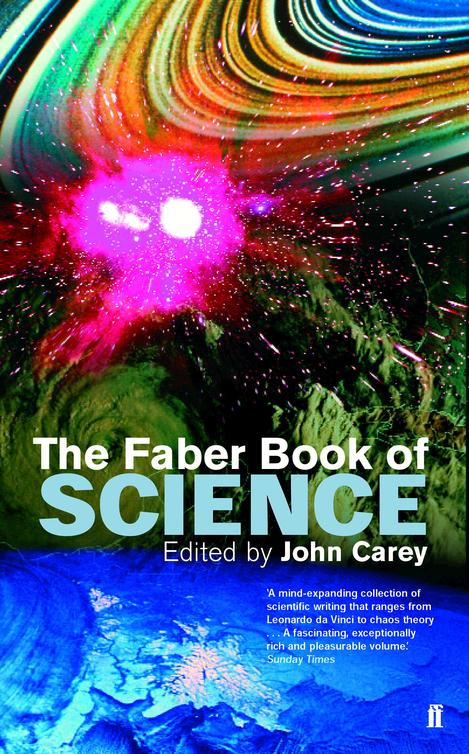

The Faber Book of Science

Read The Faber Book of Science Online

Authors: John Carey

Further acclaim for

The

Faber

Book

of

Science:

‘As a book to pick up and dip into from time to time, this will be a compelling volume to artists and scientists alike.’

New

Scientist

‘Professor Carey’s anthology had me gripped … The fruit of wide reading and impressive understanding.’

Sunday

Telegraph

‘This is a delightful, enchanting book – the erudition of ages garlanded by Carey’s dry wit and infectious enthusiasm.’

Mail

on

Sunday

‘A series of fascinating essays in such diverse subjects as malaria, the first electric light bulbs, early photographs and Charles Lyell’s shocking revelations on the shifting of rocks. A must for all those, like me, who long to be educated, and fast.’ Beryl Bainbridge, Books of the Year,

Independent

‘A big, beautiful, desirable book, including marvels like Ruskin in praise of the “russet velvet” of rust, or Nabokov waiting among the darkening lilacs to spot the “vibrational halo” of “an olive and pink Hummingbird moth”.’

Daily

Telegraph

Science

edited by

JOHN CAREY

Prelude: The Misfit from Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci

Going inside the Body

Andreas Vesalius

Galileo and the Telescope

Galileo Galilei

William Harvey and the Witches

Geoffrey Keynes

The Hunting Spider

Robert Hooke and John Evelyn

Early Blood Transfusion

Henry Oldenburg and Thomas Shadwell

Little Animals in Water

Antony van Leeuwenhoek

An Apple and Colours

Sir Isaac Newton and others

The Little Red Mouse and the Field Cricket

Gilbert White

Two Mice Discover Oxygen

Joseph Priestley

Discovering Uranus

Alfred Noyes

The Big Bang and Vegetable Love

Erasmus Darwin

Taming the Speckled Monster

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Edward Jenner

The Menace of Population

Thomas Malthus

How the Giraffe Got its Neck

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

,

George Bernard Shaw and Richard Wilbur

Medical Studies, Paris 1821

Hector Berlioz

The Man with a Lid on his Stomach

William Beaumont

Those Dreadful Hammers: Lyell and the New Geology

Charles Lyell

The Discovery of Worrying

Adam Phillips

Pictures for the Million

Samuel F. B. Morse and Marc Antoine Gaudin

The Battle of the Ants

Henry David Thoreau

Submarine Gardens of Eden: Devon, 1858–9

Edmund Gosse

The Devil’s Chaplain

Charles Darwin

The Discovery of Prehistory

Daniel J. Boorstin

Chains and Rings: Kekule’s Dreams

August Kekule

On a Piece of Chalk

T. H.Huxley

Siberia Breeds a Prophet

Bernard Jaffe

Socialism and Bacteria

David Bodanis

God and Molecules

James Clerk Maxwell

Inventing Electric Light

Francis Jehl

Bird’s Custard: The True Story

Nicholas Kurti

Birth Control: The Diaphragm

Angus McLaren

Headless Sex: The Praying Mantis

L. O. Howard

The World as Sculpture

William James

The Discovery of X-Rays

Wilhelm Roentgen, H.J.W. Dam, and others

No Sun in Paris

Henri Becquerel

The Innocence of Radium

Lavinia Greenlaw

The Secret of the Mosquito’s Stomach

Ronald Ross

The Poet and the Scientist

Hugh MacDiarmid

Wasps, Moths and Fossils

Jean-Henri Fabre

The Massacre of the Males

Maurice Maeterlinck

Freud on Perversion

Sigmund Freud and W. H. Auden

A Cuckoo in a Robin’s Nest

W. H. Hudson

Was the World Made for Man?

Mark Twain

Drawing the Nerves

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Discovering the Nucleus

C. P. Snow

Death of a Naturalist

W. N. P. Barbellion

Relating Relativity

Albert Einstein, Bertrand Russell,

A. S. Eddington and others

Uncertainty and Other Worlds

F. W. Bridgman and others

Quantum Mechanics: Mines and Machine-Guns

Max Born

Why Light Travels in Straight Lines

Peter Atkins

Telling the Workers about Science

J. B. S. Haldane

The Making of the Eye

Sir Charles Sherrington

Green Mould in the Wind

Sarah R. Reidman and Elton T. Gustafson

In the Black Squash Court:

The First Atomic Pile

Laura Fermi

A Death and the Bomb

Richard Feynman

The Story of a Carbon Atom

Primo Levi

The Hot, Mobile Earth

Charles Officer and Jake Page

The Poet and the Surgeon

James Kirkup and Dannie Abse

Enter Love and Enter Death

Joseph Wood Krutch

In the Primeval Swamp

Jacquetta Hawkes

Krakatau: The Aftermath

Edward O. Wilson

Russian Butterflies

Vladimir Nabokov

Discovering a Medieval Louse

John Steinbeck

The Gecko’s Belly

Italo Calvino

On The Moon

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin

Otto Frisch Explains Atomic Particles

Otto Frisch, Murray Gell-Mann and John Updike

From Stardust to Flesh

Nigel Calder and Ted Hughes

The Fall-Out Planet

J. E Lovelock

Galactic Diary of an Edwardian Lady

Edward Larrissy

The Light of Common Day

Arthur C. Clarke

Can We Know the Universe? Reflections on a Grain of Salt

Carl Sagan

On Not Discovering

Ruth Benedict

Negative Predictions

Sir Peter Medawar

Great Fakes of Science

Martin Gardner

Rags, Dolls and Teddy Bears

D. W. Winnicott

The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat

Oliver Sacks

Seeing the Atoms in Crystals

Lewis Wolpert and Dorothy Hodgkin

The Plan of Living Things

Francis Crick

Willow Seeds and the

Encyclopaedia

Britannica

Richard Dawkins

The Greenhouse Effect: An Alternative View

Freeman Dyson

Fractals, Chaos and Strange Attractors

Caroline Series and Paul Davies,

Tom Stoppard and Robert May

The Language of the Genes

Steve Jones

The aim of this book is to make science intelligible to non-scientists. Of course, like any anthology, it is meant to be entertaining, intriguing, lendable-to-friends and good-to-read as well, and the first question I asked about any piece I thought of including was, Is this so well written that I want to read it twice? If the answer was no, it was instantly scrapped. But alongside this question I asked, Does this supply, as it goes along, the scientific knowledge you need to understand it? Will it be clear to someone who is not mathematical, and has no extensive scientific education? Even if it was admirable in other ways, failure to qualify on these counts landed it on the reject pile.

Scientists themselves are not always good at judging intelligibility – and why should they be? They are specialists, paid to communicate with fellow specialists. Of course, they have to communicate, too, with industry, the government, grant-giving bodies and other institutions. But they can often assume a level of expertise in these negotiations which is well above that of the general public. Over the last five years I have read many books and articles by scientists, ostensibly for a popular readership, which start out intelligibly and fairly soon hit a quagmire of equations or a thicket of fuse-blowing technicalities, from which no non-scientist could emerge intact.

Relativity:

The

Special

and

General

Theory.

A

Popular

Exposition,

by Albert Einstein, Ph.D. (1920) is only a particularly distinguished example of a class of ‘popular expositions’, still being published, that could not conceivably be understood by more than a tiny fraction of any populace.

Fortunately for this anthology, however, popular science has improved immensely in the later twentieth century. Writers like Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Martin Gardner, Freeman Dyson, Carl Sagan, Richard Feynman, Stephen Jay Gould, Peter Medawar, Stephen Hawking, Lewis Wolpert and Richard Dawkins have transformed the genre, combining expert knowledge with an urge to be understood,

and bridging the intelligibility gap to delight and instruct huge readerships. In the process, they have created a new kind of late twentieth-century literature, which demands to be recognized as a separate genre, distinct from the old literary forms, and conveying pleasures and triumphs quite distinct from theirs.

True, these writers had predecessors in the nineteenth century – T. H. Huxley, for example, or Charles Darwin himself, who also strove to reach the general reading public. But in the mid-nineteenth century the general reading public was a much smaller and more select thing than it is now. The challenge for a late twentieth-century writer of popular science is different and greater. The books that succeed represent achievements of a remarkable and unprecedented kind. Nor is it clear on what grounds they can be reckoned inferior to novels, poems and other representatives of the older genres. In what respect, for example, is a masterpiece like Richard Dawkins’s

The

Blind

Watchmaker

imaginatively inferior to a distinguished work of fiction such as Martin Amis’s

Einstein’s

Monsters

(or the hundreds of lesser novels that jam the publishers’ lists each year)? Both are clearly the products of brilliant minds; both are highly imaginative; and Amis is more excited by scientific ideas than most contemporary writers. Nevertheless, the essential distinction between them seems to be that between knowledge and ignorance. From the viewpoint of late twentieth-century thought, Dawkins’s book represents the instructed and Amis’s the uninstructed imagination.

Because I wanted the pieces I included to be seriously informative as well as enjoyable, I decided not to allow in science fiction (which would, in any case, need an anthology of its own), or those plentiful anecdotes about scientists’ private lives which show how droll or winning they were despite their erudition. The misty precursors of true science – alchemy, astrology – have also been left out, partly because they can now be classified as history not science, and partly because they tend to encourage in the reader an amused and superior response which is not the reaction I am looking for.

For similar reasons I decided, after some hesitation, not to include ancient science (Aristotle, Pliny, etc.). It is true, of course, that this sometimes foreshadows modern science. But even when it does it is often forbiddingly technical, in a way that no amount of jazzing-up in translation can overcome. After a good deal of searching, I concluded that there were virtually no examples of ancient science that would

have anything more than curiosity value – if that – for a general reader today. So my anthology starts with the Renaissance, at a point where two sciences, anatomy and astronomy, take decisive steps towards the modern age, and find exponents who can still be read with pleasure.

A final kind of writing I decided (rather quickly) to exclude was the large body of opinionativeness that has gathered around such questions as whether science is a Good or a Bad Thing, and whether we would be better off if we did not know the earth went round the sun. Ignorance and prejudice seem to be the most prolific contributors to this branch of controversy, and I am not anxious to give either house-room.

In the main, then, I have tried to stick to serious science, though serious science softened up for general consumption. Scientists will object quite rightly that I have included technology as well as science. The pieces on the Wright brothers’ aeroplane or on Daguerre and the first photograph, for example, would not figure in a strictly scientific anthology. But I included them and others because, for the general reader, science and technology are intimately connected – as, indeed, they are for scientists. Photography and manned flight both became possible because of scientific perceptions, and technology has advanced scientific discovery from the time of Galileo’s telescope.

Choosing the passages to include was one thing: arranging them, another. Should I separate out the various sciences – all the biology pieces in one section; all the chemistry in another? Or would a roughly chronological arrangement be better? I decided it would, because jumping from science to science with each item makes for a livelier read, and the chronological framework turns the book into a story – a way of taking in the development of science over the last five centuries. Some of this story-telling is carried on in the introductions to each extract, and sometimes – as, for example, in the sections on Relativity

and the Uncertainty Principle – I have drawn together material from several sources, including poets and novelists, to show how a particular scientific discovery did, or did not, enter the

bloodstream

of the culture.

Broadly speaking science-writing tends towards one of two modes, the mind-stretching and the explanatory. In practice, of course, any particular piece of science-writing will combine the two in various proportions. Still, they seem to be the extremes between which

science-writing

happens. The mind-stretching, also called the gee-whizz mode,

aims to arouse wonder, and corresponds to the Sublime in traditional literary categories. When scientists tell us that if we could place in a row all the capillaries in a single human body they would reach across the Atlantic, or that the average man has 25 billion red blood corpuscles, or that the number of nerve cells in the cerebral cortex of the brain is twice the population of the globe, these are contributions to the mind-stretching mode – which does not mean, of course, that they are not serious and profound in their implications as well. A similarly amazing example, and less flattering to our self-esteem, is the proposition (from an essay by George Wald) that though a planet of the earth’s size and temperature is a comparatively rare event in the universe, it is estimated that at least 100,000 planets like the earth exist in our galaxy alone, and since some 100 million galaxies lie within the range of our most powerful telescopes, it follows that throughout observable space we can count on the existence of at least 10 million million planets more or less like ours.

As readers will find, I have included some examples of this mode in my anthology, because the peculiar thrill and spiritual charge of science would not be fairly represented without it. But my preference has been, and is, for the other mode, the explanatory. What I most value in-science-writing is the feeling of enlightenment that comes with a piece of evidence being correctly interpreted, or a problem being ingeniously solved, or a scientific principle being exposed and clarified. There are many instances of these three processes in the anthology, but if I had to choose one favourite example of each they would be from Galileo, Darwin and Haldane respectively.

When Galileo looked at the moon through his telescope, he and everyone else thought it was a perfect sphere. He was astonished, he tells us, to see bright points within its darkened part, which gradually increased in size and brightness till they joined up with its bright part. It occurred to him that they were just like mountain tops on earth, which are touched by the sun’s morning rays while the lower ground is still in shadow. So he deduced correctly that the moon’s surface was not smooth after all, but mountainous. To follow Galileo as he explains his observations step by step is to share an experience of scientific enlightenment that fiction and poetry, for all their powers, cannot give, since they can never be so authentically engaged with actuality and discovery.

Darwin supplies a beautiful example of the second process, the

ingenious solution of a problem, when he is faced with the need to explain how species of freshwater plants could spread to remote oceanic islands without being separately created by God. It occurs to him that the seeds might be carried on the muddy feet of wading birds that frequent the edges of ponds. But that raises the question of whether pond mud contains seeds in sufficient quantities. So he takes three tablespoonfuls of mud from the edge of his pond in February – enough to fill a breakfast cup – and keeps it covered in his study for six months, pulling up and counting each plant as it grows. Five hundred and thirty-seven plants grow, of many different species, so that Darwin is able to conclude that it would be an ‘inexplicable circumstance’ if wading birds did not transport the seeds of freshwater plants, as he had suspected. Once again, fiction could not compete with the impact of this, since the force of Darwin’s account depends precisely on its not being fiction but fact.

J. B. S. Haldane’s famous essay ‘On Being the Right Size’ superbly exemplifies the third process – the exposition of a scientific principle. Restricting his mathematics to simple arithmetic, and keeping in mind the need for powerful, graphic examples, Haldane is able to demonstrate, unforgettably, by the end of his second paragraph, that the 60-foot-high Giants Pope and Pagan in Bunyan’s

Pilgrim’s

Progress

could never have existed, because they would have broken their thighs every time they walked. The example is, of course, purposefully chosen, for out goes, with Bunyan, the whole world of (as Haldane saw it) religious mumbo-jumbo that Bunyan stood for, and the light of pure reason comes flooding in instead.

But if the explanatory mode is science-writing’s breath of life – its armoury, palette and climate – the problem for science-writers is how to explain. How can science be made intelligible to non-scientists? The least hopeful answer is that it cannot. Giving an inkling of what modern science means to readers who cannot manage higher mathematics is, Richard Feynman has proposed, like explaining music to the deaf. This would be a desolating conclusion if Feynman were not himself among the most brilliant of explainers. His success depends upon his genius for making his material human. He saturates his writing with his individual style and personality. But, more than that, he freely imports a kind of animism into his experimental accounts – discussing, for example, how an individual photon ‘makes up its mind’ which of a number of possible paths to follow.

Ruskin uses animism, too, when – in his masterly tribute to rust – he tells his readers that iron ‘breathes’, and ‘takes oxygen from the atmosphere as eagerly as we do’. Miroslav Holub is animistic when (in perhaps the most mind-expanding piece in the whole anthology) he imagines the adrenalin and the stress hormones in the spilt blood of a dead muskrat still sending out their alarms, and the white blood cells still busily trying to perform their accustomed tasks, bewildered by the unusual temperature outside the muskrat’s body. In fact, Feynman-Ruskin-Holub-type animism is a persistent ally in the popular science-writer’s struggle to engage the reader’s understanding.

To a scientist, this might seem ridiculous. Lewis Carroll rubbished the whole idea in

The

Dynamics

of

a

Particle:

It was a lovely Autumn evening, and the glorious effects of chromatic aberration were beginning to show themselves in the atmosphere as the earth revolved away from the great western luminary, when two lines might have been observed wending their weary way across a plane superficies. The elder of the two had by long practice acquired the art, so painful to young and impulsive loci, of lying evenly between his extreme points; but the younger, in her girlish impetuosity, was ever longing to diverge and become a hyperbola or some such romantic and boundless curve …

However, it is not clear that animism is as daft as Carroll makes it appear. All science is inevitably drenched in our human presumptions, designs and conceptions. We cannot get outside the human shapes of our brains. Our observation inevitably alters what it observes. This perception is usually associated with Heisenberg. But it was already evident to Francis Bacon at the start of the seventeenth century, who saw that perfect, pure objective science was impossible, not only because we are forced to use language, or some kind of numerical notation, which does not ‘naturally’ belong to the objects we name or number, but also because we seek patterns, shapes and symmetries in nature which correspond to our own preconceptions, not to anything that is ‘really’ there. From this viewpoint, to say that iron ‘breathes’ is no more absurd than to say that it is called ‘iron’, or that its chemical symbol is Fe. In each case, we add something human to its remote, alien, unknowable nature – a nature that has nothing to do with human thought, and is therefore altered the instant we think about it.