The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (15 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

Murray may have had the favorable press sparked by ER’s resignation from the

DAR in mind when she asked permission to release word of the first lady’s letter to

Governor Price. Obliged to keep her advocacy out of the spotlight, ER directed Tommy to reply via telegram, “

Regret cannot give you permission to release Mrs. Roosevelt’s letter.”

· · ·

ON MURRAY

’

S SECOND TRIP

to Richmond, in December, the superintendent of the prison allowed her to visit Odell with Mother Waller. As

they made their way through the corridor to his death-row cell, Murray’s heart sank. The hostility and filth she and Mac had faced in the

Petersburg jail paled in comparison to “

the oppressiveness of his somber surroundings, the unrelieved gloom of barren walls and darkened cells, the desolate hours spent in waiting, and the terrifying nearness of the

electric chair a few yards away.”

Murray yearned to

send Waller her German shepherd,

Petie, to ease the isolation, although she knew this was out of the question.

It had been a year since Murray had

first written to Waller. She found him to be a “

short, stocky young man” with penetrating eyes, eager to see his mother and the young woman who spent every waking minute on his appeal. In the moment they had together, Murray questioned Waller about the shooting. He told her what he had always said about the incident: “

I am as sorry as I can be it all happened. I wasn’t trying to kill Mr. Davis. I was aiming to keep him from killing me.”

Waller’s “

straightforwardness,” his understandable fear of Davis, and the information Murray gleaned from field interviews persuaded her that he was guilty of

manslaughter—not premeditated murder. She would never see him again, but she would fight for a defendant’s right to a fair trial and against the

death penalty for the rest of her life.

· · ·

ENERGIZED BY THE VISIT

with Odell and the news that

Governor Price had granted a stay of execution until March 14, 1941, Murray generated a steady flow of letters to Waller. She spoke in her missives of faith and her sense of the historical moment. “

There is a greater power than our puny efforts at work here,” she wrote on January 23, 1941. “Let each day count for something. Read, study, think, write down your thoughts; keep a diary and write a little something in it every day. Remember the great apostle Paul who wrote such beautiful letters while he was in prison.… You have no time to get blue and down. You have a stake in

democracy also, and you must try to find the part you are playing in all this.”

To the first lady, Murray sent a document that combined her summary of the case, with profiles of Waller and Davis by

Murray Kempton, a young labor organizer turned journalist. This

pamphlet, which they coauthored, took its main title from Annie Waller’s testimony,

“All for Mr. Davis”: The Story of Sharecropper Odell Waller

, and it became the campaign’s primary publicity tool. After ER’s friend UNC president Frank

Graham endorsed the pamphlet by writing the preface, Murray came to regard him as an ally.

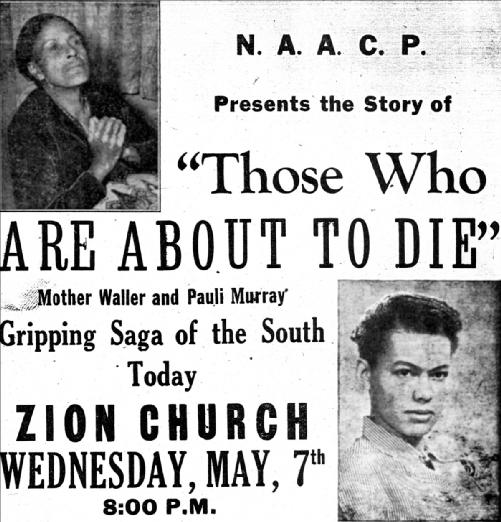

This flyer announces an appearance by Annie Waller (top) and Pauli Murray (bottom) at a fund-raiser for the Odell Waller campaign in Denver, Colorado, on May 7, 1941. During the tour, they gulped vitamins to build up “resistance against the flu.”

(Workers Defense League Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University)

11

“Might as Well Become a Lawyer”

I

n January 1941, Eleanor Roosevelt began her third term as

first lady, and the nation prepared to enter

World War II. The Waller campaign moved into high gear with Pauli Murray functioning as advance woman, press secretary, fund-raiser, and liaison between the Workers Defense League and the Waller family. Although several WDL staffers helped, only Murray was involved in every aspect of the appeal. She was encouraged—and for good reason. Waller had an outstanding legal team, plus the backing of the liberal establishment.

During the first week of the new year, Murray and Mother Waller set out on the first leg of a national tour to raise funds and public awareness.

They spoke to more than seven thousand people in twenty cities, including Boston, Chicago, Cleveland, Denver, Detroit, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh, and Washington, D.C. During the second leg, they went to Los Angeles, Portland, San Francisco, and Seattle, making stops on the way home in Cincinnati, Dayton, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Louisville, Oklahoma City, and St. Louis. They always arrived weary, having sat up all night on a train. Invariably short on money, they carried their own food and boarded with supporters.

On a typical day, Murray and Mother Waller met with members of the local media,

YMCAs,

YWCAs, unions, and

NAACP chapters; students and faculty members in high schools and colleges; religious leaders and their congregations; and liberal groups unaffiliated with the

Communist Party USA. Each presentation opened with Mother Waller’s gut-wrenching account of her son and the shooting. Murray followed with a discussion of the facts in the case and the impact of the

poll tax on the justice system in Virginia. Thirty years old and now under one hundred pounds, Murray was not much bigger than Mother Waller or much older than Odell.

But she spoke with the conviction of a veteran, often standing atop a desk or chair in practical sailor pants, drawing people of conscience to the cause.

Whenever she had a quiet moment, Murray reported back on the contacts they made, the funds raised and pledged, and the practical issues they faced. She churned out press releases and columns for the

Workers Defense Bulletin

and other outlets. She kept Odell informed about the campaign and his mother’s well-being.

She repeatedly urged him to put his story on paper in his own words.

While the tour raised $755 and the profile of the campaign, Murray returned home in an irritated state. The relentless pace had left her little time or energy for creative

writing. She had been out of college for eight years, and every job since had brought endless workdays, overwhelming responsibility, low pay, and no opportunity for advancement. Her post as field secretary for the Waller case was more of the same, except that the stakes—a young man’s life—were

greater than ever before.

An irrepressible desire to write, bone-aching fatigue, and continuing worry over

financial and family obligations put Murray in a somber mood. News of the

Nazi invasion of

Greece and

Yugoslavia, and the massive air raids against London, deepened her melancholy.

Eleanor Roosevelt takes flight with Charles “Chief” Anderson (right) at Moton Airfield, Tuskegee, Alabama, on March 31, 1941. “These boys are good pilots,” she wrote in “My Day.”

(National Archives)

· · ·

AS MURRAY CRISSCROSSED THE COUNTRY

with Mother Waller, Eleanor Roosevelt worked on refugee relief and

war preparedness. For five months, she would serve as assistant director of the

Office of Civilian Defense as a volunteer without pay. She would also do a series of

radio broadcasts that focused on how women could help with the war effort. With these new duties added to her extensive writing and speaking commitments and her obligations as first lady, she rarely logged less than fifteen hours of work each day.

In March, ER went to

Tuskegee Institute, in Alabama, to meet with the

Julius Rosenwald Fund’s board of trustees. On the agenda was a request for a loan from institute president

Frederick D. Patterson to expand the facilities for the all-black flight-training program at the school. Mary McLeod

Bethune had been lobbying FDR to end the

military’s “

flagrant discrimination against Negroes” and to allow them to be trained as pilots.

The first lady, a Rosenwald

Fund trustee, visited the flight-training program. The staff and trainees impressed her. Hoping to convince the administration and the public that blacks could fly, she decided to be photographed in a Waco biplane piloted by Charles

Anderson, the first African American to earn a pilot’s license and the program’s chief flight instructor. When ER announced her intention to fly with Anderson,

“the

Secret Service men almost had a conniption, but what can you tell

the First Lady when she says, ‘I’m going to do this’?” observed Quentin Smith, a pilot in training.

ER had always loved flying. “

It was like being on top of the world,” she had said of her 1933 round-trip flight from Washington to Baltimore in a plane piloted by

Amelia Earhart, the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean. On this day, ER savored the breathtaking

view of the Alabama “countryside” for forty minutes from the passenger seat of the small plane. With pride, she presented a snapshot of herself and her confident pilot to FDR. That snapshot appeared in newspapers across the country.

ER encouraged the fund trustees to support the project, and she kept a watchful eye on the squadron that came to be known as the Tuskegee Airmen—or the Red Tails, in deference to the paint on the tail section of their planes. They would distinguish themselves under the command of the black West Point graduate Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin O.

Davis Jr. The Tuskegee Airmen would “

bless…the name of Eleanor Roosevelt” for the rest of their lives.

· · ·

IN DIRE NEED OF RESPITE

, Murray accepted an offer from the

Young People’s Socialist League to do a series of talks on sharecropping during the summer in exchange for free housing in a secluded cabin atop

Mount Airy, in the Catskills.

In this tranquil place, she set her troubles aside and established, for the first time, a daily

writing practice. Getting to put her writer self at the forefront of her consciousness was a wondrous experience. She “

avoided causes and politics,” she wrote in her

journal, like “poison ivy.”

Murray wrote in the nude, except for a pair of shorts, on a small screened porch attached to her two-room cabin. Sometimes it took her all day, typing and retyping, to eke out a page. Whenever she hit writer’s block, she took off for the woods with her dog,

Petie. Walking away from the writing when frustrated seemed to refuel Murray’s creativity. She often raced back to the

typewriter to catch sentences that had sprung into her mind.

The combination of uninterrupted time, release from the strain of the campaign, and reassuring feedback from the Pulitzer Prize–winning

poet

Stephen Vincent Benét improved Murray’s outlook.

John Brown’s Body

, Benét’s epic poem about the

Civil War, was one of her favorites. Reading it always drew her close emotionally to Grandfather Robert, a Civil War veteran who’d left a diary of his experience.

Murray had written to

Benét two years earlier, introduced herself, and asked him to read her work.

He’d responded with an invitation to meet at his New York City residence. Their periodic meetings and Benét’s written critiques nurtured her epic poem “Dark Testament” and a series of sketches that would mature into the

family memoir

Proud Shoes

.

The Waller campaign, on the other hand, pulled Murray toward a law

career. Indeed, each encounter she had with

Leon Ransom or

Thurgood Marshall seemed to quicken the path away from creative writing. Ransom, who’d witnessed Murray’s presentation to the black ministers in Richmond, had complimented her on her appeal. To deflect the conversation from what she felt was a shamefaced performance, Murray quipped that she “

might as well become a lawyer” since she kept “bumping into the law.” Ransom took her words literally. He told her she “

had what it takes to become a good lawyer,” and he urged her to come to

Howard University School of Law. Skeptical of his offer and her ability, Murray said that she might, if she got a scholarship. Ransom pledged that she would get one, if she applied.

Murray remained ambivalent about pursing a law degree despite Ransom’s encouragement and a letter of recommendation from Marshall. The day notice of her acceptance and a tuition scholarship arrived, she faced a dilemma: Should she become a writer or a lawyer? “

I’m really a submerged writer,” Murray told writers

Lillian E. Smith and

Paula Snelling, “but the exigencies of the period have driven me into social action.” Murray capulsized her situation in the opening lines of the poem

“

Conflict”: