The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness

Read The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness Online

Authors: Rebecca Solnit

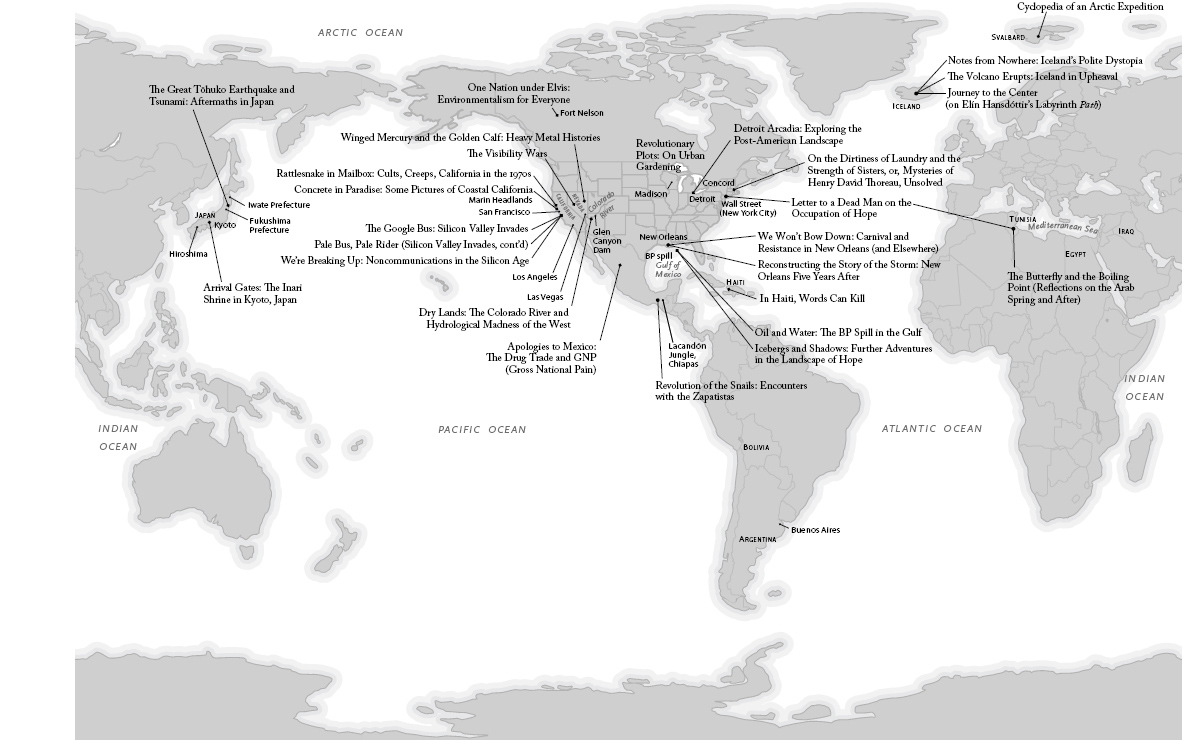

A Geographical Index

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF TROUBLE AND SPACIOUSNESS

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright © 2014 by Rebecca Solnit

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Jacket design by David Bullen

Book design by BookMatters, Berkeley, California

Cover art: Rebecca Solnit, Rome, Italy, 2009,

courtesy of FameFlynet Pictures

World map created by Ben Pease/Pease Press using

indiemapper.com

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ANSI

39.48–1992.

Cataloging-in-Publication data on file at the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-59534-199-0 ebook

18

17

16

15

14

|

5

4

3

2

1

CONTENTS

Introduction: Icebergs and Laundry

A

Cyclopedia of an

A

rctic Expedition

B

The

B

utterfly and the

B

oiling Point

Reflections on the Arab Spring and After

C

ults,

C

reeps,

C

alifornia in the 1970s

Some Pictures of Coastal

C

alifornia

The

C

olorado River and Hydrological Madness of the West

Exploring the Post-American Landscape

G

Winged Mercury and the

G

olden Calf

Further Adventures in the Landscape of

H

ope

I

I

nside Out, or

I

nterior Space

J

The Great Tōhoku Earthquake and Tsunami

The Inari Shrine in Kyoto,

J

apan

(on Elín Hansdóttir’s Labyrinth

Path

)

L

L

etter to a Dead Man on the Occupation of Hope

The Drug Trade and GNP (Gross National Pain)

N

Reconstructing the Story of the Storm

Carnival and Resistance in

N

ew Orleans

Noncommunications in the

S

ilicon Age

S

ilicon Valley Invades, Cont’d

T

On the Dirtiness of Laundry and the Strength of Sisters

Or, Mysteries of Henry David

T

horeau, Unsolved

That thing we call a place is the intersection of many changing forces passing through, whirling around, mixing, dissolving, and exploding in a fixed location. To write about a place is to acknowledge that phenomena often treated separately—ecology, democracy, culture, storytelling, urban design, individual life histories and collective endeavors—coexist. They coexist geographically, spatially, in place, and to understand a place is to engage with braided narratives and sui generis explorations.

This is a book about places, which is to say it’s about those many forces in combination. About Shinto landscape in Japan, about yearnings for and intermittent realizations of justice and democracy in northern Africa and Iceland and the United States, about the way Yankee drug consumption is devastating Mexico (in an essay that I first pictured as a map showing pain being outsourced the way labor and toxic waste are outsourced to poorer countries), about why we are obsessed with gardening right now, about what environmentalists got wrong about country music and nearly everyone got wrong about Henry David Thoreau’s laundry, about technology and amnesia in San Francisco. And it’s about the places themselves: the orange of those Shinto gates, the blue of icebergs, about dancing in the streets of New Orleans, and occupying in the streets of New York.

I think of myself as a San Franciscan, a Californian, and a Westerner, three concentric rings that have enclosed many of my earlier projects. But when I put together the essays in

The Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness

, I was surprised to survey the breadth of my travels: I’d been reporting from the Arctic to Mexico, from Japan to Detroit to Occupy Wall Street. A few things led me out of my region.

One was that in the Bush era, every American seemed saddled with the

weight of the world; our country was in Afghanistan and Iraq (and had, as it did before and does now, about 1,000 military bases around the world and a disproportionate role not only in climate change but also in sabotaging international agreements to do something about it). I was compelled to become a public citizen and to think about broad issues—hope, civil society, revolution, climate—and the questions these subjects raised had answers and ideas cached across the globe.

But it wasn’t only responsibility that took me afar; it was invitations and curiosity. I had always wanted to go to the far north, and invitations to go to Iceland in 2008 and Svalbard in the farthest north in 2011 were taken up with alacrity. The latter place fulfilled my wildest desires for northernness, but Iceland turned out to be a complicated political powder keg that would explode not long after I wrote about it. (My first piece on Iceland included in this anthology appeared about two weeks before the country’s economy collapsed and its population rebelled. During those two weeks I was told that I’d been harsh on a country that had managed to craft a very pretty image of itself; afterward I never heard that again. I only regret that I wasn’t able to cover Iceland’s next five years of glorious political experimentation—which faded in spring of 2013, when Icelanders reelected the neoliberals who destroyed the economy in the first place, like a wife going back to her abusive husband.)