The Firebrand and the First Lady: Portrait of a Friendship: Pauli Murray, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the Struggle for Social Justice (54 page)

Authors: Patricia Bell-Scott

Tags: #Political, #Lgbt, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #20th Century

The resistance to Murray was an omen for those who would follow her. Both

Barbara Harris, an African American who became the first woman consecrated as a bishop, in 1989, and

Gene Robinson, the first openly gay bishop approved by the General Convention, in 2003, would face hate mail and

death threats during their tenure.

The consecration of

Mary Glasspool as the first openly

lesbian bishop, in 2010, would be condemned by Archbishop of Canterbury

Rowan Williams. Just as Murray paved the way for Harris, Robinson, Glasspool, and others, progressives would lay the ground for her elevation by the Episcopal Church to

sainthood in July 2012, twenty-seven years after her death.

By naming Murray to

Holy Women, Holy Men

, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church deemed that her life and contributions would be honored and celebrated on the anniversary of her death.

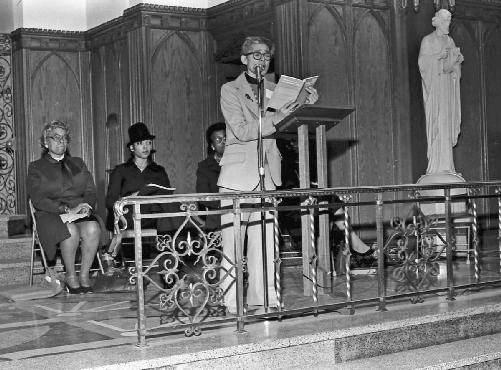

The Reverend Dr. Pauli Murray (front) and unidentified speakers (seated at rear) at the Salute to Black Women program, Metropolitan Baptist Church, Washington, D.C., February 5, 1977. Murray carried her ministry into churches and nursing homes in Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the nation’s capital.

(Courtesy of Milton Williams)

64

“God’s Presence Is as Close as the Touch of a Loved One’s Hand”

O

n February 13, a month after her ordination, Pauli Murray celebrated her first Holy

Eucharist at the

Chapel of the Cross in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. She was the first woman to perform the Eucharist at the old church and in the state of North Carolina. In the racially mixed congregation of six hundred sat journalist and UNC alumnus

Charles Kuralt, who filmed the service and interviewed Murray for his popular CBS television series

On the Road

.

The elaborate lectern behind which Murray stood bore the name of her slaveholding great-aunt,

Mary Ruffin Smith, who had bequeathed a portion of her inheritance to the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina. The fragile

Bible Murray held was a treasured gift from Smith to her niece, Murray’s

grandmother Cornelia, whose baptism as one of Smith’s “

five servant children” was recorded on December 20, 1858, in the church registry. The purple ribbon and dried flowers Murray used as a Bible bookmark had come with the bouquet Eleanor Roosevelt had sent thirty-three years ago when Murray graduated from

Howard University School of Law.

“

That the first woman priest to preside at the altar of the church to which Mary Ruffin Smith had given her deepest devotion should be the granddaughter of the little girl she had sent to the balcony reserved for slaves” was a remarkable irony that Murray felt deeply. It was indeed a “

historic moment,” she told Kuralt, in that she symbolized those who had suffered in the past because of “

race, color, religion, sex (gender), age, sex preference, political and theological differences, economic and

social status, and other man-made barriers.” These souls, she insisted, were “

reaching out” through her in love and reconciliation.

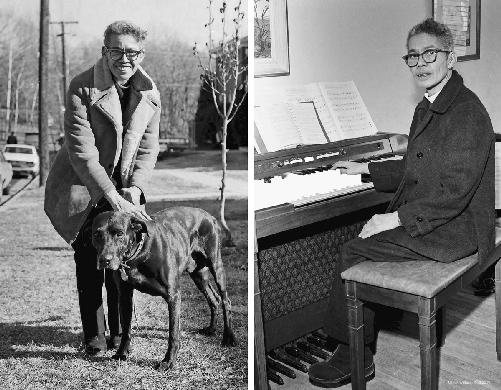

Murray with her dog Roy (left) and playing her organ (right), Alexandria, Virginia, 1976. She slept very little and considered television a waste of time.

(Courtesy of Milton Williams)

Murray was the oldest practicing female Episcopal priest and still a maverick.

She wore pants and ski caps for comfort. She carried her writing tools in a backpack wherever she went. After forced retirement at age seventy-two, she would continue to serve the aged, the sick, the shut-in, and those grieving the loss of loved ones.

She was among the clergy who participated in the funeral services for Alice Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party and author of the original version of the Equal Rights Amendment, and for Dorothy Kenyon, who had been a role model and colleague.

Murray’s sermons were an inspiring blend of Holy Scripture, poetry, philosophy, and personal narrative. Her favorite material came from Bible stories of women, like Mary Magdalene; Kahlil Gibran’s

The Prophet;

the writings of Paul Tillich; and her experiences with Grandmother Cornelia, Aunts Pauline and Sallie, Renee, and ER. The spirit of

“God’s presence,” Murray often said, “is as close as the touch of a loved one’s hand.”

Murray may have thought that becoming a priest would quiet her restless spirit and assuage her grief. This was not to be. Life was as intense as ever. Her longing for

“a friend of the heart” remained unabated, as did her addiction to unfiltered cigarettes and strong coffee. Her small apartment, she quipped, was

“a library with a few chairs.”

Murray’s loving embrace always included dogs. Six weeks after Doc died, she met Roy, a two-year-old black Labrador retriever, in a veterinarian’s office, waiting to be put down after a hit-and-run driver had crushed his left hind leg. Murray could not bear the thought of Roy dying alone, so she took him home and nursed him. He rallied, and Murray had his leg surgically repaired. Roy would run, swim, and happily fetch sticks until his death, a decade later.

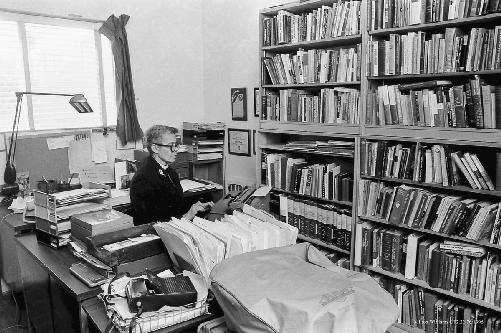

Murray at her home office in Alexandria, Virginia, 1976. Writing was Murray’s salvation, and her tools were rarely more than an arm’s length away.

(Courtesy of Milton Williams)

65

“Hopefully, We Have Picked Up the Candle”

D

oing “

a creditable piece of writing” had always given Murray “a sense of self-worth,” and she felt an urgent need to write a sequel to

Proud Shoes

. As she worked on what would become her autobiography, she sought to examine her life in historical perspective. Of the books Murray consulted on the twentieth century and the lives of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, those by

Stella K. Hershan and

Joseph P. Lash touched her in a unique way.

Hershan’s

A Woman of Quality

, published in 1970, was a collection of interviews with people who believed ER had changed the course of their lives. Hershan profiled people ER met by chance, such as cab drivers; those in whom she took a special interest, such as children, American and Israeli Jews, labor organizers, minorities, refugees, the disabled, and wounded soldiers; and those with whom she had worked, such as the

staff and alumni of the Wiltwyck School, former members of her household staff, and her colleagues at the United Nations.

Hershan interviewed Murray for the chapter titled “The Negroes.”

Among the stories Murray recounted was the case of the black seamen accused of mutiny after the explosion at Port Chicago and

ER’s gallant, albeit unsuccessful, effort to convince the navy to grant them clemency. Murray “

choked up” during the interview, and Hershan, an Austrian-born

Jew who’d fled her homeland to escape the Nazis, became emotional, too.

Both knew the heartache of injustice and the healing power of ER’s accepting presence.

Murray knew Joseph Lash through ER and the network of progressives close to her. Born in New York City to Russian Jewish immigrant parents, Lash, like Murray, was a former student activist whom ER befriended in the late 1930s. A journalist with a keen sense of history, Lash had helped ER organize her

papers before she donated them to the

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Presidential Library. Two years after ER’s death, Lash published

Eleanor Roosevelt: A Friend’s Memoir

. In 1971, he published

Eleanor and Franklin: The Study of Their Relationship Based on Eleanor Roosevelt’s Private Papers

, for which he earned the

Pulitzer Prize in biography. He followed with

Eleanor: The Years Alone

in 1972.

In

Eleanor and Franklin

, Lash excerpted the letter Murray wrote to FDR after his

University of North Carolina address along with her

poem “Mr. Roosevelt Regrets.” Impressed with his work, Murray responded with an effusive letter. “

Joe,” she began, “it is magnificently beautiful!…I have to read slowly savoring each line and some of the sharply insightful passages.… You are an artist, writing lovingly, tenderly and gracefully.… This book will LIVE and do pride to Mrs. R’s memory.” Reading Lash’s footnotes made Murray feel like “

a miser,” she confessed, for she had a large file of

correspondence he had not seen. She had planned to give the documents to the FDR Library, but she

“cherished

Mrs. Roosevelt’s letters so” that she had “been unable to part with them.”

Lash was curious about Murray’s file, and he asked if she would permit him to examine the correspondence, especially those with ER’s handwritten postscripts and margin notes. “

On the other hand,” he wrote, “you are probably planning to write something yourself and if you want to save those letters for your own autobiography, I will understand fully a decision to keep your correspondence with Mrs. R. to yourself.”

“Joe,” Murray replied, “the great lesson Mrs. R. taught all of us by example was largesse, generosity—her heart seemed to me as big as all the world.… She belongs to history, and the impact of her spirit is sorely

needed now in our sorrowful society which seems to have fallen on bad days in many respects. If there is anything in her correspondence with me or mine with her which will sharpen the impact of her great spirit of compassion, of caring for people, of keeping track of people no matter how busy she was—then use it now,” Murray insisted. “I do not believe your use of such material will detract from anything I should write in the future—because our experiences are different and by the time I get around to full-time writing, history will have moved on. New insights will arise which will make my approach using the same material different from yours.” On the chance that her literary agent “might not agree,” Murray decided not to “consult her on this one.”

When Murray began to write in earnest, Lash was at work on two collections of letters.

Love, Eleanor: Eleanor Roosevelt and Her Friends

was released in 1982, and

A World of Love: Eleanor Roosevelt and Her Friends, 1943–1962

appeared two years later.

While he mentioned Murray in

A World of Love

, not one of the letters she and ER wrote to each other in their decades-long friendship appeared in full or excerpt in either collection. Considering the access Murray gave Lash, she must have been disappointed.

· · ·

IN JULY 1982

, Murray had emergency surgery at

Johns Hopkins

Hospital for a life-threatening

intestinal blockage.

Maida Springer-Kemp, who now lived in Pittsburgh, came to nurse Murray back to

health.

This crisis and the demands of her ministry thwarted Murray’s writing. When the

Eleanor Roosevelt Centennial Committee invited her to contribute to a book of essays, she was unable to participate.

Even so, the outline of the project prompted Murray to write to the editors.

The first concern was “

the absence of an author (so far as the names suggest),” Murray observed, “who is obviously a Negro/Black/Person of color/Afro-American—I prefer Negro. Given Mrs. Roosevelt’s deep involvement in

civil rights issues, it would be a grave oversight not to have a Negro author represented.” (Murray recommended

Pauline Redmond Coggs.) Another issue was the project’s primary focus on ER’s political life. “Mrs. Roosevelt was much more than a political animal,” she maintained, and “the book would have more intrinsic value if the personal and the political are brought together in these essays as they were indeed reflected in her life.”