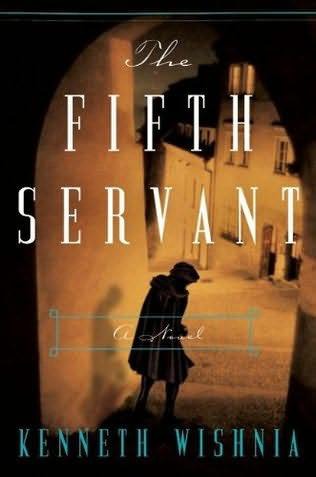

The Fifth Servant

Authors: Kenneth Wishnia

The Fifth Servant

Kenneth Wishnia

For a thousand unknown ancestors

whose names have come down to us as

Fink, Greenberg, Passoff, and Wishnia

shammes

—

n

[Yiddish

shames

, fr. MHeb

shammash

, fr.

Aram

shemmash

to serve]

1

: the sexton of a synagogue

shamus

—

n

[prob. fr. Yiddish

shames;

prob. fr. a jocular comparison of the duties of a sexton and those of a store detective] (1929)

1

slang:

policeman

2

slang:

a private detective

—

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary

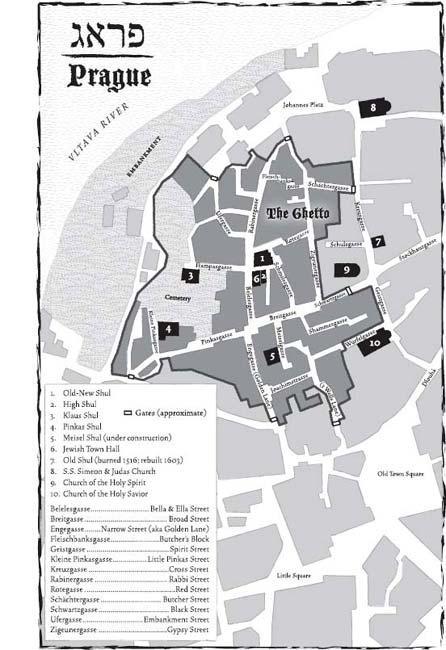

Map

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ONE OF THE MANY PROBLEMS facing me as I wrote this book was how to present the dialogue, which represents conversations in Yiddish, Czech, and German.

I found the answer while reading a Yiddish translation of the Book of Jonah. You know the story: God calls on Jonah to tell the people of

Nineveh

to stop their wickedness, but Jonah flees from his duty to God and boards a ship. God raises a storm, and all the sailors start praying to their various gods and tossing cargo overboard, but the storm doesn’t subside. Then the ship’s captain discovers Jonah asleep in the hold. At this portentous moment, instead of giving a high-minded warning about the wrath of God, the captain says,

“Vos iz mit dir?”

I couldn’t help laughing when I read that passage because it seemed like an incongruously informal statement under the circumstances—literally, “What’s with you?” So I checked with Professor Robert Hoberman, a linguist at SUNY Stony Brook, who confirmed that the phrase in the original Hebrew was quite common, colloquial, and very modern sounding.

That served as my guiding principle: the idea that these late sixteenth-century people were speaking a language that sounded perfectly ordinary to them, although I still needed to find a compromise between the excessively archaic and the jarringly modern. (And if some readers feel that phrases such as “Somebody must have blabbed” sound too modern, I would point out that Chaucer used

blabbe

in the 1370s. Other examples include “protection” money in several sixteenth-century sources, legal “cases” from the fourteenth century, and “witness,” which dates to the tenth century.)

This solution can also be found in contemporary foreign-language translations of Shakespeare, which deal with the same problem by modernizing obscure, archaic, and obsolete words in the source language (Elizabethan English), rather than by supplying an equally obscure word in the target language, such as an “equivalent” medieval French word in a modern French translation.

So there you have it. If I can cite translations of the Bible and Shakespeare as supporting examples, what more do you want from me? Now

geyt gezunterheyt

. Translation: enjoy.

—K.W.

I form the light, and create darkness:

I make peace, and create evil:

I, the Lord, do all these things.

—ISAIAH 45:7

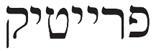

Freitag

Pátek

Friday

CHAPTER 1

A DISTANT CRY WOKE ME.

I sat up and looked out the attic window over the sloping rooftops on the north side of

Broad Street

, which the German-speaking Jews called the Breitgasse. It was too early to see the horizon. The city and sky were an inseparable mass of darkness, and the scream’s dying echoes evaporated into the air, like the breath I could see coming out of my mouth.

I was in bed with two strange men—the

mikveh

attendant and the street cleaner—and the room was damn near freezing. It was spring by the calendar, but it was still winter at heart, and I could feel in my bones that it was going to rain, like it did every year on the Christian holiday of Good Friday. I’d have bet five gold pieces on it, but there weren’t any takers, and I didn’t have five gold pieces. If you turned out my pockets, all you’d get for your troubles would be a few lonely coppers and some mighty fine lint imported all the way from the

Kingdom

of

Poland

.

But something had jarred me awake. Like it says in the

Megillas Esther

, the king found no rest, so I listened intently, the fog of sleep still swirling around in my head.

Muffled and ghostly, a distant cry floated over the narrow streets of the Jewish Town:

“Gertaaaaaah—!”

Goose bumps rose on my arms, as if the spirit of God had blown right past me and withdrawn from the room. If a Christian child was missing from its bed we were sure to be accused, and all of a sudden I was reduced to being just another Jew in a city that tolerated us, surrounded by an empire full of people who hated us.

Did I come all the way from the quiet town of

Slonim

just to get butchered by a bunch of latter-day Crusaders? And if the Jews got scattered, or worse, I might never see my wife Reyzl again.

Acosta’s shadow filled the doorway. “Hey, newcomer,

shlof gikher, me darf di betgevant

.” Sleep faster, I need the sheets, said the night watchman, his rough-edged Yiddish softened by the rolling

R

’s and open vowels of his Sephardic accent.

“Did you hear that shouting?” I asked, planting my feet on the cold floor. “Any trouble out there?”

“You just stick to your morning rounds and let the watchmen handle it, all right?”

My knees cracked as I stood up and groped around in the darkness for the pitcher and basin.

Seven people crammed into two beds. Three men in one, a family of peasants in the other, part of the yearly crush of country folk visiting the imperial city for the week from Shabbes Hagodl to Pesach. The country folk had washed their bodies for the Great Sabbath the week before, but their clothes still had the overripe tang of a barnful of animals.

The night watchman took it all in and said, “What, there wasn’t room for the goat?”

I had to cover my mouth to keep from laughing. It wasn’t good to joke around until I chased away the evil spirits that had settled on my hands during the night, and said the first prayers of the new day. Fortunately, the rabbi in Slonim had taught me how to get rid of the invisible demons by washing them off my hands in a basin of standing water.

Every year on Shabbes Hagodl, we listen to the Lord’s words to His servant Malakhi: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the Prophet before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord.” Then we watch and wait for a mysterious stranger who appears around this time of year and asks to be seated at the Seder. And woe to the family that turns the stranger away from their door! Because he just might be the herald of the Messiah himself.

Such is the faith that has guided us through so many narrow scrapes. When the Romans destroyed the temple in

Jerusalem

, we rebuilt the temple out of words and called it the Talmud—a temple of ideas that we can carry around with us wherever we go.

And so we outlasted the

Roman Empire

, and we’ll outlast this empire, too.

The watchman pulled off his boots, grabbed his share of the blanket, and was snoring by the time I faced the eastern wall and said my morning

Sh’ma

. I paid special attention to the part about teaching your children the word of God in order to prolong your days and the days of your children.

Halfway down the crooked stairs to the kitchen, I could hear Perl the rabbi’s wife issuing orders to the servants to scour the house for

khumets

, the last traces of leavened bread. So there were no oats or porridge or kasha to keep my stomach from growling, only a mugful of chicken broth and some stringy dried prunes. Hanneh the cook shouldn’t waste a piece of good meat on the new assistant shammes.

I warmed my fingers on the tin mug, while pots clattered and doors slammed all around me. Despite the noise, I overheard Avrom Khayim the old shammes telling the cook, “What do we need a fifth

shulklaper

for? Like a wagon needs a fifth wheel.”

But—wonder of wonders—Hanneh actually stood up for me and told the old man that the great Rabbi Judah Loew knew what he was doing. She had heard that the new man from Poland was a scholar and a scribe who had only been in Prague a few days, without a right of residency, when the great Rabbi Loew had seen a spark of promise in him and made him the

unter

-shammes at the Klaus Shul, the smallest of the four shuls that served the ghetto’s faithful.