The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini and other Strange Stories (31 page)

Read The Dreams of Cardinal Vittorini and other Strange Stories Online

Authors: Reggie Oliver

‘So I did go back the following Saturday,’ said Berrigan, ‘for the last time, as it turned out. This is what happened.

‘I heard the nuns’ confessions, as usual, and when this was over I felt the need to spend a little time praying in the chapel alone. I knelt down in one of the choir stalls and tried to take my mind down into myself, into the inner well of quiet, as I call it. I knew from the first that something was disturbing my efforts. I thought that it was my own wayward mind; I tried to untense myself, but slowly it was borne in on me that the unease came from an external source. A damp, rotten smell was beginning to pervade my senses, like old cabbages decaying in a wet cellar. The air became clammy. I looked up from my praying hands to see something black and slightly shiny dip behind the choir stall opposite me. It was humped and shaped like a human back, but who would be crouching in one of the chapel choir stalls? And why?

‘I really can’t describe to you my feelings. The memory of them has been blotted out, so that only the bare physical—if they were physical—facts remain. I remember the objective part of me thinking that it was like a waking dream because I found that I could neither move nor speak. I heard a sort of confused bumping coming from behind the choir stalls as if something was blundering about blindly, and there were long, gasping inhalations and exhalations of breath. Then it began to emerge from behind the choir stalls and crawled out into the aisle. It was without head or limbs but the size of a human being, a great lump made of black cloth like a nun’s habit and wet, dreadfully wet. It oozed water as it inched its way towards me across the chapel floor, headless and black, but not without a purpose.’

Berrigan said nothing for a few moments, but just panted heavily for a while, as if he had been running hard and was out of breath.

‘That was not the worst of it. That was only the physical manifestation, but I was aware that in it a force was concentrating, vibrating and growing. I would say it was like a pulse. It was an essence of some life form, deeply ancient and primitive. . . . But not primitive in the way that we normally mean, not in the sense of crude, or stupid. No. This was a higher form than us, essential, spiritual, above all, pure. It had a profound intelligence too, one that somehow knew what I was thinking almost before I did myself. But I haven’t mentioned the essential fact. It was evil: pure, unadulterated malevolence, nothing added, nothing removed. It was the thing that had operated through that nun. I knew that. How, I can’t tell you. Call it a guess. Call it intuition.

‘Before that moment I had not understood the concept. I had known sin in many of its forms, some of them pretty awful. I had even met a murderer or two. But in that chapel I was confronting evil itself which, in all senses of the word, was unspeakable.’

After a long silence he suddenly laughed.

‘You know the irony of it all? The next thing I remember I was in St Francis Xavier’s. They told me I had had a nervous breakdown or some such.

‘Slowly I began to piece together what had happened, but I doubt if I would be here today if it hadn’t been for a very brave young woman. You remember I told you about Sister Joseph, the little nun with buck teeth who first mentioned the name of Sister Assumpta? Well, she defied her vow of obedience to come and see me. She said she felt responsible and guilty about not telling me more at the time. Bless her, wherever she is. Apparently I had been found lying in the aisle of the chapel in a pool of foul water. I was incoherent, sometimes violent. Only towards myself though, thank the Lord.’

‘So, did Sister Joseph tell you more about Sister Assumpta?’ I asked.

‘She did. Not much, but perhaps enough. You see, Sister Assumpta had been a medical missionary in Western Samoa, highly respected, but when she came back everyone agreed she had changed in some way, not for the better. She was shunted from convent to convent, each time her presence causing trouble of some kind. People were vague: no definite accusation could be laid at her door, she was just trouble. Eventually she ended up at the House of the Sacred Heart, Crampton “on retreat”. She was there for six months altogether. When I asked her about Sister Assumpta, Sister Joseph said her memories were oddly vague, but she knew she had felt from the first that her presence was in some way disquieting and unwelcome. She believed Sister Assumpta’s troublesomeness was connected with her time in Western Samoa. She could not be more specific.’

‘And Father Coughlin?’

‘Sister Joseph said she couldn’t believe that there was anything going on between Father Coughlin and Sister Assumpta, because it was clear he couldn’t stand her. Everyone remarked on it. But in the weeks before her death they had been seen together once or twice in odd places, and on the afternoon of Sister Assumpta’s death Sister Joseph saw Coughlin walking quickly along the banks of the River Durden in which she was later found dead.’

‘Did she tell the police?’

‘No. No. What would have been the point?’

I let that pass. ‘So, is the House of the Sacred Heart still there?’ I asked.

‘The community was disbanded soon after my little fiasco. No reason given.’

‘How very discreet.’

Berrigan gave a half smile and bowed his head in acknowledgement of my implied criticism. ‘When I was better I did some research and discovered that the Samoan tribes among which Sister Assumpta had worked had some strange and rather nasty customs. It gave me an unpleasant shock to read in some work of anthropology that they had a practise known as “Alona Shaga”—those two words which had occurred so frequently in Father Coughlin’s demented exercise book. The words roughly mean “catching the dead man’s breath”. Apparently, if you are able to catch the last breath of a dying man in your mouth, especially if that man was himself a shaman of some sort, you are imbued with all kinds of powers from the spirit world. According to the Samoans you can start hurricanes, strike down your enemies just by breathing on them, all sorts. Only inundation in water can dampen the force of this power, so to speak. Rubbish of course, but there it is.’ Berrigan spoke the last sentence with a forced casualness that carried no conviction. ‘So,’ he concluded briskly, ‘that’s my story.’

There was a pause. Berrigan looked at me with eyes that expressed a lifetime of exhaustion and pain. I was sure he needed to say something more even if he didn’t want to, so I did not move but waited for him to speak again.

‘Why it remains with me till today is that I found myself utterly powerless against it. Whatever it was. Oh, you might say, that is just a blow to your vanity. And perhaps it is. Perhaps. But I felt that I had been up against a force as absolute and inexorable as the love of God. And almost as powerful. . . . Sometimes —I can’t help feeling—more powerful. . . . Not that I believe that, mind! But I felt. And I still feel. I suppose that makes me a sort of Manichee.’

‘Feeling is not believing,’ I said.

‘I hope not,’ said Father Berrigan.

Three weeks later a massive stroke ended his life.

THE COPPER WIG

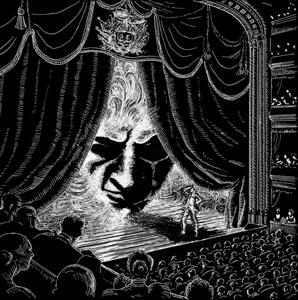

You almost certainly will not have heard of, let alone read, Mr F. Harrison Budd’s

Random Reminiscences

of a Strolling Player

(privately printed, 1925): it is not a distinguished example of the genre. The observation is commonplace, the humour ponderous and the endless litany of parts played and press eulogies received tedious beyond belief. But, like nearly all the autobiographies I have come across, it contains one story worth preserving, and, as Mr Budd’s literary executor, I consider it my duty to give this a wider audience. Though I have cut out the occasional irrelevant digression I have not rewritten anything. Budd’s style is rather quaint perhaps but it gives us a flavour of the times he lived in and the circles in which he moved.

**

It was in the early Summer of 1893 that I was summoned to join Mr Alfred Manville’s theatrical company at the town of Yarborough in the North of England. I would have preferred to wait for a London engagement—indeed Tree had promised me something in his next season—but my finances were perilously low, my landlady and tailor exigent, and my impatient youth could stand inactivity no longer. Besides, Manville had a fair reputation. He had once been known as ‘the Macready of the North’, but he was now content to manage the company, play the character roles and leave the leading parts to younger men.

Our tour of the Northern Circuit was to open with

One of the Best

and

Harbour Lights,

dramas made popular at the Adelphi Theatre by the ill-fated Mr William Terriss. I was engaged for a number of minor but not wholly negligible roles. The company was a comparatively small one, no more than a dozen or so players, but Manville, known by us all as ‘the Guv’nor’, produced on a lavish scale by the simple expedient of employing ‘supers’ in every town we visited to play very small parts and to populate the crowd scenes. These men and women, mostly enthusiastic amateurs, and often supplying their own costumes, would appear on stage for a pint of porter and the privilege of saying that they had once appeared in Mr Manville’s company.

Perhaps for safety’s sake, perhaps on the principle of ‘divide and rule’, the Guv’nor had engaged two leading men, Mr Edwin Marden and Mr Charles Warrington Fisher. They made an interesting and instructive contrast in character and talents. If Fisher was the subtler performer, Marden was the more dashing and undoubtedly the favourite with the public, largely perhaps because of his looks. For, though Fisher was by no means bad looking, Marden was half a head taller than him, wiry and muscular in build, and strikingly handsome. What perhaps distinguished them most, and advantaged Marden, was in the matter of hair. Fisher’s hair was pale, fine and, to tell an unvarnished truth, receding, but Marden had a magnificent head of wavy, copper-coloured locks. Fisher often resorted to a wig, and while wigs are all very well, they can never compete with the genuine article. Audiences in those days could be very cruel on actors they detected wearing them. ‘Remove your headpiece, sir, in front of a lady!’ some wit from the gallery would cry in the midst of a tender scene.

Contrary to what one might expect, Marden and Fisher were not rivals in the normal sense of the word. They did not quarrel or divide the company into warring factions and they rarely spoke of one another except to pay compliments. Superficially they appeared to be on the best of terms, even to the extent of occasionally sharing lodgings, but under the surface they were very different beings. Marden was breezy, outgoing and addicted to long walks when he had the leisure; Fisher was more thoughtful and inward looking. If he took a walk it was to investigate sixpenny bookstalls in the town, or study the architecture of the local church.

Our first weeks were harmonious and successful. Marden and Fisher had equal status and billing in our first two plays, but I was conscious of a certain atmosphere developing between them when Mr Manville decided to put into the repertoire that fine drama

The Honour of the Tremaines.

This ever popular play was to be his chief attraction, and he decided to cast Marden in the leading role with Fisher supporting him as the hero’s friend.

The play is in four acts but the great moment comes at the end of the third. In case anyone is unfamiliar with

The Honour of

the

Tremaines

I must, for purposes which will become evident, briefly summarise the plot. Apart from the first act, the scene is laid in India, where Roger Tremaine and his friend Hubert La Rose are officers in the Loamshire Regiment. Tremaine has come to India under a cloud, having in the first act taken the blame for an incident of cheating at the card table of which Roger Tremaine’s elder brother the Marquess of Tremaine was actually guilty. Tremaine takes the guilt upon himself in order to protect the honour of the Tremaines and save the title from disgrace. In India he becomes popular with the regiment and falls in love with Emily, the Colonel’s daughter. Unfortunately there is a rival for her heart in the shape of one Captain Frederick Vosper. Vosper, the villain of the piece, contrives that Tremaine should fall into the hands of Nazir Ali, a ferocious local bandit. So all is set for the great third act, the final scene of which is laid in the officer’s mess of the Loamshires at Bangrapore. After dinner the conversation turns to the incident which drove Tremaine from England at which point Captain Vosper says: ‘I say Tremaine is a blackguard!’ Incensed by this, Tremaine’s friend Hubert La Rose rises from the table and thunders: ‘To any man who says that Roger Tremaine is a blackguard I give the lie!’ Tremendous applause. But this fine moment is eclipsed by what follows, for through the double doors of the mess staggers a man in the tattered uniform of an officer of the Loamshires. It is Tremaine himself who has escaped from the clutches of Nazir Ali! ‘I give the lie myself!’ he cries and collapses onto the table. Tumultuous applause. Curtain. It was a moment, like ‘I am Hawkshaw the detective!’ in Tom Taylor’s

Ticket of Leave

Man,

which never failed.

When I say that it was Marden who took the role of Tremaine and Fisher who played his faithful friend Hubert La Rose, you can imagine what a gulf was fixed between them in the eyes of the public, despite their ostensibly equal standing in the company. For that part alone Marden became ‘the idol of the ladies and the envy of the men’.

It has to be said that Marden took full advantage of the benefits conferred by the role. His success with the ladies of each town he visited was remarkable, a success he took with an easy careless arrogance which was not altogether likeable. He began to put on airs.

In Doncaster there occurred an incident which significantly worsened relations between Fisher and Marden. They had taken lodgings together at a Mrs Pardoe’s. Mrs Pardoe had a daughter named Judith, a beautiful girl of nineteen, to whom Fisher was greatly attracted. Indeed, I believe that he had formed an attachment to her during a previous stay in the town and they had corresponded. However, the long and the short of it was that in the course of the week Marden managed to seduce the young lady and, worse still, boasted of the conquest to some of his cronies in the company. When they pointed out to him that his friend Fisher had an interest in that direction he winked. ‘Ah, you see,’ he said, pointing meaningfully to his magnificent locks, ‘I won that race by a head’. The remark was accounted a great witticism in the company and was oft repeated. Not surprisingly when Fisher came to hear of it he was enraged. He said little at the time, but when Marden approached him at the end of the week and suggested they share lodgings once again, Fisher turned on his heel and stalked away from him in silence.

Relations between the two appreciably worsened in the ensuing weeks so that they barely spoke a word except on stage. The frost was greatly exacerbated by the extraordinary success of

The Honour of the Tremaines

. The Guv’nor dropped the other plays in his repertoire, and Marden’s personal triumph was reflected in the billing. His name now appeared above the title and in letters twice as large as anyone else’s (except, of course, the Guv’nor’s).

However, by the time we reached Slowbridge, that drab and deleterious Midlands town, Fisher and Marden seemed to be on better terms. For the first time in many weeks they exchanged cordial greetings in the theatre. It appeared that Fisher had become reconciled to playing second fiddle, though, in the light of what happened next, I have my doubts.

On the Thursday evening of the Slowbridge week I was making up in a dressing room of the Regent Theatre with several of my fellow performers, when the call boy knocked to call the quarter, twenty minutes before curtain up. Unusually for him, having knocked he entered and announced to us that Mr Marden was not in his dressing room; indeed, had not come into the theatre at all. We said that he should tell Mr Manville, but the boy seemed fearful. No doubt he realised that he should have alerted the management when Marden had not arrived at the half. I agreed to go with the boy to beard the Guv’nor in his lair. When Manville heard the news he gave instructions that we should hold the curtain for no longer than five minutes in case Marden turned up, but that meanwhile Mr Fisher should prepare to take over the role of Tremaine, and I that of the hero’s friend, Hubert La Rose. Mr Willington, the junior character man, was deputised to double my part, the small but showy role of Lieutenant Beauhampton, with that of his own, the comic Indian servant Babu. So it was. Marden failed to appear and we all went on and were word perfect in our altered parts.

Marden had disappeared without a trace. His movements on that day, as far as could be ascertained by the police, were as follows. The morning had been spent at his lodgings in Wendell Street. At noon he had ventured out for a walk and met Mr Fisher outside the White Hart Hotel in the centre of town and there they had lunch together. Witnesses declared that the two men had appeared to be on the most convivial terms. At two o’clock they left the White Hart together and then, according to Fisher, had gone their separate ways: Marden to walk by the canal, Fisher to examine the famous misericords in the choir stalls of Slowbridge church. After that there had been only one doubtful sighting of Marden. He had been seen by an itinerant match-seller from the other side of the canal running along the towpath, apparently in a state of some agitation. When asked if anyone had been following Marden the witness replied that he could not be sure.

Naturally some suspicion fell on Fisher, but no evidence could be found to contradict his account of events. Moreover, there was no body and so no certainty that there had been any foul play. Marden’s disappearance cast a shadow over the company, but the great principle of ‘the show must go on’ prevailed. Only one member of the company was inconsolable and this was our leading lady Miss Rose Manville, the Guv’nor’s daughter, with whom, it would appear, Marden had ‘an understanding’.

Fisher took the role of Tremaine very well indeed and if he was not quite as dashing as Marden he was perhaps more soulful, especially in the scenes with Miss Manville. (Miss Manville, however, had a great aversion to Fisher though, trouper that she was, she never showed it on stage.) Fisher’s wig, it was true, was not wholly satisfactory and often provoked a few derisive titters on his first entrance, but even this problem was solved.

Three weeks after Marden’s disappearance we were playing at the Alhambra Theatre, Derby (now alas a cinematograph palace). On our first night there Fisher sent a note by the call boy summoning me to his dressing room. Fisher had befriended me and I had responded after a fashion. We had similar, bookish tastes, but there was always something remote about him that I could never get behind. Closeness was barred and companionship taken up and dropped very much at his whim.

That night, as I entered his dressing room, Fisher seemed to be in a state of high excitement. A square cardboard box with a printed label on the top was situated in the middle of his dressing table. His eyes glittered and he wore a gleeful smile which did not seem to me entirely pleasant.

‘What do you think this is?’ he asked, indicating the box. ‘It came by carrier today!’ Obviously baffled astonishment was called for and I duly obliged.

Like a conjurer performing an important trick, he removed the lid of the box with a flourish and from a nest of tissue paper drew forth a magnificent copper-coloured wig. Then, with another flourish, he placed the wig on his head. It was astonishing. Even without the gauze stuck down with spirit gum the hair looked as if it belonged to him. It was a triumph of the wigmaker’s art. I congratulated him and he beamed exultantly. Once again I was conscious of something not quite nice about all this elation. I searched for a reason for my unease, and then it suddenly occurred to me: the hair was identical in colour and consistency to poor Marden’s! For a moment my horror must have become apparent because he looked at me enquiringly.

‘Are you going to wear that tonight?’ I asked.

‘Yes. Of course. Why not?’

‘Well, if I were you,’ I said, ‘I’d show it to Miss Manville first, before you go on stage with her.’