The Gardens of Democracy: A New American Story of Citizenship, the Economy, and the Role of Government (11 page)

Authors: Eric Liu,Nick Hanauer

Tags: #Political Science, #Political Ideologies, #Democracy, #History & Theory, #General

BOOK: The Gardens of Democracy: A New American Story of Citizenship, the Economy, and the Role of Government

5Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

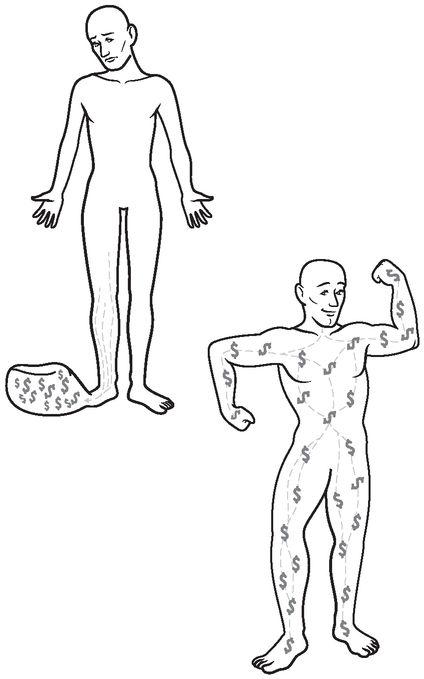

Massive concentration of wealth is unhealthy

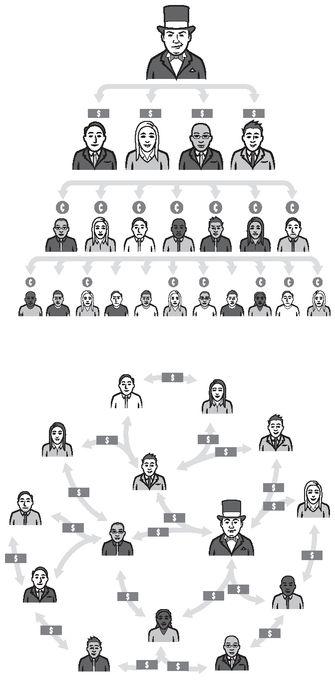

Our program is the antithesis of trickle-down theory. It’s what we call middle-out economics, and its essence is simple: circulate wealth in ways that bring prosperity to the middle class so that it can buy goods and services and set in motion a feedback loop that benefits everyone—rich and poor—over the long term. Middle-out economics does not rely on the droppings of the super-rich. It starts with the broad middle to generate wealth and pushes that wealth outward so that it can circulate throughout the economy.

Trickle-down economics takes care of a few great men, on the mistaken idea that we can count on them to create jobs for the rest of us. Middle-out economics starts with the rest of us. It says that we are the engine of wealth creation. When the broad middle has the earning power to drive an economy, everybody is better off—including wealthy entrepreneurs who meet the demand of the middle. Even a hard-nosed industrialist like Henry Ford understood this when he paid his assembly line workers higher wages than the market said he needed to—not out of altruism but out of a long-term understanding that his employees were going to be his customers and needed to be able to afford a Model T.

Trickle-down economics means lower income taxes on the rich, lower capital gains taxes, lower estate taxes, lower regulation, and lower investment in public goods like education and infrastructure. It is about empowering the few on the theory that the many can derive second-order benefits. Its action is top-down.

Middle-out economics means investing aggressively in the middle class, more focus on education and infrastructure, higher wages, and strategic public-private investment in high-potential arenas coupled with strongly progressive taxation and aggressive estate taxation. It is about empowering the many so that the few can derive second-order benefits—and set in motion another cycle of prosperity. Its action is middle-out.

Trickle-down vs. Middle-out economics

Progressive taxation is one key here. It blunts the natural mathematical tendency of markets to concentrate into winner-take-all monopolies. It keeps the economy healthy by circulating resources back into the general economy and thus sets off cycles of ever-increasing prosperity, opportunity, and comparative advantage. Another key is a robust and adaptive labor union movement—willing to push management

and

decalcify itself—to help workers increase productivity and then share in the gains of that productivity. Unions are a vital counterweight to concentrated corporate power. But they can become protectionist in their own right, indulging in the kind of zero-sum thinking that makes any adaption seem like an unacceptable concession.

and

decalcify itself—to help workers increase productivity and then share in the gains of that productivity. Unions are a vital counterweight to concentrated corporate power. But they can become protectionist in their own right, indulging in the kind of zero-sum thinking that makes any adaption seem like an unacceptable concession.

Middle-out economics is not about being anti-rich. It’s about making everyone richer over the long haul. It returns to a simple idea that Gardenbrain economics teaches: we are all better off when we are all better off. No one benefits more in the long term from recirculation of wealth through taxes and government spending than the rich or those who wish to be rich. An economy where 300 million citizens are vibrant consumers is a high-growth, high-profit, high-multiple economy. For the wealthy to pay a bit more in taxes now for that kind of economy later is good business.

We state simply that excessive concentration always harms the whole. Blood should flow from the core outward, not from a swollen extremity to the rest of the body. To put it in economic terms, wealth should be generated by, from, and for the middle class in ways that intentionally benefit the broad middle and only incidentally (though inevitably) benefit the wealthy few.

There are five core principles that undergird middle-out economics:

Grow from the middle out.

Our theory of action takes Ford’s insight and amplifies it: foster a healthy middle-class customer base with purchasing power and everyone will get richer. Create a positive feedback loop of prosperity by investing in the middle class. Our theory also says that “government spending” is not a one-time dump of cash into a rat hole; whether it’s Social Security or education, it’s just good recirculation. This is the approach the United States applied in the first three decades after World War II, a period of prosperity unparalleled in how sustainable and broadly shared it was.

Our theory of action takes Ford’s insight and amplifies it: foster a healthy middle-class customer base with purchasing power and everyone will get richer. Create a positive feedback loop of prosperity by investing in the middle class. Our theory also says that “government spending” is not a one-time dump of cash into a rat hole; whether it’s Social Security or education, it’s just good recirculation. This is the approach the United States applied in the first three decades after World War II, a period of prosperity unparalleled in how sustainable and broadly shared it was.

Maximize the number of able, diverse competitors.

The point of the economy—particularly in a democracy—is not to enrich the few but to empower the many. For a nation to thrive and to win in a global economic competition, it needs to put as many players on the field as it can. As the complexity theorist Scott Page has argued in

The Difference

, “diversity trumps ability.” That is, the ability of a society to solve its problems is more dependent on the diversity of approaches it takes than on the ability of a few individuals. Diversity is not only nice and inclusive ; it is smart and effective. This means ensuring that

all

our children get a healthy start. It means enabling more of our people to get the education they need to be generators of new ideas and skillful contributors to innovation ecosystems. It means increasing access to capital for aspiring small businesspeople of limited means. It means shifting our asset policies so that incentives to save, which today are tilted toward the already affluent, can be used to give working Americans a leg up. America leaves far too much talent untapped. Bad schools, poor health, unsafe neighborhoods, the absence of job skill ladders—all these keep a great proportion of our human power inactive.

The point of the economy—particularly in a democracy—is not to enrich the few but to empower the many. For a nation to thrive and to win in a global economic competition, it needs to put as many players on the field as it can. As the complexity theorist Scott Page has argued in

The Difference

, “diversity trumps ability.” That is, the ability of a society to solve its problems is more dependent on the diversity of approaches it takes than on the ability of a few individuals. Diversity is not only nice and inclusive ; it is smart and effective. This means ensuring that

all

our children get a healthy start. It means enabling more of our people to get the education they need to be generators of new ideas and skillful contributors to innovation ecosystems. It means increasing access to capital for aspiring small businesspeople of limited means. It means shifting our asset policies so that incentives to save, which today are tilted toward the already affluent, can be used to give working Americans a leg up. America leaves far too much talent untapped. Bad schools, poor health, unsafe neighborhoods, the absence of job skill ladders—all these keep a great proportion of our human power inactive.

Break up opportunity monopolies.

It is a fact of economic life that both advantage and disadvantage compound. What we end up with are opportunity monopolies dotting and clotting the economic landscape. When we tax what Teddy Roosevelt called the “swollen fortunes” of a tiny few—vast fortunes made possible by the investments in public goods by prior generations—and recirculate that wealth in public goods like schools and health care so that the middle and bottom can participate in the economy—we are doing something good for the many

and

, in the long run, for the few. Hoarding may feel like the rational thing for the rich, but it is against their true self-interest, which is found not in clotting but in circulation to the whole. Concentrations of poverty follow concentrations of wealth. This is why we need to return to progressive taxation and much higher marginal rates on high-income Americans—not to punish success but to create the conditions for more success for more people. It’s why America needs an extensive class-based affirmative action program to ensure that there is true competition of talent. It’s why there needs to be a massive rebalancing of our asset and tax incentive policies, which today are invisibly coring the middle class and directing $400 billion a year to the already affluent or wealthy. The richest 5 percent of Americans get more than half of all the benefits of the exemptions and deductions in the tax code. We must realign our asset and tax-expenditure policy so that loopholes and tax benefits work to benefit the not-rich rather than further fatten the already rich. It is why we need to invest the revenues from these first two steps into research and development and incentives for the formation of businesses that create jobs in America—not for the illusory products of our metastasizing financial sector.

It is a fact of economic life that both advantage and disadvantage compound. What we end up with are opportunity monopolies dotting and clotting the economic landscape. When we tax what Teddy Roosevelt called the “swollen fortunes” of a tiny few—vast fortunes made possible by the investments in public goods by prior generations—and recirculate that wealth in public goods like schools and health care so that the middle and bottom can participate in the economy—we are doing something good for the many

and

, in the long run, for the few. Hoarding may feel like the rational thing for the rich, but it is against their true self-interest, which is found not in clotting but in circulation to the whole. Concentrations of poverty follow concentrations of wealth. This is why we need to return to progressive taxation and much higher marginal rates on high-income Americans—not to punish success but to create the conditions for more success for more people. It’s why America needs an extensive class-based affirmative action program to ensure that there is true competition of talent. It’s why there needs to be a massive rebalancing of our asset and tax incentive policies, which today are invisibly coring the middle class and directing $400 billion a year to the already affluent or wealthy. The richest 5 percent of Americans get more than half of all the benefits of the exemptions and deductions in the tax code. We must realign our asset and tax-expenditure policy so that loopholes and tax benefits work to benefit the not-rich rather than further fatten the already rich. It is why we need to invest the revenues from these first two steps into research and development and incentives for the formation of businesses that create jobs in America—not for the illusory products of our metastasizing financial sector.

Promote true competition.

In American policy today, we don’t help people become rich; we reward the already rich for being rich. When you look at it closely, the ersatz capitalism of Wall Street and market fundamentalists is actually quite protectionist. The ideology of “free enterprise,” as preached by anti-tax and anti-regulation activists, is used to prevent change to the current arrangement of economic power: don’t regulate my company, don’t touch my money, don’t let more people in on the game I’ve rigged. Socialize losses, privatize profits. It’s about defending capitalists; not capital

ism.

Such a defense of the current distribution of wealth might be tolerable if the status quo allowed for every American to compete purely on the basis of talent and merit. Do you really think it does? True capitalism is about making sure everyone is on the playing field, not just those who can afford the equipment. It is about upending the order of things continuously, not defending it. True capitalism is more competitive because it’s more fair, and more fair because it’s more competitive.

In American policy today, we don’t help people become rich; we reward the already rich for being rich. When you look at it closely, the ersatz capitalism of Wall Street and market fundamentalists is actually quite protectionist. The ideology of “free enterprise,” as preached by anti-tax and anti-regulation activists, is used to prevent change to the current arrangement of economic power: don’t regulate my company, don’t touch my money, don’t let more people in on the game I’ve rigged. Socialize losses, privatize profits. It’s about defending capitalists; not capital

ism.

Such a defense of the current distribution of wealth might be tolerable if the status quo allowed for every American to compete purely on the basis of talent and merit. Do you really think it does? True capitalism is about making sure everyone is on the playing field, not just those who can afford the equipment. It is about upending the order of things continuously, not defending it. True capitalism is more competitive because it’s more fair, and more fair because it’s more competitive.

Harness market forces to national goals.

Economic right-wingers insist that heroic individuals “do it themselves” and that such people are “self-made.” This claim does not hold up under any serious scrutiny. Ford could not have created an auto industry without the roads necessary for them to travel on. He did not build those roads, let alone mark or map them. Amazon and Google did not create the Internet; the federal government did. No company in America has provided the infrastructure that made its lines of businesses possible, much less educated its own workforce. The question is not whether to have government in the economy but how wisely to deploy it. Government’s job, in collaboration with the private sector, is to set great goals. The market’s job is to unleash a truly competitive frenzy in pursuit of those goals.

We’re All Better Off When We Are All Better OffEconomic right-wingers insist that heroic individuals “do it themselves” and that such people are “self-made.” This claim does not hold up under any serious scrutiny. Ford could not have created an auto industry without the roads necessary for them to travel on. He did not build those roads, let alone mark or map them. Amazon and Google did not create the Internet; the federal government did. No company in America has provided the infrastructure that made its lines of businesses possible, much less educated its own workforce. The question is not whether to have government in the economy but how wisely to deploy it. Government’s job, in collaboration with the private sector, is to set great goals. The market’s job is to unleash a truly competitive frenzy in pursuit of those goals.

Limited-government advocates say they don’t trust the government to spend your money. We say why trust the super-rich to spend your money? We say why not trust the people of the middle class to spend their own money? Like the trickle-down economics crew, we believe there is a goose that lays a golden egg in our economy. They think the goose is the top 1 percent. We think it’s the broad middle class.

They think we’re all better off when the rich are better off. We think we’re all better off when we are

all

better off.

They think we’re all better off when the rich are better off. We think we’re all better off when we are

all

better off.

We believe that nurturing an economy from the middle out and the bottom up is how this country can achieve and sustain real—earned, and unborrowed—prosperity of the kind that trickle-down has never once delivered.

To be sure: government needs to be smarter and more efficient in its role as circulator and investor. And there is no question that the animal spirits of capitalism and markets remain an unsurpassed force for innovation and solutions. We are pro-capitalism. In fact, we are fiercely so. What that requires is remembering what capitalism is supposed to be about—generating the most widespread competition possible so that society gets the most fruitful results possible.

Some may claim that we are calling for totalitarian leveling, for equality of outcomes. Absolutely not. A certain amount of inequality is inevitable and even beneficial. But we simply point out that too much inequality is as fatal to society as enforced equality. The distribution curve should look more like a bell than a hockey stick, with a big sweet spot of prosperity and security—as it was in the 1950s and 1960s. Unfortunately, since the 1980s, we have had the hockey stick.

The choice facing the United States is simple. Free-lunch trickle-down economics sounds great but is a proven loser. Grown-up middle-driven economics sounds harder but will get us back on track as a country. We can have an economy with only a few winners, or an economy where everyone who works hard wins.

Imagine two gardeners with plots of land side by side. The first rakes the seed so that it’s spread more evenly; the second lets it be. When the seeds begin to sprout weeks later, the first gardener has fruit and vegetables all across her plot; the second has plants where the seed had clumped but otherwise barren land.

Other books

Natural Flights of the Human Mind by Clare Morrall

Basic Principles of Classical Ballet by Vaganova, Agrippina

The Burning Horizon by Erin Hunter

Monstrous Beauty by Elizabeth Fama

Touched by Lilly Wilde

Blake: A Bad Boy Romance by Day, Laura

Unknown by Unknown

Jalia on the Road (Jalia - World of Jalon) by John Booth

Shroud by John Banville

Strife: Part Two (The Strife Series Book 2) by Corgan, Sky