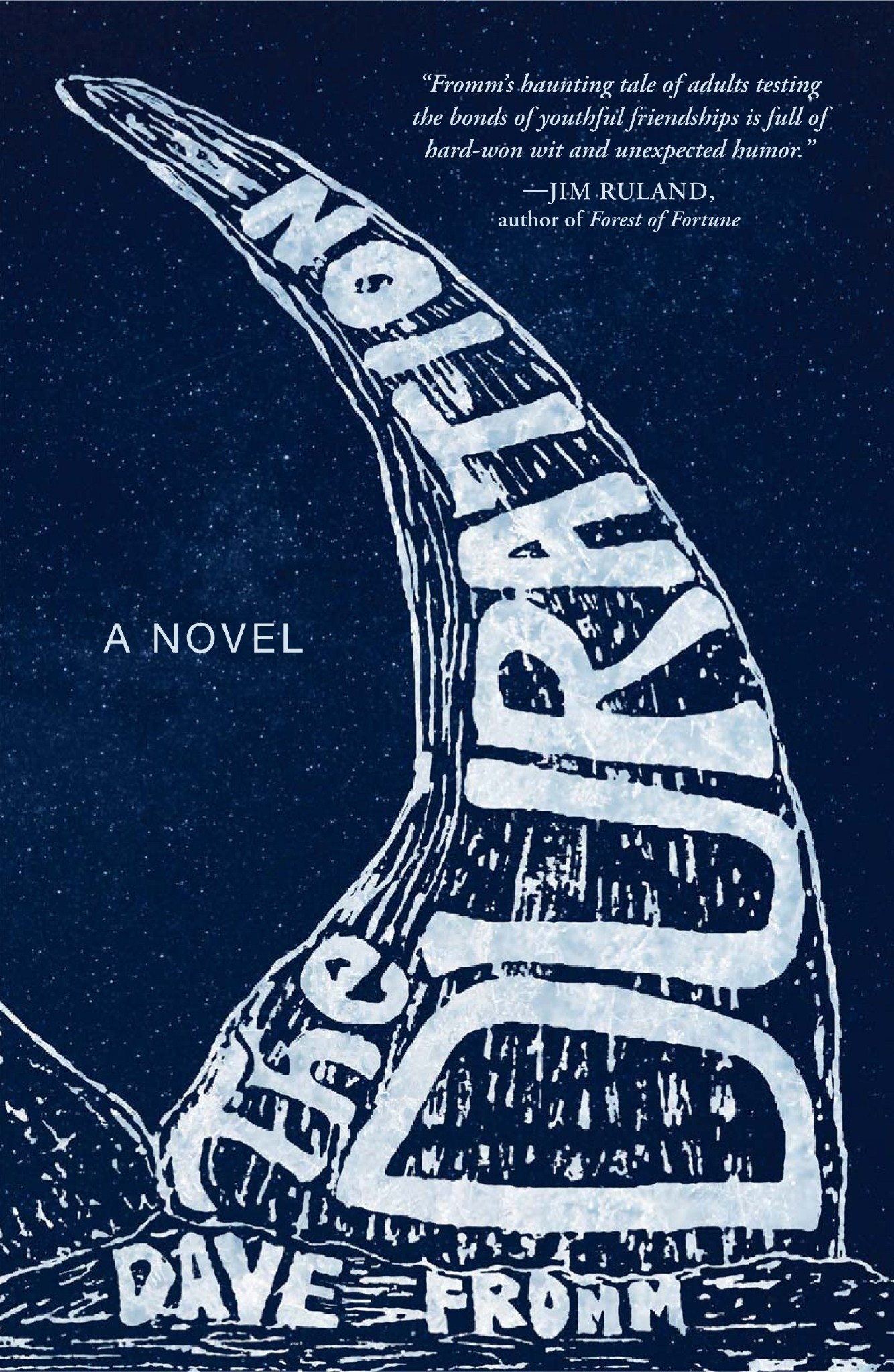

The Duration

Authors: Dave Fromm

A Novel

Dave Fromm

Copyright © 2016 by Dave Fromm.

All rights reserved.

This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher; exceptions are made for brief excerpts used in published reviews.

Published by

TYRUS BOOKS

an imprint of F+W Media, Inc.

10151 Carver Road, Suite 200

Blue Ash, OH 45242. U.S.A.

Hardcover ISBN 10: 1-4405-9464-3

Hardcover ISBN 13: 978-1-4405-9464-9

Paperback ISBN 10: 1-4405-9463-5

Paperback ISBN 13: 978-1-4405-9463-2

eISBN 10: 1-4405-9465-1

eISBN 13: 978-1-4405-9465-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fromm, Dave, author.

The Duration / Dave Fromm.

Blue Ash, OH: Tyrus Books, [2016]

LCCN 2015043825 (print) | LCCN 2015046242 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440594649 (hc) | ISBN 1440594643 (hc) | ISBN 9781440594632 (pb) | ISBN 1440594635 (pb) | ISBN 9781440594656 (ebook) | ISBN 1440594651 (ebook)

BISAC: FICTION / Literary.

LCC PS3606.R633 D87 2016 (print) | LCC PS3606.R633 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015043825

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, corporations, institutions, organizations, events, or locales in this novel are either the product of the author's imagination or, if real, used fictitiously. The resemblance of any character to actual persons (living or dead) is entirely coincidental.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and F+W Media, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters.

Cover design by Erin Alexander.

Cover images © Adrian Kollar/Olga Miltsova/123RF.

For Katie K.

"Can't be too picky in the deep."

Bob Schneider, "The Effect"

This is a work of fiction. While it uses real and perhaps recognizable places as settings, any similarities to actual people or events are entirely coincidentalâ

except

, that is, for the book's central secret, which is in fact based on an old Berkshire County mystery. Don't ask me to tell you what I think about it, though. It's a mystery, and you shouldn't believe anybody who claims to know the truth.

- Title Page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Author's Note

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- Acknowledgements

- The Legend of Columbus

- About the Author

“You promised,” Kelly said. “Two years.”

We were sitting in that coffeehouse on the corner of Columbus and Clarendon. It was a freezing winter Sunday. Dressed in travel section attireâsweats and sneaks, bed-headed. I was stubbly. Kelly's long hair was pulled back from her forehead by a sort of wide headband, then pulled again, farther back, into a severe ponytail. Wrangle that shit, kiddo. Show it who's boss. The coffeehouse, an anti-Starbucks catering to the same South End crowd willing to spend $5 on a latte, was the sort of place I liked to mock while still frequenting. Their pumpkin muffins were obsceneâeach one a boulder of orange dough, big as your head, that left oil stains soaking through the to-go bag; sometimes they dropped a few green pumpkinseeds on the top to pretend it was a saladâand I'd sworn on several occasions, usually just after finishing one, to never eat another. Course, I was about to bust into one right then.

I frowned and broke a soft little wedge off the muffin boulder to buy time. Two years? I don't think I would have agreed to that. Two years was a blink. You'd have to suffer something a lot longer before you gave up on it.

But Kelly was resolute.

“Right up on that corner,” she said, pointing out toward Dartmouth without looking. “You said we'd give it two years here and if it wasn't working we'd reconsider.”

She was probably paraphrasing, but probably right all the same. Up there, where Dartmouth hit Columbus, where the kegs rolled into the service entrance at the back of Cleary's and they had live music every Thursday and you could buy a mammoth cheeseburger at the takeaway place next door, I'd said a lot of things. Kelly wasn't the cheeseburger type, but we'd stumbled home together more than a few times, hand-in-hand, flush with the inebriants of one's upper twenties, one's first semi-domestic arrangement, plus, most likely, plenty of other inebriants, and I was probably thinking about putting the moves on her when we got back to the apartment, three narrow flights up, stumbling and crawling and laughing, hopefully, and maybe I'd even start the moves before we gained the landing, depending on what sort of attire she was sporting and how hard it was to find my keys, and anyway I could imagine at moments like that saying whatever it was I thought she wanted to hear. And I'd probably even meant it at the time.

They called me from the counter. Two lattes for Pete. Pete Johansson, Pete So Handsome, your mother's answered prayer. Best days behind me, but barely. I got the lattes and doused them with sugar, or doused mine at least, grateful for a reprieve.

I knew, vaguely, that she was unhappy. But, shit, we're all vaguely unhappy. That's just the human condition, right?

Something about not loving Boston. As if that were possible. What's not to love? She'd run her diagnostics at bedtime, softening the invective with toothpaste. These people. Six months out of the year, she'd say, everyone pops their parkas out like that

South Park

character who was always dying, and the other six months they walk around with big chips on pale, freckled shoulders. You can even see the chips under the parkas, she'd say. I loved watching her brush her teeth. The rich ones look like horses, she'd say, and the poor ones look like donuts. They have two interpersonal settingsâresentment and overfamiliarity. They hate you until they love you and then they won't stop.

Something like that.

I came back to the table, sugar-fortified, sat down.

“I don't think I said two years,” I said, pausing, watching her eyes flatten. I looked away quickly, before she could turn them to me. This line of attack had to be rethought. “And even if I did, look, promises are like sunk costs, right? That one, whether or not I made it, I made it two years ago. That's forever ago. We've invested here. We have equity now.”

I was thinking of our jobs, our lease, the people we nodded to on the street who were little more than strangers we kept seeing over and over again, but who might, someday, if none of us ever moved on, become acquaintances. We need to operate from the present, the now. The market value of our accounts.

I was winging it, obviously, as I didn't truly understand economics. Or relationships, for that matter.

What was the market value of our accounts, anyway? I looked out the high front windows, onto the desolate and unlovely stretch of Columbus near the backside of the train station, a long block from Dartmouth. Brick nonprofits and parking garages, the wind curling up from the underground highway to spin leaves and trash and umbrellas into a vortex. Not glam. Our apartment was just a starter place, a rental, a foothold on the city. But we'd move on. Move on up, hopefully, like the Jeffersons did, to Newton or Back Bay or, maybe, who knew? Maybe Beacon Hill. Though those weren't really Jeffersons neighborhoods, this being stodgy Brahmin Boston after all. Whatever. We'd move around. Find new old coffeehouses, new Irish bars at which to cheer the Sox and boo the Yanks. Withstand new Januaries. Meet a whole new set of strangers.

But that sort of incremental stuff wasn't what Kelly was talking about. She was talking, again, about heading west. Like, way west. The West.

I reached for the muffin.

“If you don't stop eating that,” she said, “and look at me . . . ”

She left it blank and I tried to evaluate how much mileage I could get out of some sort of faux resistance to ultimatums, something defensible about, like, not negotiating with terrorists. I looked at her, but I kept eating the muffin. A man can be pushed only so far.

“What do you want?” I asked. “You want to just up and start over somewhere?”

That didn't seem rational to me. That seemed like, I don't know, something a certain kind of irrational person might propose with their certain kind of hysterical brain. You know what kind of person I mean? I mean, what about hard work? What about the nobility of suffering? Plus, it was winter, midwinter even, and it's never a good idea to undertake anything big, even big decisions, in winter. Tends to cut out nearly a third of the year, but still. Ask Napoleon.