glass and sank back again; with his head against the chair he stared through the shed. It was though he could feel his life like a large object that he could put his arms around, like a dog that was much too large on his lap. Everything kept increasing, becoming more and more complicated, just as an acorn gave birth to an ethereal, symmetrical plant, which grew into a gnarled, twisted oak that retained nothing of its almost mathematical origin. And yet it had once had that form. How could one have been transformed into the other? And if that couldn't be explained, how could that transition have taken place? The problems, he considered, consisted not in what happened, because that was simply what happened, but in how what happened was conceivable. The universe had emerged from a homogenous origin—then how, in that case, could it look as it looked now, with a division of the solar systems as it was and no other way? Why hadn't anything remained homogenous? Why was the earth different from the sun? And the sun different from a quasar? How was it possible for a chair to be here and a rake there? How could he himself exist and be different from Onno? How could he now be thinking something different than he had just been thinking, and shortly something different from now? What had happened meanwhile? Or had the origin perhaps not been homogenous? Of course he knew the theories, on initial quantum fluctuations, but did they really explain the difference between him and Onno?

He looked at the planks of the shed. They resembled each other, but that's how they'd been made. Moreover, they weren't exactly the same; one of them was a little wider than the others, a little darker, a little lighter, and something appeared to be carved in one plank. He screwed up his eyes, but he couldn't see what it was. Because he felt he should know, he got out of his chair with a groan and went across to it. There were letters and figures, thin and almost illegible; he leaned against the plank with one hand and put the other over one eye.

Gideon Levi. 8.3.1943.

He put the other hand against the plank and dropped his head, exhausted. The shed came from Westerbork. Forty-two years ago a boy had carved that there with his pocketknife. After he had succumbed to the gas, someone had bought the hut and put it here in his garden. Through the small window, which he now also understood, he looked at the house. He wanted to tell Tsjallingtsje what had happened and that the shed must be demolished the very next day; but the light in the bedroom had gone out. Pale moonlight illuminated the front of the house. He looked around. The space was too small to have served as a barracks; perhaps it had been a school, or the sewing room. Perhaps his mother had been put to work here. Supporting himself on the planks, he found his way back to the chair, which he sank into with a flourish, and upturned the bottle over his glass.

After that he must have dropped off to sleep for a moment. He woke because it had become cold and damp in the shed; but he still did not stand up to shut the door. It was past twelve. He knew he was drunk and that he ought to go to bed, but he had the feeling that either beneath or beyond his drunkenness his brain was still working—perhaps less inhibitedly than when he was sober. With his eyes closed, rocking back and forth a little in his chair, he thought back to the computer printouts of that afternoon. Was the result really so absurd? He saw the sheets very clearly in front of him, as though he were really looking at them. And suddenly it was as though a great light were turned on in him: he understood everything!

In a split second everything had come together—but what was it? He knew the answer, but it seemed as difficult to unravel as the question. The so-called infinite velocity of MQ 3412 was not an error, as his colleagues all over the world thought, but revealed a constellation that had not occurred to anyone! It was like the discovery of penicillin by Fleming: his assistant had put away a petri dish with a staphylococcus culture in it to throw it in the wastebin, because it had gotten mold on it; but Fleming himself had another look and saw that it wasn't the bacteria that had attacked the penicillin, but the penicillin that had attacked the bacteria—which subsequently saved the lives of millions of people and won him the Nobel Prize. The Nobel Prize! There was no Nobel Prize for astronomy, but there was for physics. His thoughts wandered to Stockholm, where he would be standing on the platform in a tailcoat, on that circle with the inscribed

N,

in his hands the gold medal, received from the hands of the king—or at least he could expect an honorary doctorate too, in Uppsala ...

He put aside these fantasies and forced himself as far as he could to think through his discovery. The supposed infinite velocity pointed to a distortion of perspective! It was like with the vanishing point: at the horizon the rails met, so that no train could get through, because it would be destroyed at that point—and on the other side of it there was nothing else. And yet trains passed through it, both from one side and from the other. Quasar MQ 3412 wasn't a quasar at all! Or perhaps it was a quasar but everyone regarded it as something that it wasn't, since another object in a geodetically straight line was behind it, still farther away, which was covered by it. Perhaps that was not a black hole but the primeval singularity itself: the point in the firmament where the Big Bang could still be seen!

Perhaps last night the VLBI had received signals from the other side right through that vanishing point, which had tunneled right through from that vanishing point—or rather: through the vanishing point! Black holes too, from which theoretically no information could emerge, turned out on closer inspection to leak like sieves. In a negative space-time suddenly all those infinities had become visible, those which theoreticians invariably encountered in their mathematical descriptions. Shorter than 10

-13

th second from the zero moment, Planck time, the hypermicroscopic universe was a theoretical madhouse; for the zero-moment calculations arrived at a paradoxical universe with a circumference of zero, hence a mathematical point, and at the same time with infinite density, infinite curvature of space-time, and infinitely high temperature. There, both the general theory of relativity and the quantum theory collapsed.

Everyone agreed that a new, overarching theory was necessary to be able to continue the discussion; the occurrence of infinities was always regarded as a sign that something was fundamentally wrong with the theory—but they really existed then; they'd been observed twenty-four hours ago! It was just that no one thought of interpreting it like that: the whole of cosmology was the victim of an optical illusion! And wouldn't it in fact be idiotic if the beginning of the universe were

not

linked with infinities. If something emerged from nothing, then that was of course an infinitely different matter than when something emerged from something else—the incomprehensibility was precisely the

esssence

of the fact that the world was there and not not there! He sat up. Now he must go to sleep and tomorrow immediately work this out and publish it as soon as possible, before someone else hit on the idea.

Instead of getting up, he held the bottle over his glass once more. When nothing more came out of it and he was about to put it down, it fell from his grasp. He put out an arm to pick it up but got no farther. As he let his arm hang down, his chin dropped onto his chest. Suddenly it occurred to him that in the last few months a similar new theory was causing excitement in physics, since it could perhaps finally reconcile quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity: the great unification— the long-sought-after Theory of Everything! This summer a large conference was going to be devoted to it in Bari—shouldn't he go? Up to now elementary particles, like electrons, had always been regarded as pointlike, zero-dimensional, which of course also meant that their energy in that point was infinitely great, and hence also their mass; strangely enough no one had ever worried about those infinities, but by now he was no longer surprised about that bungling and selective indignation: it was no different in science than in politics. The new theory suggested that elementary particles were not zero-dimensional but uni-dimensional: super-small strings in a ten-dimensional world. Not only all particles, also the four fundamental forces of nature and the seventeen natural constants, could be explained by the vibration of otherwise completely identical strings. Strings! The monochord! Pythagoras! Had science arrived back where it had begun? Was music the essence of the world?

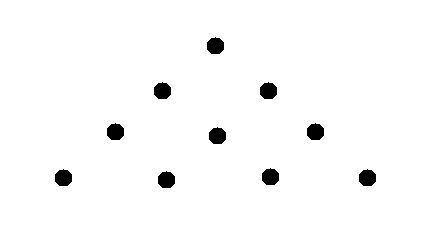

The image of Ada appeared before his eyes, the cello between her parted legs. "All things are numbers," Pythagoras had said. For him ten was the sacred number, which you could count on your fingers, like the Ten Commandments and the ten dimensions in the superstring theory. Ten was the "mother of the universe," and from long-forgotten boyhood reading he suddenly remembered Pythagoras's mystical tetractys, the four-foldness, the symbolic depiction of the formula "one, two, three, four," with which his pupils swore the oath:

As a true Greek, thought Max, Pythagoras of course rejected complete infinities, although in his famous thesis he had encountered irrational numbers—but Max himself needed them in order to interpret the observations of the VLBI, that is, the origin of the world: the Big Bang as infinite music! Suddenly he lifted up his head and opened his eyes. Because the light dazzled him, he got up unsteadily, turned off the lamp, and sank back into the chair.

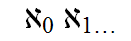

Was it possible that the mathematics already existed for this? When Einstein needed a non-Euclidian, four-dimensional geometry for his curved space-time, it turned out to have been created decades before by Gauss and Riemann. If the world was first and last a realized infinity, then he himself might be able to turn to Cantor, the founder of set theory. Cantor! The singer! As a student he had occupied himself for a while with Cantor's shocking theory of transfinite cardinal numbers, the infinite number of complete infinite numbers, but that had been a long time ago. He remembered the vertigo that had overcome him on his visit to the Orphic Schola Cantorum: its alephs,

his Absolutely Infinite

.

.