The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine (31 page)

Read The General's Son: Journey of an Israeli in Palestine Online

Authors: Miko Peled

Tags: #BIO010000

Mazen’s father, Ali Faraj, 62, was killed in April 2002 during the second Intifada. He went out to buy food for the family and while he was gone, the Israeli authorities imposed a curfew on the camp. Being gone from the camp he didn’t realize the curfew was in effect and when he returned, an Israeli tank fired at him and killed him. Then, the Israeli authorities immediately arrested Mazen and kept him under administrative detention for several months. He was targeted because he was the youngest of all his brothers, and the only one who was not yet married. Therefore it was assumed he posed a threat and might try to take revenge.

It was soon time for lunch and the two of us drove to his house in Deheishe. This was my first visit to any refugee camp. In the decades since it was established, Deheishe has become a bustling, disorganized, and overcrowded little town. Its 13,000 residents live on one-quarter of a square mile. All of them are either from or are descendants of people who were from villages around Jerusalem that were destroyed when Israel was established.

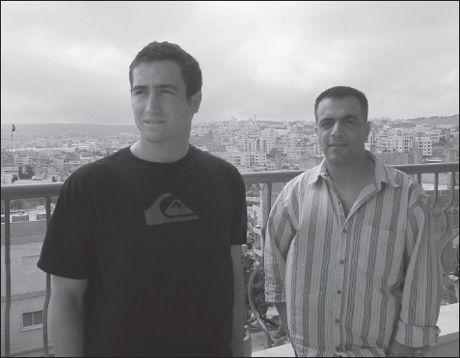

My friend Mazen Faraj on the right with Eitan at Deheishe Refugee Camp.

We had lunch and coffee at Mazen’s house with his wife and two daughters (I later brought Eitan with me to visit them as well), and then Mazen took me to the Phoenix House, or

El-Feneiq,

a spacious community center that offers kids in Deheishe free after-school activities and camps when school is out. Young college kids who volunteer conduct the activities. Since there are no parks or playgrounds and no swimming pool, putting together activities for kids takes creativity and a lot of dedication. The volunteers I met there, young men and women, had both.

“Why is there no pool?” I asked one of the volunteers who showed me around the center.

“We have no water.”

I did not understand.

“All the water supply is controlled by Israel and sometimes the authorities shut the water supply and the camp goes for days without water. You cannot have a pool when you don’t even have enough water to drink and wash.” Then he smiled: “But we have a very nice gym where we can have the karate class.”

For karate to work you need the right environment, a dojo, a place dedicated to training the mind and body. There is no dojo in Deheishe so I too had to be creative and I created one in the gym at

El-Feneiq.

Using both my limited Arabic and some assistance I told the children that they need to remove their shoes and

socks before the lesson began. They did remove their shoes, but as children usually do they threw them all over the place. Then, rather than begin the class I asked them to come with me. I removed my shoes and placed them neatly against the wall. I told them that where my shoes go may seem like a trivial thing, but it creates an atmosphere of attention to detail and order, and that brings comfort and calm to the class.

“And keeping the dojo tidy is an important part of karate,” I added.

Once the shoes were in place, I assembled the children and proceeded to introduce myself and ask them their names and ages. Then I told them that the first thing we learn in karate is respect,

ihtiram.

In karate respect for others as well as for ourselves, is of the utmost importance. That is why we bow, listen to one another, use our heads and our words to resolve conflicts and solve problems. As I was saying this, I couldn’t help thinking of the irony in saying this to people who live under an occupying power that respects none of these things.

Then we began the lesson. As the children lined up I explained how to stand, and as I was explaining a girl who had practiced karate before called out the names of the different positions in Japanese. “

Musubi-dachi,”

she said softly, revealing that she knew the term for standing with our feet together. Then I showed them how to kneel down. “

Seiza,”

she said this time. She knew how to execute the moves and knew the commands of the various techniques in Japanese. It was good to have her there, and she was a great little helper for me and for the class. An hour had gone by quickly, but it was getting late in the day and dark outside, so I had to wrap things up. I promised we would start earlier the next day.

When I arrived the next afternoon, I saw a long row of neatly placed shoes in the corridor by the gym. More than 35 kids sat quietly on their knees in

seiza.

They were ready and they had taken in what I had previously taught them. The volunteers were visibly proud of the kids, and so was I. Half the class had been there the previous day and the other half was there for the first time. I welcomed all the new students, and I asked those who were there for the first lesson to share with the others what we had talked about.

“Never smoke, it gives you cancer,” was the first comment.

“Don’t hit others and avoid getting hit yourself,” was the next comment.

“Be respectful to yourself and people around you.”

“Do your best and do not give up when things get hard.”

On and on they went. I was in a daze. These little guys really internalized the lessons and were able to recall them accurately.

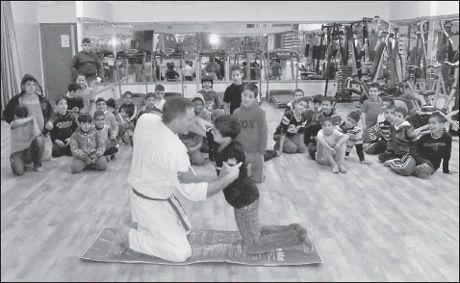

I noticed a pile of small exercise mats in a corner of the gym, and I knew exactly how we would end the class that day. There is nothing kids love more than to wrestle. I had them do lots of running and relays and then sat them down and explained how all fighting in karate is done, and wrestling especially. We begin with

ihtiram

—respect, which in karate is expressed by bowing before and after

each match. I made a point of demonstrating how even a student who is a lot smaller than I can take me down. I used Kusai, a particularly talented and serious 11-year-old who came to every session.

Karate wrestling in Deheishe.

“Knowing how to use your strength against a larger, seemingly stronger opponent is a big part of karate training,” I told them. This also applies when one is fighting to resist a larger and more powerful occupying power, and I made sure that this point did not get lost on the students and volunteers. While there is an aspect of karate that exhibits conformity, in reality, the history of karate is filled with defiance and rebellion. Karate is about beating the odds and developing an independent spirit. I wanted to share that sense of defiance with these kids. Not that they needed my help, because they could be plenty defiant on their own—but to help channel that energy and demonstrate that the relative normality in which they exist is in fact not normal, and that they should not be afraid to rebel in a responsible, non-violent manner.

When I was done teaching, Mazen picked me up and I returned to the Forum office. From there, Khaled drove me to his house in Beit Ummar, where I would be spending the next five days. Khaled, wearing a dark suit and a serious expression as always, had clearly not eaten all day, distracted by a million and one things. He drove through dirt roads and narrow alleys because most of the wide paved roads are off limits to Palestinians. I watched him as he absentmindedly sucked on one cigarette after another.

I have noticed that Khaled doesn’t just smoke his cigarettes. He chews on the filter for a while, and then inhales deeply like a man hungry for air. Then he blows out the smoke that has been thinned out because he’s absorbed so much of it. He chain smokes as though sucking in the freedom denied to him by the Israeli invasion into his life, his family, and his country.

Living in the West Bank among Palestinian friends, I began to realize that the Palestinians’ suffering goes on no matter how dedicated they are to peace and reconciliation. Dedication to reconciliation and willingness to reach out does not provide Palestinians immunity from the daily struggles with Israeli soldiers, the humiliation or the cold, discriminatory administration of Israel’s occupation regime. In Khaled’s case, if not for sheer luck or the grace of God, on November 13, 2004, he would have lost yet another family member to Israeli violence, his son Mu’ayed.

It happened two days after Yasser Arafat died. That was the day Arafat’s funeral took place in Ramallah, and smaller ceremonies and observances were held all over the West Bank for those who couldn’t make it to Ramallah. It was a solemn day for Palestinians and many others around the world. The Israeli army was supposed to keep a low profile and allow Palestinians to mourn the death of their leader.

But in Beit Ummar soldiers in an army Jeep decided to go screeching through town. Residents were leading a peaceful procession of mourning and a symbolic funeral, and as one may expect, the Jeep’s presence ignited the atmosphere. A few young people threw stones at the Jeep, and the soldiers responded by firing live ammunition. The result was two casualties: Jameel Omar, a 19-year-old student who was killed immediately, and Mu’ayed Abu Awad, Khaled’s 15-year-old son, who was shot by a 5.56 caliber bullet to the hip. Mu’ayed lay on the ground bleeding badly, and the soldiers stood around him, preventing an ambulance from evacuating him.

Khaled was in northern Israel at the time, in a room full of Israeli high school students. He and an Israeli member of the Bereaved Families Forum were there to speak about reconciliation. They explained that the cycle of violence has cost too many lives on both sides and must be stopped and that real dialogue should take place. Suddenly they were called outside the room and informed that soldiers had shot Mu’ayed.

The presentation ended abruptly, and as they turned to leave, Khaled stopped at the door. He turned to the students, who remained shocked in their seats.

“Whatever happens, even if the worst happens, even if I have lost my son, we must never lose hope. We must never stray from the path of reconciliation.”

Back in Beit Ummar, Mu’ayed looked like he would soon bleed to death, and his friends decided to evacuate him under fire. A few guys distracted the soldiers by hurling stones, and as the soldiers chased them, others managed to get Mu’ayed into the ambulance that took him to the hospital in Hebron, some 10 miles away. By the time he arrived his condition was too severe and the doctors in Hebron were not able to help him.

When word got out that Khaled’s son was injured, people at the office of the Bereaved Families Forum in Israel began searching for someone who could help save the boy’s life. In what turned out to be a joint Israeli-Palestinian effort, Mu’ayed was transported to an Israeli ambulance that took him to Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, where adequate facilities and the best-trained doctors could treat him. On the way, Israeli army medics tried to stabilize his condition, but by the time they reached the hospital his blood pressure was zero.

Mu’ayad was rushed into the operating room just as Khaled, breathless and sick with worry, arrived. At last, close to midnight, after long hours, the doctor came out of the operating room. “Had he arrived 10 minutes later, he would have died. Thank goodness, we were able to save him and save his leg.”

Many Israeli and Palestinian friends came to the hospital to be with Khaled and Mu’ayed during the difficult weeks of Mu’ayed’s recovery and rehabilitation. I called several times from the U.S. and spoke to Khaled, and I was relieved to hear that the worst was over.