The Dumbest Generation (7 page)

Read The Dumbest Generation Online

Authors: Mark Bauerlein

The momentum of the social scene crushes the budding literary scruples of teens. Anti-book feelings are emboldened, and heavy readers miss out on activities that unify their friends. Even the foremost youth reading phenomenon in recent years, the sole book event, qualifies more as a social happening than a reading trend. I mean, of course, Harry Potter. The publisher, Scholastic, claims that in the first 48 hours of its availability

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

sold 6.9 million copies, making it the fastest-selling book ever. In the first hour after its release at 12:01 A.M. on July 16, 2005, Barnes & Noble tendered 105 copies per second at its outlets. Kids lined up a thousand deep in wizard hats to buy it as Toys “R” Us in Times Square ran a countdown clock and the Boston Public Library ordered almost 300 copies to be placed on reserve. In Edinburgh, author J. K. Rowling prepared for a reading with 70 “cub reporters” from around the world who’d won contests sponsored by English-speaking newspapers.

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

sold 6.9 million copies, making it the fastest-selling book ever. In the first hour after its release at 12:01 A.M. on July 16, 2005, Barnes & Noble tendered 105 copies per second at its outlets. Kids lined up a thousand deep in wizard hats to buy it as Toys “R” Us in Times Square ran a countdown clock and the Boston Public Library ordered almost 300 copies to be placed on reserve. In Edinburgh, author J. K. Rowling prepared for a reading with 70 “cub reporters” from around the world who’d won contests sponsored by English-speaking newspapers.

It sounds like a blockbuster salute to reading, with a book, for once, garnering the same nationwide buzz that a

Star Wars

film did. But the hoopla itself suggests something else. Kids read Harry Potter not because they like reading, but because other kids read it. Yes, the plots move fast, the showdown scenes are dramatic, and a boarding school with adults in the background forms a compelling setting, but to reach the numbers that the series does requires that it accrue a special social meaning, that it become a youth identity good. Like

Pokémon

a few years ago, Harry Potter has grown into a collective marvel. We usually think of reading as a solitary activity, a child alone in an easy chair at home, but Harry Potter reveals another side of the experience, and another motivation to do it. Reading

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets,

and the rest is to bond with your peers. It opens you to a fun milieu of after-school games, Web sites, and clubs. Not to know the characters and actions is to fall out of your classmates’ conversation.

Star Wars

film did. But the hoopla itself suggests something else. Kids read Harry Potter not because they like reading, but because other kids read it. Yes, the plots move fast, the showdown scenes are dramatic, and a boarding school with adults in the background forms a compelling setting, but to reach the numbers that the series does requires that it accrue a special social meaning, that it become a youth identity good. Like

Pokémon

a few years ago, Harry Potter has grown into a collective marvel. We usually think of reading as a solitary activity, a child alone in an easy chair at home, but Harry Potter reveals another side of the experience, and another motivation to do it. Reading

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets,

and the rest is to bond with your peers. It opens you to a fun milieu of after-school games, Web sites, and clubs. Not to know the characters and actions is to fall out of your classmates’ conversation.

If only we could spread that enthusiasm to other books. Unfortunately, once most young readers finished

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire,

they didn’t read a book with the same zeal until the next Potter volume appeared three years later. No other books come close, and the consumer data prove it. Harry Potter has reached astronomical revenues, but take it out of the mix and juvenile book sales struggle. The Book Industry Study Group (BISG) monitors the book business, and its 2006 report explicitly tagged growth in the market to Potter publications. Here is what the researchers predicted:

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire,

they didn’t read a book with the same zeal until the next Potter volume appeared three years later. No other books come close, and the consumer data prove it. Harry Potter has reached astronomical revenues, but take it out of the mix and juvenile book sales struggle. The Book Industry Study Group (BISG) monitors the book business, and its 2006 report explicitly tagged growth in the market to Potter publications. Here is what the researchers predicted:

Since no new

Potter

hardcover book is scheduled for release in 2006, but the paperback

Potter

VI will appear, we are projecting a 2.3 percent increase in hardcover revenues and a 10 percent surge in paperback revenues. Because

Potter

VII is not likely to be published in 2007, the projected growth rate for that year is a lackluster 1.8 percent.

Potter

hardcover book is scheduled for release in 2006, but the paperback

Potter

VI will appear, we are projecting a 2.3 percent increase in hardcover revenues and a 10 percent surge in paperback revenues. Because

Potter

VII is not likely to be published in 2007, the projected growth rate for that year is a lackluster 1.8 percent.

In fact, another Potter book did come out in July 2007, one year ahead of the BISG’s forecast, but that only pushes up the schedule. Keep in mind that growth here is measured in revenue, which keeps the trend in the plus column. For unit sales, not dollar amounts, the numbers look bleak. In a year with no Potter, BISG estimated that total unit sales of juvenile books would fall 13 million, from 919 to 906 million. Sales would jump again when cloth and paper editions of the next Potter arrive, but after that, unit sales would tumble a stunning 42 million copies. If Harry Potter did spark a reinvigoration of reading, young adult sales would rise across the board, but while the Harry Potter fandom continues, the reading habit hasn’t expanded.

The headlong rush for Harry Potter, then, has a vexing counterpart: a steady withdrawal from other books. The results of

Reading at Risk

supply stark testimony to the definitive swing in youth leisure and interests. The report derives from the latest

Survey of Public Participation in the Arts,

which the National Endowment for the Arts designed and the U.S. Bureau of the Census executed in 2002. More than 17,000 adults answered questions about their enjoyment of the arts and literature (an impressive 70 percent response rate), and the sample gave proportionate representation to the U.S. population in terms of age, race, gender, region, income, and education.

Reading at Risk

supply stark testimony to the definitive swing in youth leisure and interests. The report derives from the latest

Survey of Public Participation in the Arts,

which the National Endowment for the Arts designed and the U.S. Bureau of the Census executed in 2002. More than 17,000 adults answered questions about their enjoyment of the arts and literature (an impressive 70 percent response rate), and the sample gave proportionate representation to the U.S. population in terms of age, race, gender, region, income, and education.

When the SPPA numbers first arrived and researchers compared them to results from 1982 and 1992, we found that most participations—for example, visiting a museum—had declined a few percentage points or so, not an insignificant change in art forms whose participation rates already hovered in the single digits. The existing percentage of people reading literature stood much higher, but the trend in reading literature, it turned out, was much worse than trends in the other arts. From 1982 to 2002, reading rates fell through the floor. The youngest cohort suffered the biggest drop, indicating something unusual happening to young adults and their relationship to books. The numbers deserved more scrutiny, and Dana Gioia, chairman of the Endowment, ordered us to draft a separate report complete with tables and analyses.

The survey asked about voluntary reading, not reading required for work or school. We aimed to determine how people pass their leisure hours—what they want to do, not what they have to do—and we understood leisure choices as a key index of the state of the culture. The literature assigned in college courses divulges a lot about the aesthetics and ideology of the curriculum, but it doesn’t reveal the dispositions of the students, preferences that they’ll carry forward long after they’ve forgotten English 201. Young people have read literature on their own for a variety of reasons—diversion, escape, fantasy, moral instruction, peer pressure—and their likings have reflected their values and ambitions, as well as their prospects. A 14-year-old girl reading Nancy Drew in bed at night may not appear so significant a routine, but the accumulation of individual choices, the reading patterns of 60 million teens and young adults, steer the course of U.S. culture, even though they transpire outside the classroom and the workplace. A drastic shift in them is critical.

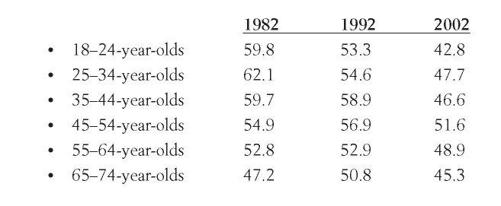

Here are the literary reader rates broken down by age:

A 17-point drop among the first group in such a basic and long-standing behavior isn’t just a youth trend. It’s an upheaval. The slide equals a 28 percent rate of decline, which cannot be interpreted as a temporary shift or as a typical drift in the ebb and flow of the leisure habits of youth. If all adults in the United States followed the same pattern, literary culture would collapse. If young adults abandoned a product in another consumer realm at the same rate, say, cell phone usage, the marketing departments at Sprint and Nokia would shudder. The youngest adults, 18- to 24-year-olds, formed the second-strongest reading group in 1982. Now they form the weakest, and the decline is accelerating: a 6.5 fall in the first decade and a 10.5 plummet in ’92-’02.

It isn’t because the contexts for reading have eroded. Some 172,000 titles were published in 2005, putting to rest the opinion that boys and girls don’t read because they can’t find any appealing contemporary literature. Young Americans have the time and money to read, and books are plentiful, free on the Internet and in the library, and 50 cents apiece for Romance and Adventure paperbacks at used bookstores. School programs and “Get Caught Reading”-type campaigns urge teens to read all the time, and students know that reading skills determine their high-stakes test scores. But the retreat from books proceeds, and for more and more teens and 20-year-olds, fiction, poetry, and drama have absolutely no existence in their lives.

None at all. To qualify as a literary reader, all a respondent had to do was scan a single poem, play, short story, or novel in the previous 12 months outside of work or school. If a young woman read a fashion magazine and it contained a three-page story about a romantic adventure, and that was the only literary encounter she had all year, she fell into the literary reading column. A young man cruising the Internet who came across some hip-hop lyrics could answer the survey question “In the last 12 months, did you read any poetry?” with a “Yes.” We accepted any work of any quality and any length in any medium—book, newspaper, magazine, blog, Web page, or music CD insert. If respondents liked graphic novels and considered them “novels, ” they could respond accordingly. James Patterson qualified just as much as Henry James, Sue Grafton as much as Sylvia Plath. No high/low exclusions here, and no minimum requirements. The bar stood an inch off the ground.

And they didn’t turn off literature alone. Some commentators on

Reading at Risk

complained that the survey overemphasized fiction, poetry, and drama. Charles McGrath of the

New York Times,

for instance, regretted the “perplexing methodological error” that led us to “a definition of literature that appears both extremely elastic and, by eliminating nonfiction entirely, confoundingly narrow.”

The Atlantic Monthly

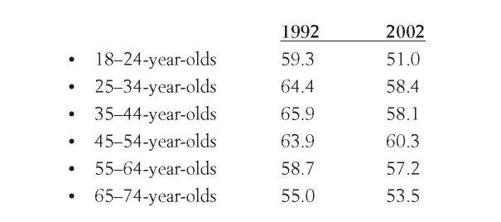

grumbled that the survey defined literature “somewhat snobbishly as fiction, plays, and poetry,” a strange complaint given that the questions accepted Stephen King and nursery rhymes as literature. Most important, though, the survey included general reading as well, the query asking, “With the exception of books required for work or school, did you read any books during the last 12 months?” Cookbooks, self-help, celebrity bios, sports, history . . . any book could do. Here, too, the drop was severe, with 18- to 24-year-olds leading the way.

Reading at Risk

complained that the survey overemphasized fiction, poetry, and drama. Charles McGrath of the

New York Times,

for instance, regretted the “perplexing methodological error” that led us to “a definition of literature that appears both extremely elastic and, by eliminating nonfiction entirely, confoundingly narrow.”

The Atlantic Monthly

grumbled that the survey defined literature “somewhat snobbishly as fiction, plays, and poetry,” a strange complaint given that the questions accepted Stephen King and nursery rhymes as literature. Most important, though, the survey included general reading as well, the query asking, “With the exception of books required for work or school, did you read any books during the last 12 months?” Cookbooks, self-help, celebrity bios, sports, history . . . any book could do. Here, too, the drop was severe, with 18- to 24-year-olds leading the way.

The general book decline for young adults matches the decline in literary reading for the same period, 8.3 points to 10.5 points. The comparison with older age groups holds as well, with young adults nearly doubling the book-reading change for the entire population, which fell from 60.9 percent in 1992 to 56.6 percent in 2002.

The Atlantic Monthly

found the lower figure promising: “The picture seems less dire, however, when one considers that the reading of all books, nonfiction included, dropped by only four points over the past decade—suggesting that readers’ tastes are increasingly turning toward nonfiction.” In fact, the survey suggests no such thing. That book reading fell less than literary reading doesn’t mean that readers dropped

The Joy Luck Club

and picked up Howard Stern’s

Private Parts.

It means that they dropped both genres, one at a slower pace than the other. And in both, young adults far outpaced their elders. The 8.3-point slide in book reading by 18- to 24-year-olds averages out to a loss of 60,000 book readers per year.

The Atlantic Monthly

found the lower figure promising: “The picture seems less dire, however, when one considers that the reading of all books, nonfiction included, dropped by only four points over the past decade—suggesting that readers’ tastes are increasingly turning toward nonfiction.” In fact, the survey suggests no such thing. That book reading fell less than literary reading doesn’t mean that readers dropped

The Joy Luck Club

and picked up Howard Stern’s

Private Parts.

It means that they dropped both genres, one at a slower pace than the other. And in both, young adults far outpaced their elders. The 8.3-point slide in book reading by 18- to 24-year-olds averages out to a loss of 60,000 book readers per year.

The same reading discrepancy between young adults and older Americans shows up in the latest

American Time Use Surveys

(ATUS), sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. ATUS asks respondents to keep a diary of their leisure, work, home, and school activities during a particular day of the week, and “oversamples” weekend tallies to ensure accurate averages. In the first ATUS, whose results were collected in 2003, the total population of 15-year-olds and older averaged about 22 minutes a day in a reading activity of any kind. The youngest group, though, 15- to 24-year-olds, came up at barely one-third the rate, around eight minutes per day (.14 hours). They enjoyed more than five hours per day of free time, and they logged more than two hours of television. The boys put in 48 minutes playing games and computers for fun—they had almost an hour more leisure time than girls, mainly because girls have greater sibling and child-care duties—and both sexes passed an hour in socializing. Of all the sports and leisure activities measured, reading came in last. Moreover, in the Bureau of Labor Statistics design, “reading” signified just about any pursuit with a text: Harry Potter on the bus, a story on last night’s basketball game on

,

or the back of the cereal box during breakfast. We should consider, too, that reading is easier to carry out than all the other leisure activities included in ATUS except “Relaxing/thinking. ” It costs less than cable television and video games, it doesn’t require a membership fee (like the gym), and you can still read in places where cell phones are restricted and friends don’t congregate. Nevertheless, it can’t compete with the others. The meager reading rate held up in the next two ATUS surveys. In 2005, 15- to 24-year-olds came in at around eight minutes on weekdays, nine minutes on weekends, while the overall average was 20 minutes on weekdays and 27 minutes on weekends.

American Time Use Surveys

(ATUS), sponsored by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. ATUS asks respondents to keep a diary of their leisure, work, home, and school activities during a particular day of the week, and “oversamples” weekend tallies to ensure accurate averages. In the first ATUS, whose results were collected in 2003, the total population of 15-year-olds and older averaged about 22 minutes a day in a reading activity of any kind. The youngest group, though, 15- to 24-year-olds, came up at barely one-third the rate, around eight minutes per day (.14 hours). They enjoyed more than five hours per day of free time, and they logged more than two hours of television. The boys put in 48 minutes playing games and computers for fun—they had almost an hour more leisure time than girls, mainly because girls have greater sibling and child-care duties—and both sexes passed an hour in socializing. Of all the sports and leisure activities measured, reading came in last. Moreover, in the Bureau of Labor Statistics design, “reading” signified just about any pursuit with a text: Harry Potter on the bus, a story on last night’s basketball game on

,

or the back of the cereal box during breakfast. We should consider, too, that reading is easier to carry out than all the other leisure activities included in ATUS except “Relaxing/thinking. ” It costs less than cable television and video games, it doesn’t require a membership fee (like the gym), and you can still read in places where cell phones are restricted and friends don’t congregate. Nevertheless, it can’t compete with the others. The meager reading rate held up in the next two ATUS surveys. In 2005, 15- to 24-year-olds came in at around eight minutes on weekdays, nine minutes on weekends, while the overall average was 20 minutes on weekdays and 27 minutes on weekends.

Other books

Date With Death (Welcome To Hell) by Langlais, Eve

Stripped by Hunter, Adriana

Blood Hound by Tanya Landman

Deeper by Blue Ashcroft

The Education of Madeline by Beth Williamson

ON EDGE (Decorah Security) by York, Rebecca

Under His Spell by Natasha Logan

All I Desire is Steven by James L. Craig

Follow Me Down by Tanya Byrne