The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 (15 page)

Read The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 Online

Authors: John Darwin

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Modern, #General, #World, #Political Science, #Colonialism & Post-Colonialism, #British History

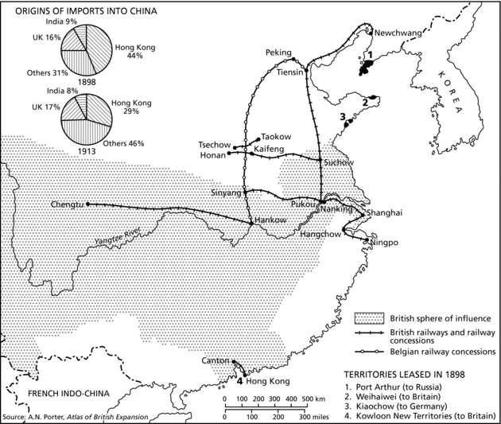

Map 5 Britain’s position in China, 1900

‘balanced’ by a British base at Wei-hai-wei in North China and the extension of Hong Kong into the ‘New Territories’. But Salisbury also tried to reduce the danger of friction with Russia (his main fear) by acknowledging her claim to priority in Manchuria in the Scott-Muraviev agreement in 1899. If Russia, as France's ally, had nothing to gain from quarrelling with Britain, so he reasoned, there was little danger of Anglo-French antagonism in the Near East and Africa spilling over into war. This was an approach already vindicated by the French retreat in the Fashoda crisis and the successful resolution of Anglo-French differences in West Africa. But, in the middle of 1900, as Britain became ever more deeply embroiled in the South African War, the Boxer Rising and its xenophobic challenge to all foreign interests in China threatened to unite Britain's rivals in a general partition of the Ch’ing empire. ‘Her Majesty's Government’, Salisbury told his minister at Peking with gloomy understatement, ‘view with uneasiness a “concert of Europe” in China.’

52

As it turned out, the Chinese were too resilient and the Europeans too divided to permit a replay of the African partition. Japan's victory over Russia in 1905 removed a Chinese share-out from the European diplomatic agenda. But the Boxer crisis in 1900 had brought the new geopolitics of British power to a climax. It signalled the birth of what became the grand dilemma of imperial strategy in the twentieth century: how to safeguard British interests simultaneously in Europe, the Middle East and East Asia. With the great enlargement of scale brought by the new wave of rivalry and confrontation in Asia and the Pacific, Salisbury's delicate system of checks, balances, blandishments and threats, with its pivot in Egypt, seemed to have reached its term. In the world now imagined by Pearson, Kidd and Mackinder, and by Chamberlain, Milner or Curzon, old diplomacy was not enough. The tide of world politics, that had run so long in Britain's favour, now seemed to have turned against her.

Managing empire

Managing a worldwide empire under these new conditions threw a heavy burden of political management onto administrative institutions in London that had grown up haphazardly since the early part of the century. ‘The external affairs of Great Britain’, remarked a sarcastic observer, ‘are distributed without system between the Foreign, Colonial and India Offices. Their provinces overlap and intersect each other…like the divisions of some of the northern counties of Scotland.’

53

In fact, responsibility for the faraway spheres of rule and influence that made up the British system was scattered across half a dozen departments. The shadow of the Treasury with its ‘Gladstonian garrison’ of bureaucratic skinflints lay over them all. The Foreign Office enjoyed primacy in external affairs as the guardian of Britain's stake in the cockpits of Europe – the centre of the world. It supervised relations in the ‘informal empire’ including Egypt (even after its occupation in 1882), the Sudan (even after conquest in 1898), China and the early protectorates in West and East Africa. The Colonial Office ruled over a jumble of ‘crown colonies’ (where local representatives had an advisory role at best), dependencies and protectorates; and reigned over the self-governing settler colonies, who resented this

mésalliance.

In the Mediterranean, parts of tropical Africa and even in China (Hong Kong was a crown colony) it was the recalcitrant junior partner of the Foreign Office, with its own view of priorities. The India Office had been constructed in 1858 out of the East India Company and the old Board of Control to preside over an Indian ‘empire’ enlarged by 1885 to include all of Burma as well western outposts in the Persian Gulf and at Aden. Control over imperial defence lay with the Admiralty and the War Office. The former regarded itself (like the Foreign Office) as the real guarantor of imperial safety and despised the army as a motley of colonial garrisons without strategic value.

Of course, the vast proportion of public business in the colonies and India lay ‘below the line’ and never came to the attention of officials or ministers in London. The self-governing colonies were almost entirely exempt from imperial scrutiny. In theory, the Colonial Office could disallow their legislation if it was deemed to infringe the imperial prerogative in external affairs, defence or constitutional change. In practice, this power was rarely needed and hardly ever used. Crown colony governors reported to the Office, but, even with the telegraph (still very expensive) and more frequent mails, its officials were ill-equipped to oversee their rule. Colonial governors were, by convention, masters in their own house. They could be rebuked or recalled for misdemeanours or acting

ultra vires

, but, provided they stayed solvent, kept order and avoided war, remote control from London was lax. The Colonial Office acted more as a regulator, monitoring colonial laws, expenditure and personnel, than as a policy-making department, certainly before Joseph Chamberlain's arrival in 1895.

54

Much the same was true of the India Office, which faced a single ‘super-governor’ in the Viceroy. The Viceroy, selected almost invariably from the political elite at home, not from the ranks of British officialdom in India, had his own network of political friends, and his status approached that of a cabinet minister. As a temporary autocrat of tsar-like magnificence, the liege-lord of 600 feudatory states and an Asian ruler with his own army and diplomatic service (for India's frontier regions), he was hard to coerce and practically irremovable.

55

The vast stream of paper that poured westward annually to fill the archives of the India Office was less a measure of its control than a relic of Parliament's obsession since the age of Burke with the misuse of Indian revenues by the home government for patronage or foreign war. In fact, the torrent of administrative minutiae enthusiastically supplied by Calcutta dulled parliamentary curiosity about India to the point of anaesthesia – and was meant to.

56

The formal debates on the Indian budget were notoriously ill-attended.

Despite this pattern of devolution by accident and design, there were many issues that rose ‘above the line’ and required a decision in London. Any serious breakdown of internal order would mean reinforcing the colonial garrison from the pool of British infantry battalions – the reserve currency of imperial power. Using up this scarce resource (much of it already deployed in India) raised awkward questions about the balance between British commitments in Asia, North America, the Mediterranean and Southern Africa. Any constitutional alteration had to be inspected in case it implied new costs for the British taxpayer or had implications for other dependencies or imperial defence. Action by a colonial government which impeded British trade invariably set off an alarm at Westminster. London had to swallow the tariffs imposed by self-governing colonies, but vetoed any attack on free trade in India and the dependencies. Any aspect of imperial rule, or of the advancement of British interests in the informal empire, which produced international complications and raised the prospect, however remote, of conflict with a European power, attracted immediate scrutiny in London. More than anything else, it was the addition of new imperial liabilities carrying higher costs and the risk of friction with rival powers which exercised policy-makers in the late-Victorian period.

As a result, the problem of imperial expansion has come to be the main window through which we peer at the late-Victorian idea of empire. It raised in an acute form the question of what purpose the formal empire and the larger British system were meant to serve, on what grounds they should be extended, and for whose benefit. The response of British leaders was bound to reflect, however subliminally, their understanding of world politics, their notions of strategy, their grasp of economic realities, their views of race and culture, their sense of national community, their hopes of expansion and fears of decline. The tortuous decision-making imposed by conflicting priorities at home and abroad and the periodic sense of crisis, gives a powerful insight into the mechanisms through which primacy in a huge and unwieldy world-system was reconciled with representative government in an age of growing social anxiety. Indeed, the intricate connection sometimes revealed between domestic politics and imperial policy raises the hardest question of all: how far Britain had become by 1900 an ‘imperialised’ society, founding its values, culture and social hierarchy mainly upon its role as the centre of an imperial system.

57

Not surprisingly, the process by which the central issues of imperial expansion were resolved politically has long been the focus of an intense debate. The older historians of late-Victorian imperialism emphasised crude motives of economic gain, diplomatic prestige, racial arrogance or electoral calculation as the dynamic behind the willingness of successive British governments to extend the formal empire of rule, practise the diplomacy of brinkmanship in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and China, and resort to a costly and humiliating colonial war in 1899. But, since the 1960s, explanation has been dominated by the powerful model put forward by Robinson and Gallagher and taken up by a large school of disciples.

58

Robinson and Gallagher rejected most previous explanations as naïve conjecture or special pleading. They insisted that the motives for imperial aggrandisement had to be sought in the largely private thoughts and calculations of the decision-making elite who sanctioned territorial advance and chose between the forward policies that were urged upon them. They denied that the documentary evidence revealed any serious pursuit of economic goals and claimed instead that the overwhelming motive for intervention, annexation and acquisition was strategic: to defend the territories and spheres accumulated in the flush times of mid-century, above all the vast, valuable, vulnerable empire in India.

This conclusion, resting upon a close study of the African partition, was also based upon a radical reinterpretation of the place of empire in British politics and the outlook of the ruling elite. Whereas previous writers had stressed the growth of ‘popular’ imperialism and the anxious desire of party leaders to propitiate it with jingo excess, Robinson and Gallagher argued that public attitudes towards empire were mainly shaped by dislike of the financial burden it implied and distaste for the moral risks it imposed. The best kind of empire was informal (and therefore free from patronage), costless and peaceful. Expansion might be tolerated if it recouped its expenses and avoided disaster. But the Midlothian election in 1880 showed how the electorate would punish a government caught red-handed in imperial misadventure. Thereafter, they argued, ministers would only agree to a forward policy

in extremis

, as a painful remedy to stave off the general attrition of their world-system and its defences. Far from bowing to popular pressure or the pleading of commercial and financial interests, the ‘official mind’ – a key concept in their model – based its grudging decisions to advance on gloomy estimates of strategic and electoral danger. They mistrusted jingoism on principle and loathed all forms of imperial enthusiasm. The policy-makers’ rule of thumb decreed that, far from staging a forward march from the bastions of mid-Victorian imperialism, the British were condemned by secular change to run faster to stay in the same place.

In other hands, this ironic portrait of late-Victorian high policy broadened into a definitive view of British imperialism after the turning point of 1880. Reactive, defensive, gloomily conservative, it was built on regret for the golden age of mid-Victorian primacy and obsessive concern for the protection of India. Britain was a

status quo

power drawn into reluctant expansion by the crises in her spheres of influence, felt most acutely where strategic not economic interests were at stake.

59

But, at the height of its influence, this ‘pessimistic’ interpretation was robustly challenged in a critique which pointed unerringly to its least plausible components. These were the implication that the mid-Victorian era had seen the apogee of British imperial power; the suggestion that late-Victorian expansion was economically sterile; and the view of the policy-makers as a Platonic elite guided by abstract principles of national interest. Cain and Hopkins

60

insisted instead that politicians, officials and the commercial and financial world of the City of London were united by a common ethos of ‘gentlemanly capitalism’. The Victorian ruling elite sprang from a marriage of landed and commercial (not industrial) wealth, and its members were to be found as much in banks and finance houses as in Whitehall or the Houses of Parliament. A common education, shared values and linked fortunes meant that governments and their advisers were instinctively sympathetic to the interests of trade, but especially finance. The key decisions of late-Victorian forward policy, like the occupation of Egypt in 1882, the policy of spheres in China and the war against the Boers in 1899, were taken not on strategic criteria but to promote (or defend) Britain's financial stake. Far from marking the gloomy defence of a reduced inheritance, imperial assertiveness reflected an aggressive commercial and financial expansion and the deliberate channelling of new economic energy into a periphery which had to be ‘remade’ for the purpose. And behind this advance stood not a doubting, sceptical public opinion but a powerful vested interest enthroned at the heart of government.