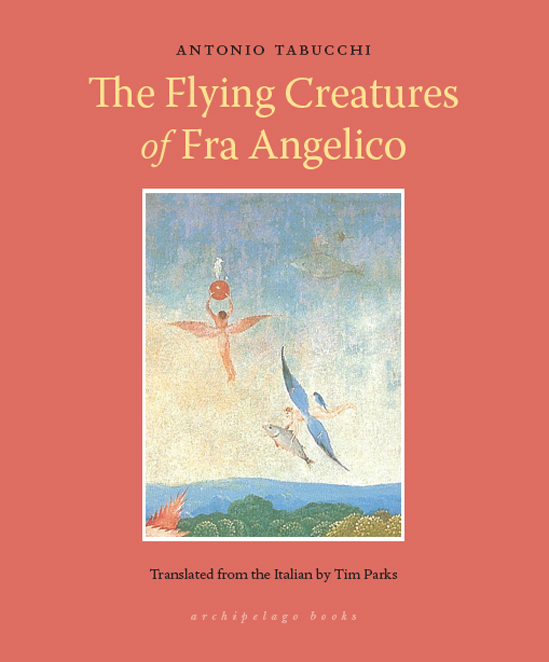

The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico

Read The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico Online

Authors: Antonio Tabucchi

The Flying Creatures

of

Fra Angelico

Translated from the Italian by Tim Parks

a

r

c

h

i

p

e

l

a

g

o

b

o

o

k

s

Copyright © Antonio Tabucchi, 2013

English language translation © Tim Parks, 1991

First Archipelago Books Edition, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

First published as

I volatili del Beato Angelico

by Sellerio editore in 1987.

Archipelago Books

232 3rd Street #

A111

Brooklyn, NY 11215

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tabucchi, Antonio, 1943â2012.

[Volatili del Beato Angelico. English]

The flying creatures of Fra Angelico/by Antonio Tabucchi;

translated from the Italian by Tim Parks.â1st Archipelago Books ed.

p. cm.

“First published I volatili del Beato Angelico by Sellerio editore in 1987”âT.p. verso.

ISBN

978-1-935744-57-3

1. Short stories, ItalianâTranslations into English. I. Parks, Tim. II. Title.

PQ4880.A24V6513 2013

853'.914âdc22

2012025598

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

Cover art: Hieronymus Bosch, detail from

The Garden of Earthly Delights

The publication of

The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico

was made possible with support from Lannan Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.

The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico

I Letter from Dom Sebastião de Avis, King of Portugal

,

to Francisco Goya, painter

II Letter from Mademoiselle Lenormand, fortune-teller

,

to Dolores Ibarruri, revolutionary

III Letter from Calypso, a nymph, to Odysseus,

King of Ithaca

âThe phrase that follows this is false: the phrase

that precedes this is true'

Hypochondria, insomnia, restlessness and yearning are the lame muses of these brief pages. I would have liked to call them

Extravaganzas

, not so much for their style, as because many of them seem to wander about in a strange outside that has no inside, like drifting splinters, survivors of some whole that never was. Alien to any orbit, I have the impression they navigate in familiar spaces whose geometry nevertheless remains a mystery; let's say domestic thickets: the interstitial zones of our daily having-to-be, or bumps on the surface of existence.

Then some of these pages, as for example “The Archives of Macao” and “Past Composed: Three Letters,” are eccentric even on their own terms, refugees from

the idea that originated them. To the extent that they are fragments of novels and stories, they are no more than meagre conjectures, or spurious projections of desire. They have a larval nature: they present themselves like creatures under formalin, with the oversize eyes of organisms still in the foetal stage â questioning eyes. But questioning whom? What do they want? I don't know if they're really questioning anyone, nor if they want anything, but I feel it would be kinder to ask nothing of them, since I believe that asking questions is the prerogative of those beings Nature has not brought to completion: it is that which is clearly incomplete that has the right to ask questions. Still, I cannot deny that I love them, these sketchy compositions entrusted to a notebook which out of an unconscious sort of faithfulness I have carried around with me constantly these last few years. In them, in the form of quasi-stories, are the murmurings and mutterings that have accompanied and still accompany me: outbursts, moods, little ecstasies, real or presumed emotions, grudges and regrets.

So that rather than quasi-stories, perhaps I should

say that these pages are no more than background noise in written form. Had I been a little more ruthless with myself, I would have called the collection

Buridan's Ass

. What stopped me from doing that, apart from a residual pride, which is often no more than a sublimated form of baseness, was the idea that although choice and completeness are not granted to the slothful wrapped up in their background noises, one is nevertheless still left with the chance of a few meagre words: so one may as well say them. A kind of awareness, this, not to be confused with noble stoicism, and not with resignation either.

A.T.

Some of these pieces have already been published in Italian or foreign reviews, though it would be difficult for me to supply an exact bibliography. All the same I would like to mention the original publications of two pieces which are linked to friends. Of the letters that make up “Past Composed,” published in

Il cavallo di Troia

, no. 4, 1983â84, the one from Dom Sebastião of Portugal to Francisco Goya was dedicated to José Sasportes, and I would like to renew that dedication. “Message from the Half Dark” appeared in the catalogue (published by the Comune di Reggio Emilia, 1986) for a show of paintings by Davide Benati entitled

Terre d'ombre.

The piece is inspired by his paintings.

of

Fra Angelico

The Flying Creatures of Fra Angelico

The first creature arrived on a Thursday towards the end of June, at vespers, when all the monks were in the chapel for service. Privately, Fra Giovanni of Fiesole still thought of himself as Guidolino, the name he had left behind in the world when he came to the cloister. He was in the vegetable garden gathering onions, which was his job, since in abandoning the world he hadn't wanted to abandon the vocation of his father, Pietro, who was a vegetable gardener, and in the garden at San Marco he grew tomatoes, courgettes and onions. The onions were the red kind, with big heads, very sweet after you'd soaked them for an hour, though they made you cry a fair bit when you handled them. He was putting them

in his frock gathered to form an apron, when he heard a voice calling: Guidolino. He raised his eyes and saw the bird. He saw it through onion tears filling his eyes and so stood gazing at it for a few moments, for the shape was magnified and distorted by his tears as though through a bizarre lens; he blinked his eyes to dry the lashes, then looked again.

It was a pinkish creature, soft looking, with small yellowish arms like a plucked chicken's, bony, and two feet which again were very lean with bulbous joints and calloused toes, like a turkey's. The face was that of an aged baby, but smooth, with two big black eyes and a hoary down instead of hair; and he watched as its arms floundered wearily, as if unable to stop itself making this repetitive movement, miming a flight that was no longer possible. It had got caught up in the branches of the pear tree, which were spiky and warty and at this time of year laden with pears, so that at every one of the creature's movements, a few ripe pears would fall and land splat on the clods beneath. There it hung, in a very uncomfortable position, feet straddled over two branches which must be

hurting its groin, torso sideways and neck twisted, since otherwise it would have been forced to look up in the air. From the creature's shoulder blades, like incredible triangular sails, rose two enormous wings which covered the entire foliage of the tree and which moved in the breeze together with the leaves. They were made of different coloured feathers, ochre, yellow, deep blue, and an emerald green the colour of a kingfisher, and every now and then they opened like a fan, almost touching the ground, then closed again, in a flash, disappearing behind each other.

Fra Giovanni dried his eyes with the back of his hand and said: “Was it you called me?”

The bird shook his head and, pointing a claw like an index finger towards him, wagged it.

“Me?” asked Fra Giovanni, amazed.

The bird nodded.

“It was me calling me?” repeated Fra Giovanni.

This time the creature closed his eyes and then opened them again, to indicate yes once again; or perhaps out of tiredness, it was hard to say: because he was tired, you

could see it in his face, in the heavy dark hollows around his eyes, and Fra Giovanni noticed that his forehead was beaded with sweat, a lattice of droplets, though they weren't dripping down; they evaporated in the evening breeze and then formed again.

Fra Giovanni looked at him and felt sorry for him and muttered: “You're overtired.” The creature looked back with his big moist eyes, then closed his eyelids and wriggled a few feathers in his wings: a yellow feather, a green one and two blue ones, the latter three times in rapid succession. Fra Giovanni understood and said, spelling it out as one learning a code: “You've made a trip, it was too long.” And then he asked: “Why do I understand what you say?” The creature opened his arms as far as his position allowed, as if to say, I haven't the faintest idea. So that Fra Giovanni concluded: “Obviously I understand you because I understand you.” Then he said: “Now I'll help you get down.”

Standing against a cherry tree at the bottom of the garden was a ladder. Fra Giovanni went and picked it up, and, holding it horizontally on his shoulders with his

head between two rungs, carried it over to the pear tree, where he leaned it in such a way that the top of the ladder was near the creature's feet. Before climbing up, he slipped off his frock because the skirts cramped his movements, and draped it over a sage bush near the well. As he climbed up the rungs he looked down at his legs, which were lean and white with hardly any hairs, and it occurred to him they looked like the bird creature's. And he smiled, since likenesses do make one smile. Then, as he climbed, he realised his private part had slipped out of the slit in his drawers and that the creature was staring at it with astonished eyes, shocked and frightened. Fra Giovanni did himself up, straightened his drawers and said: “I'm sorry, it's something we humans have”; and for a moment he thought of Nerina, of a farmhouse near Siena many years before, a blonde girl and a straw rick. Then he said: âSometimes we manage to forget it, but it takes a lot of effort and a sense of the clouds above, because the flesh is heavy and forever pulling us earthwards.'

He grabbed the bird creature by the feet, freed him from the spikes of the pear tree, made sure that the

down on his head didn't catch on the twigs, closed his wings, and then with the creature holding on to his back, brought him down to the ground.