The Empty Throne (The Warrior Chronicles, Book 8)

Read The Empty Throne (The Warrior Chronicles, Book 8) Online

Authors: Bernard Cornwell

Published by HarperCollins

Publishers

Ltd

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

First published by HarperCollins

Publishers

2014

Copyright © Bernard Cornwell 2014

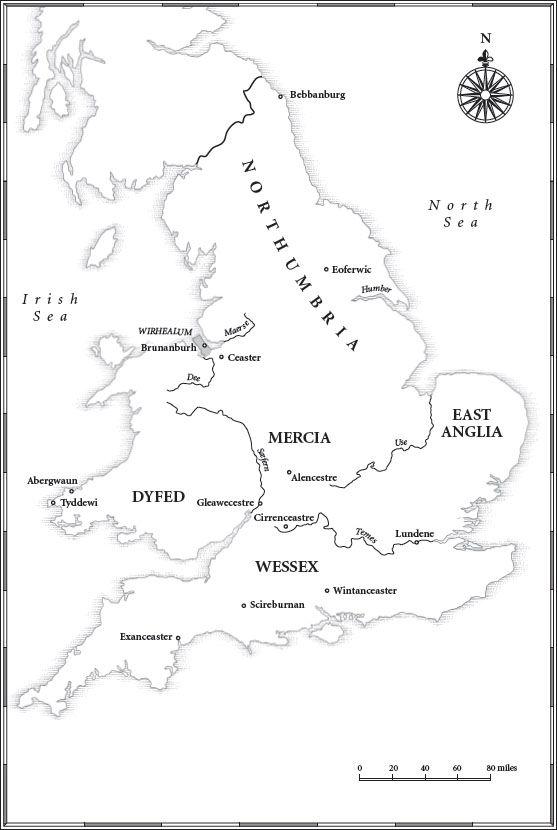

Maps © John Gilkes 2014

Bernard Cornwell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007504169

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007504183

Version: 2014-09-16

For Peggy Davis

Contents

The spelling of place names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the

Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names

or the

Cambridge Dictionary of English Place-Names

for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign,

AD

871–899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; preferring the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

| Abergwaun | Fishguard, Pembrokeshire |

| Alencestre | Alcester, Warwickshire |

| Beamfleot | Benfleet, Essex |

| Bebbanburg | Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland |

| Brunanburh | Bromborough, Cheshire |

| Cadum | Caen, Normandy |

| Ceaster | Chester, Cheshire |

| Cirrenceastre | Cirencester, Gloucestershire |

| Cracgelad | Cricklade, Wiltshire |

| Cumbraland | Cumbria |

| Defnascir | Devonshire |

| Eoferwic | York |

| Eveshomme | Evesham, Worcestershire |

| Fagranforda | Fairford, Gloucestershire |

| Fearnhamme | Farnham, Surrey |

| Gleawecestre | Gloucester, Gloucestershire |

| Lundene | London |

| Lundi | Lundy Island, Devon |

| Mærse | River Mersey |

| Neustria | Westernmost province of Frankia, including Normandy |

| Sæfern | River Severn |

| Scireburnan | Sherborne, Dorset |

| Sealtwic | Droitwich, Worcestershire |

| Teotanheale | Tettenhall, West Midlands |

| Thornsæta | Dorset |

| Tyddewi | St Davids, Pembrokeshire |

| Wiltunscir | Wiltshire |

| Wintanceaster | Winchester, Hampshire |

| Wirhealum | The Wirral, Cheshire |

My name is Uhtred. I am the son of Uhtred, who was the son of Uhtred, and his father was also called Uhtred. My father wrote his name thus, Uhtred, but I have seen the name written as Utred, Ughtred or even Ootred. Some of those names are on ancient parchments which declare that Uhtred, son of Uhtred and grandson of Uhtred, is the lawful, sole and eternal owner of the lands that are carefully marked by stones and by dykes, by oaks and by ash, by marsh and by sea. That land is in the north of the country we have learned to call Englaland. They are wave-beaten lands beneath a wind-driven sky. It is the land we call Bebbanburg.

I did not see Bebbanburg till I was grown, and the first time we attacked its high walls we failed. My father’s cousin ruled the great fortress then. His father had stolen it from my father. It was a bloodfeud. The church tried to stop the feud, saying the enemy of all Saxon Christians was the pagan Northmen, whether Danish or Norse, but my father swore me to the feud. If I had refused the oath he would have disinherited me, just as he disinherited and disowned my older brother, not because my brother would not pursue the feud, but because he became a Christian priest. I was once named Osbert, but when my elder brother became a priest I was given his name. My name is Uhtred of Bebbanburg.

My father was a pagan, a warlord, and frightening. He often told me he was frightened of his own father, but I cannot believe it because nothing seemed to frighten him. Many folk claim that our country would be called Daneland and we would all be worshipping Thor and Woden if it had not been for my father, and that is true. True and strange because he hated the Christian god, calling him ‘the nailed god’, yet despite his hatred he spent the greatest part of his life fighting against the pagans. The church will not admit that Englaland exists because of my father, claiming that it was made and won by Christian warriors, but the folk of Englaland know the truth. My father should have been called Uhtred of Englaland.

Yet in the year of our Lord 911 there was no Englaland. There was Wessex and Mercia and East Anglia and Northumbria, and as the winter turned to a sullen spring in that year I was on the border of Mercia and Northumbria in thickly wooded country north of the River Mærse. There were thirty-eight of us, all well mounted and all waiting among the winter-bare branches of a high wood. Beneath us was a valley in which a small fast stream flowed south, and where frost lingered in deep-shadowed gullies. The valley was empty, though just moments before some sixty-five riders had followed the stream southwards and then vanished where the valley and its stream turned sharply west. ‘Not long now,’ Rædwald said.

That was just nervousness and I made no answer. I was nervous too, but tried not to show it. Instead I imagined what my father would have done. He would have been hunched in the saddle, glowering and motionless, and so I hunched in my saddle and stared fixedly into the valley. I touched the hilt of my sword.

She was called Raven-Beak. I suppose she had another name before that because she had belonged to Sigurd Thorrson, and he must have given her a name though I never did find out what it was. At first I thought the sword was called Vlfberht because that strange name was inscribed on the blade in big letters. It looked like this: