The Eternal Flame (35 page)

Authors: Greg Egan

Tags: #Science Fiction, #General, #Space Opera, #Fiction

“The end result depends on the order,” Patrizia concluded. “Since you can’t reverse the order when you multiply two vectors together, that’s always going to show up here and spoil things.”

She was right. There were other choices besides Romolo’s for the square root of minus one, but they all had similar problems. You could multiply on the left or on the right by Up or Down, East or West, North or South; they would all produce quarter turns in two distinct planes. But in every single case, you could find a rotation that wrecked the scheme.

Romolo took the defeat with good humor. “Two plus two equals four, but all nature cares about is non-commutative multiplication.”

Patrizia smoothed the calculations off her chest, but Carla could see her turning something over in her mind. “What if the luxagen wave follows a different rule?” she suggested. “It’s still a pair of complex numbers, and you can still join them together to make something four-dimensional—but when you rotate the luxagen, that four-dimensional object doesn’t change the way a vector does.”

“What law would it follow, then?” Carla asked.

“Suppose we choose

right

-multiplication by Up as the square root of minus one,” Patrizia replied. “Then multiplying on the

left

will always commute with that: it makes no difference which one you do first.”

“Sure,” Carla agreed. “But what’s your law of rotation?”

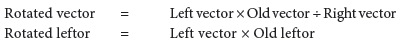

“Multiplying on the left, nothing more,” Patrizia said. “Whenever an ordinary vector gets rotated by being multiplied on the left and divided on the right, this new thing—call it a ‘leftor’—only gets the first operation. Forget about dividing it.” She scrawled two equations on her chest:

Carla was uneasy. “So you only use half the description of the rotation? The rest is thrown away?”

“Why not?” Patrizia challenged her. “Doesn’t it leave you free to multiply on the right—letting the square root of minus one commute with the rotation?”

“Yes, but that’s not the only thing that has to work!” Carla could hear the impatience in her voice; she forced herself to be calm. She was ravenous, and she was late to meet Carlo—but she couldn’t eat until morning anyway, and if she cut this short now she’d only resent it.

“What else has to work?” Romolo asked.

Carla thought for a while. “Suppose you perform two rotations in succession,” she said. “Patrizia’s rule tells you how this new kind of object changes with each rotation. But then, what if you combine the two rotations into a single operation—one rotation with the same overall effect. Do the rules still match up, every step of the way?”

Patrizia said, “However many rotations you perform, you just end up multiplying all of their left vectors together. Whether it’s for a vector or a leftor, you’re combining them in exactly the same way!”

That argument sounded impeccable, but Carla still couldn’t accept it; throwing out the right vector had to have

some

effect. “Ah. What if you do two half-turns in the same plane?”

“You get a full turn, of course,” Patrizia replied. “Which has no effect at all.”

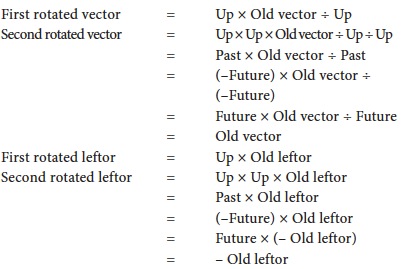

“But not from your rule!” Carla wrote the equations for each step, obtaining a half-turn in the North-East plane by multiplying on the left by Up and dividing by Up on the right.

Patrizia kept rereading the calculation, as if hoping she might spot some flaw in it. Finally she said, “You’re right—but it makes no difference. Didn’t you tell us a lapse or two ago that rotating a luxagen wave in the complex plane has no effect on the physics?”

“Yes.” Carla looked down at her final result again. Two half-turns left a vector unchanged; two half-turns left a leftor multiplied by minus one. But the probabilities that could be extracted from a luxagen wave involved

the square of the absolute value

of some component of the wave. Multiplying the entire wave by minus one wouldn’t change any of those probabilities.

Romolo said, “So when you rotate this system all the way back to its starting point, the wave changes sign. But we can’t actually measure that… so it doesn’t matter?”

“It’s strange,” Carla agreed. “But what troubles me more is treating the rotation’s left vector differently from the right. All it takes to swap the role of those two vectors is to view the system in a mirror. Should physics look different, viewed in a mirror? Have we seen any evidence of that?”

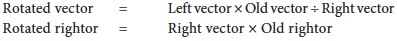

Patrizia took the criticism seriously. “What if we tried to balance it, then? Could we throw in a ‘rightor’ as well as a leftor, for symmetry’s sake?” She wrote the transformation rule for this new geometrical object, a mirror image of her previous invention.

“Throw it in where?” Romolo asked.

“Into the luxagen wave,” Patrizia replied. “Two more complex numbers, but these ones transform by the rightor rule. If you look at the system in a mirror, the leftor and rightor change places.”

“That sounds very elegant,” Romolo said, “but haven’t you just doubled the number of polarizations from two to four?”

“Hmm.” Patrizia grimaced. “That would defeat the whole point.”

Carla pondered the new proposal. “The light field is a four-dimensional vector—but we don’t get four polarizations, because of the relationship between the field vector and the energy-momentum vector. What if there’s a relationship between the luxagen field—the leftor and the rightor—and the luxagen’s energy-momentum vector? Something that brings the number of polarizations back down to two.”

Romolo said, “What kind of relationship? Setting a leftor or a rightor perpendicular to an ordinary vector won’t work—when you rotate all three of them, they’ll change in different ways, so the relationship won’t be maintained.”

“That’s true,” Patrizia conceded. She drove her fist into her gut; the glorious distraction was losing its power again. “Maybe we should tear this up and start again.”

Carla said, “No. The relationship’s simple.”

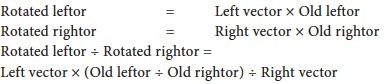

She wrote:

“That’s it,” she said. “Just look at how these three things transform when we rotate them.”

“A leftor divided by a rightor changes in exactly the same way as an ordinary vector. So if we demand that the energy-momentum vector of a luxagen wave is proportional to the wave’s leftor divided by its rightor, rotation won’t break the relationship—and any free luxagen wave that meets this condition could be rotated into agreement with any other.”

Romolo said, “And the rightor is completely fixed by the leftor and the energy-momentum vector. There are no extra polarizations.”

Patrizia looked dazed. She said, “Follow the geometry and everything falls into place.” She exchanged a glance with Carla; this was not the first time they’d seen it happen, but the sheer power of the approach was indisputable now. “Two polarizations, to fit the Rule of Two. But what do they mean, physically?”

Carla said, “Let’s work with a stationary luxagen, to keep things simple. Then its energy-momentum vector points straight into our future. Suppose the luxagen field has a leftor of Up; its rightor will be the same, because Up divided by Up is Future.

“Suppose we rotate this luxagen in the horizontal plane: the North-East plane. Any such rotation will come from multiplying on the left and dividing on the right by a vector in the Future-Up plane—which will move our leftor and rightor from Up to some new position in the Future-Up plane. But the Future-Up plane is one we’re treating as a single complex number, so if the luxagen field

remains

within that plane, it hasn’t really undergone any physical change. And if you can rotate a luxagen in the horizontal plane without changing it, it must be vertically polarized.”

“So how do the same rotations affect the other polarization?” Patrizia wondered. “Pick any leftor in the other complex plane: the North-East plane. Say we choose North. If you multiply North on the left by a vector in the Future-Up plane, the result still lies in the North-East plane. So again, rotating the luxagen in the horizontal plane won’t change anything.”

“

Two

vertical polarizations?” Romolo hummed softly in confusion, but then he tried to work through the contradiction. “It’s meaningless to talk about two vertical polarizations of light—‘up’ as opposed to ‘down’—because the wave changes sign as it oscillates; if the light field points up at one instant it will point down a moment later. But when a

leftor

is multiplied by a complex number that oscillates over time, that oscillation will never move it from one complex plane to the other. So these two vertical polarizations really are separate possibilities.”