The End of Sparta (2 page)

Authors: Victor Davis Hanson

A Historical Postscript

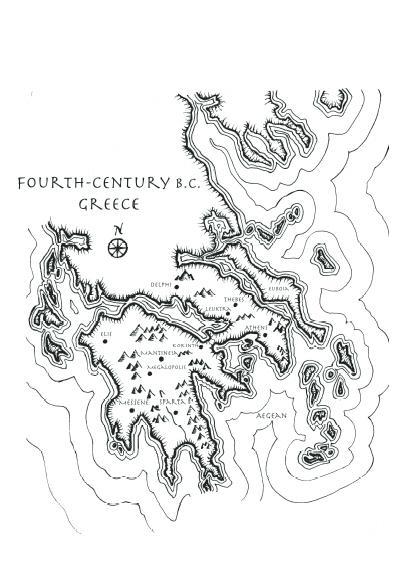

The Peoples and Places of Fourth-Century B.C. Greece

Principal Characters

Timeline

Footnote

A Note on the Author

By the Same Author

Imprint

This is the story of the great march against Sparta, the dream of the general Epaminondas of classical Thebes, whom the ancient Greeks and Romans acclaimed as the greatest man the classical world produced. Today we hear little of him. We know even less about all that his armies accomplished in a dramatic two-year period between 371 and 369 B.C.

Most contemporary accounts of that war were long ago lost. Our few extant historians apparently did not like the Thebans and so often misrepresented them or left them out of their narratives entirely. Most often Greek writers focused instead on Sparta and Athens. All that helps to explain why Epaminondas has faded from our memories—and why I offer a novel about what he accomplished.

Sometime in July 371 B.C., the Theban Epaminondas and his Boiotian Greeks shattered the phalanx of the supposedly invincible Spartans at the battle of Leuktra. They killed the Spartan king Kleombrotos, and crushed his warrior elite. The next year, not content with that stunning victory, Epaminondas—a follower of the philosopher Pythagoras who believed that our souls lived beyond our bodies and were judged by our deeds during our incarnate existence—led a grand coalition of Greeks southward to overrun Sparta.

The plan was to liberate the people of the Peloponnesos and apparently to reorder Greece itself. They were to found great citadels to hem in a weakened Sparta, and to free forever the serfs of its colony across the mountains in Messenia. That way, Epaminondas might cripple Sparta by robbing it of agricultural labor and thus ensure that no Greek people should be serfs to other Greeks—and that the Spartans, like other Greek militiamen, would finally have to grow their own food rather than train constantly for war.

Still, we cannot quite fathom all the reasons why tens of thousands followed this mystic general—plunder of course, strategic necessity probably, idealism perhaps. We only know that his preemptive invasion of the Peloponnesos began the end of Sparta—at least as the preeminent power as the Greeks had known it for centuries.

Nor do classical scholars understand the degree to which Pythagorean idealism energized these Theban liberators. Pythagoras was always a shadowy figure even to the Greeks. He had long been dead by the time of Epaminondas. Contemporaries derided Pythagoreans and their practices as a subversive cult. They certainly seemed strange. The embrace of vegetarianism, equality between the classes and sexes, reincarnation, reverence for nature’s harmony and order, avoidance of extremes, and fascination with numerical symmetries all frightened traditional Greeks. Apparently the soul could achieve its lasting perfection and rest only by denying the earthly appetites. It was almost considered trapped within matter of some sort—in cyclical fashion reentering a plant, an animal, or a human until it was cleansed of temptation, and at last set free to become incorporeal and immortal.

The divine was visible around us for those willing to train hard to appreciate it. Prime numbers cannot be divided. Man, not nature, creates artificial and unnatural notions of diet. Social intercourse and rank should be dissolved. Plants and animals have souls and are one with men and thus sacrosanct. Suppression of the ego and material acquisition alone help us to glimpse the godly.

For the Pythagorean farmer, the divine was found by cultivating symmetry out of savage chaos. For the statesmen, the ideal was to return men to their naturally free state without arbitrary rank. For the citizen, he should avoid eating meat and not be embarrassed of using the left—and traditionally unlucky—hand. Somehow for Epaminondas and his circle all that translated into an idealism of freeing the serfs of Sparta—or at least the philosophical veneer of a shrewd strategy to weaken rival Spartan military power.

The catalysts of this story of Epaminondas are the farmers of the clan of the Malgidai—Mêlon, his slaves Chiôn and Nêto, and their fellow rustics from the highland orchards and vineyards of Mt. Helikon. These characters—unlike most others in the novel—are not found in the historical record, but they are the sort of people who so often appear as farmers in the

Works and Days

of Hesiod, various comedies of Aristophanes, and the letters about rural life that have come down to us under the name of Alciphron.

A word is needed on the use of dialogue. How can Greek-speaking literary characters, belonging to a foreign world some 2,500 years past, sound authentically ancient and yet be understandable to a modern English reader?

Classical Greek authors themselves wrote in what we today might call a formal style. Their own elevated vocabulary and complex syntax certainly were not realistic, and would have been recognized as such by the proverbial man in the street. Indeed, both public orations and recorded private dialogue—whether found in Thucydides’s history, Plato’s repartee, or the verses of Sophocles—were not intended to reflect actual speech.

Much less did Greek prose mimic the spoken word heard daily in a Thebes or Athens. Even at their most colloquial expression, Greek literary prose and poetry were a world away from the accessibility of American popular slang.

So I have tried to strike a balance—avoiding both the extremes of the formal prose of nineteenth-century English historical fiction (written in large part by novelists who knew Greek and Latin and emulated the complex syntax of ancient authors), and the now common practice of making ancient people sound as if they were American suburbanites.

1

My editor at Bloomsbury Press, Peter Ginna, offered countless editorial suggestions that have improved the narrative. Glen Hartley and Lynn Chu of Writers’ Representative once again proved invaluable friends, advisors, and agents. I profited a great deal from close readings of the manuscript by Curtis Easton, Susannah Hanson, Jennifer Heyne, Raymond Ibrahim, Yishai Kabaker, and Bruce Thornton. I would also like to thank the editorial staff at Bloomsbury Press for editing, advice, and patience in bringing the book to fruition.

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

A cart approached raising a high dust trail. A few more hoplite soldiers for the outmanned army?

Atop the hill, in the center of the plain of Leuktra, a lookout man of Epaminondas was already yelling out the news. Proxenos, the Plataian, had spotted the wagon in the distance—but only one, a single-ox cart maybe, making its way up the switchbacks from the town of Thespiai. That surely meant Mêlon from Mt. Helikon had come to battle at Leuktra as he had promised. He was late, but here nonetheless for the final reckoning with the Spartans. And it looked as if he came with two other men as well.

“He’s here. Mêlon of Thespiai is here with Epaminondas, or least almost here.” Proxenos did not wait for the wagon to near. He ran down to the camp of Epaminondas to tell his generals that the apple, the

mêlon

of the Spartans’ dreaded prophecy had at last come to battle—as if the awaited man were now worth a thousand, if not five thousand at least. The presence of Mêlon, the apple, would win over the hesitant horsemen and the scared farmers and the ignorant tanners and potters as well. Could not the council start this very night and muster the army for battle? Oh yes, Proxenos thought, all the silly superstitious Boiotians would at last fight now. They would battle not for right or even their land, but buoyed by the idea they would destroy the Spartan army with this aging cripple of prophecy, Mêlon, son of Malgis, at their side and General Epaminondas at their front.

Mêlon saw ahead the lookout running down the hill, but made no point of it. He was in the back of the cart and stretched his legs out. The Thespian also ignored the singing of one of his slaves, Gorgos, beside him. Instead, he pointed to the other with the reins, Chiôn, to find the good ground and let old loud Gorgos be. Mêlon’s feet without sandals were now dangling from the open backside. His old, twisted leg was wrapped. He had bound it with leather straps for battle. Mêlon had wedged himself among the food and arms, propped up in the back of the deep cart—and had just woken up again, when a wheel jolted out of the stone ruts and slammed back in.

The groans of the ox Aias, as the wagon kept uphill a bit longer, had helped to rouse Mêlon from his dark returning dreams of a high mountain hut. The shack was not the one on his own farm on the uplands of Mt. Helikon. Not at all.

Instead, it was alien and had something to do with this impending war, and seemed to be shared somehow with Gorgos. But it was far away, cold—and, he sensed, to the dreaded south. How he wished the dream interpreter Hypnarchos were here, with his red-lettered scrolls that made sense of the nonsense of the night visions, and taught which dreams were false and which could prove true. In these apparitions, this shed was also shrouded in rain and winter fog, high in spruce trees somewhere amid the clouds. The hazy peaks around it were foreign, and not those of his Helikon. His Gorgos was there too, just as he was here now, still singing his Tyrtaios, but different looking and sounding as well. His other two slaves, Nêto and Chiôn, they were also in this far-away vision. He remembered that much and accepted that the dreams became more frequent as the war loomed closer.

But Mêlon was now fully awake and he sensed Gorgos was, too—likewise rousted from the same dream. Mêlon looked about Boiotia again as the wagon slowly creaked past the hill’s summit to a flat meadow. He saw no shed of his dreams anywhere, but he heard his name shouted by some guards off to the right. Otherwise, the cut grain fields were quiet and empty. Not a Spartan yet to be seen. A brief lull had taken hold of the countryside. The early summer threshing was long over. The grapes had their first color on the greener hillsides.

So all was quiet for tomorrow’s battle. For all the summer heat, his Boiotia was not nearly as dry, not so barren as he feared it might be. Towering Mt. Parnassos was at his rear. A peak higher than Helikon, with a touch of the undying snow even in summer. To his left rose rocky Ptôon by the sea. Up there was the temple of Apollo. He had hiked the pathway with Malgis—even after his father had stopped seeing the older Olympian gods, and had turned instead toward worship of the Pythagoreans, whose god was Lord Logos, and whose priests were philosophers, claiming that the divine was not just more powerful than men, but more moral as well. On behalf of this god, long ago his father Malgis had died at the battle at Koroneia. For all this land, long ago Mêlon had ruined his leg against the Spartans. And for all the Boiotians, his only son, the best of the three of the Malgidai, was tomorrow willing to ride into the spears of the Spartan horse.

As he scanned the plains and hills around Leuktra, Mêlon saw now how the farmer creates his own better world of trees and vines. He gets lost in it, and needs someone to bring him out of his refuge. His son had now done that for him and so brought him to the grand vision of Epaminondas, but then, again, Lophis had never fought the Spartans. Any who did, as Mêlon had, might wish to never again, and so would remember why the world of the orchard and vineyard was far safer than the chaos of what men produce in town. Yet then again, no man can be the good citizen alone on his ground, although Mêlon had tried that for thirty years and more, in between his service for the Boiotians. A farm may hide failure, be a salve to hurt and sorrow, even disguise fear and timidity, but it cannot be a barricade of peace when there is mayhem outside its walls. And there was now plenty of that at Leuktra.

As he neared the creek of Leuktra, Mêlon saw again from the jostling wagon that his Boiotia was a holy place. It was no pigsty of marshes and dullards the way the Spartans slandered it. If it were, why would they be here this day to take it? It was time anyway for this settling up tomorrow, Mêlon thought, even if it meant that the Malgidai would have to mortgage their all—himself, Chiôn, Gorgos, and Lophis, maybe even the farm itself. The fight was not yet about Epaminondas freeing the slaves of the south, he assured himself. Not entirely tomorrow. Nor about the Pythagorean dream of “we’re all equal” that would take the gods to enforce. Nor about the promises of oracles and seers that Mêlon was the apple who had to fight at Leuktra for Epaminondas to win—and for a Spartan king to die.

Apart from all that, Mêlon and his son Lophis would battle just this once more to push the invaders off his soil. Or at least he thought he would, since he had not yet met this Epaminondas—this huge jar into which everyone seems to throw their dreams, fears, and hopes. The seers said the men of his age were not like the grandfathers of their grandfathers, who had saved the Hellenes from the Persians at Marathon. Mêlon’s debased generation was said not even to have been the equal of their grandfathers, who had helped the Spartans stop Athens from gobbling down Hellas. But now the Boiotians—right here, tomorrow—they could at least end Sparta? That would prove that the polis was not through yet, that the blood of the old heroes of Hellas, of Miltiades, of Lysander and of Pagondas, still ran in the veins of the Boiotian farmers at Leuktra.

So a sense of contentment, of

eudaimonia

had come over Mêlon, son of Malgis, as they had left his farm this past morning. For its vines and trees, and tall grass—and for fear of being found wanting in the eyes of the dead—he would pick up his spear. For his son Lophis, and his son’s young wife Damô and their boys and their neighbor Staphis who had braved the hoots of the Thespians in the assembly—and for the simple folk of his Thespiai who never had harmed Sparta—he would fight Sparta and seek to end Sparta. Staphis with the smelly single cloak and a bleary eye and his stick arms was the least likely hoplite in Thespiai—and the only one who had joined the Malgidai for battle. Even now Mêlon recalled the rabble in the assembly back home, who had hooted the vine man Staphis down when he alone had called for the town to muster with Epaminondas.

“We know,” Staphis had screamed back at them, “that the Pythagoreans will join Epaminondas, whoever this general is.” Vine growers rarely had the ear of the assembly and he was not about to lose his moment as he bellowed out more. “And we know his fellow Thebans will as well. And those who could use plunder from the dead on the battlefield may wish to go to Leuktra. Others who hate Sparta will line up in the front rank. But why should we farmers on the high ground of Helikon care whether these Spartan invaders torched the wheat land of the lowlanders below or trample our vines? Why would I, with two daughters and a gout-footed wife, risk a spear in my gut, when my grapes are overripe and rot on the vine for want of pickers? Why? Well, I will tell you: for the name of Helikon, of course. And for the pride of our Thespiai, and for holy Boiotia that bore and raised us. Yes, for the idea that no Spartan will ever again barge into the ground of their betters, and that on the morrow, we shall end Sparta for good as we knew it. For all that, I, Staphis, will walk alone to find a slot in the front line of my general Epaminondas.”

Now remembering all the lofty words of the defiant Staphis, as he neared the enemy encamped at Leuktra, Mêlon sensed, like Staphis, that decay was not fated. Decline was a choice, a wish even, to idle and to lounge and willingly to become lesser folk, rust that appeared to feed on the hard iron of what their parents had wrought. If Boiotia were to fall, it would not be because of Lichas and his Spartans, or Persians from across the sea, or the wild tribes who swept from Makedon, but because lesser Boiotians simply let them in, preferring wine and flute-girls to blood and iron.

The farmers of Helikon had the good on their side. They had never yet marched down into Lakonia to bother the Spartans. Mêlon had never sung war songs like the war-loving Spartans did. But now, today, they were burning his homeland of Boiotia, and nearing his polis Thespiai. Until now, for much of his life, he certainly had not had much feeling one way or another about their helot slaves—at least not until this summer. But the Spartans had provoked Epaminondas, and now the general in fury would risk thousands of Boiotian farmers killed for the freedom of the Messenian serfs and to end Sparta for good. Is that the nemesis that the hubris of Sparta has earned—and their ruin that was to come at last? But was there another way to stop them? Surely not, at least not for good. A wall of stone, a mountain perhaps could block a line of advancing Spartan hoplites, but not other mere men, at least as he had known them until now. A man, Mêlon now smiled at his wild thoughts, could think of a lot as he rested in the back of a cart on the way to war.

Each spring, the tall men of Sparta from the south came to torch when the grain of Boiotia grew heavy and dry. This summer, almost on a town crier’s schedule, King Agesilaos had ordered the other king, his royal partner, Kleombrotos, to bring in another army. The two promised that Boiotia would be theirs before the rumors of war and promises of revolution spread to the south and took flesh—before the rest of Hellas got drunk, they also said, on the mad idea that the poor man with nothing could vote in the assembly right alongside the noble with everything and put the worse in charge of the better. All that would ruin what was once good in Hellas. Or so they also said.

Boiotia knew that Kleombrotos, if his army won at Leuktra tomorrow, would then unleash his henchman Lichas to kill the Pythagoreans of Thebes. Lichas would round them all up, since their talk about equality was at the root of this democracy—and their notion that their one god judged men on their merit rather than, like the Olympians, by their power and nobility. The Spartans warred not just against the Boiotians, but against the notion of democracy itself.

Mêlon knew Epaminondas was right to face the Spartans down, even though he did not believe he was fated to kill a Spartan king or that any such silly prophecy was needed in the ranks to win. He was here instead to do some big thing. He would accomplish something different from the last years, to end his quiet and plunge into the roaring storm’s surf rather than hear it crash from a safe distance. Perhaps the muscles of his Chiôn and his own skill with the spear would put an end to it all. Who better than these two veterans could stop the Spartans? Tomorrow was as good a day as any to start, here at this fight beside Leuktra creek.

Then a strong breeze blew across his face from the south, and Melôn was back out of his dreams of the day and fully awake again, once again the lame farmer from Helikon and no longer the would-be savior of Hellas. The wagon had pulled up well beyond the outer edge of the Theban camps, almost alone on the upland plateau. A thousand tents spread down the slopes to the gully at Leuktra. The “white” creek of Leuktra was mostly a trickle by summer, more fouled and black with moss than white with running foam. Finally the three neared the flat top of the hillock most distant from the center of the Theban camp. Some oaks and a laurel tree there shaded a small spring that fed a clean stony pool. Only a few Theban tents were this far up, across the way on the neighboring rise above their army below.

Gorgos was still singing his most peculiar Spartan tune—“It is a noble thing for a good man to die, falling among the front-fighters, fighting on behalf of his fatherland.” The harsh beat sounded like some nonsense from an ancient Spartan war song of the poet Tyrtaios—even though the three in the wagon were supposed to be Boiotians, pledged to fight for General Epaminondas, the final arrivals from Mt. Helikon to the Boiotian camp.

Gorgos had kept on with his song even as the wagon passed by the Boiotian campfires—all the louder, the more numerous the enemy tents appeared on the hills across the gully. In his defense, he often claimed that before the Malgidai had captured him he too had been a helot, a noble of Messenia born far to the south, but one Spartan freed and Spartan trained. Now with seventy summers and maybe more behind him, his gravelly voice kept croaking out Doric song lines like, “fighting on behalf of his fatherland.” But whose fatherland did he mean?

The closer the wagon had come to the army of the Boiotians, the wilder the mind of Gorgos became. He decided now that he did not like at all this idea of fighting against his old benefactors, the Spartans. Not even if they were here up north tramping on his master’s ground and he had not been with them for more than twenty years. Only with the threat of the lash had Mêlon dragged him with armor to the stream here at Leuktra. And Gorgos suspected that these Boiotian pigs were not fighting tomorrow just as defenders against the Spartans’ invasion, at least not entirely, or even that this bloodletting would be the end of it. Instead if they won tomorrow, if they beat their betters, they would promise endless battles to come in the south for Epaminondas. He was their ragged dreamer who got them drunk on notions that they were going to be liberators and freers of chattel slaves and so become better even than the slave-owning gods on Olympos themselves—notions far more dangerous than fighting for mere plunder, pride, or revenge. Could not a brave man kill that faker, slit his throat, cleave off his head—and so save untold men from dying tomorrow?