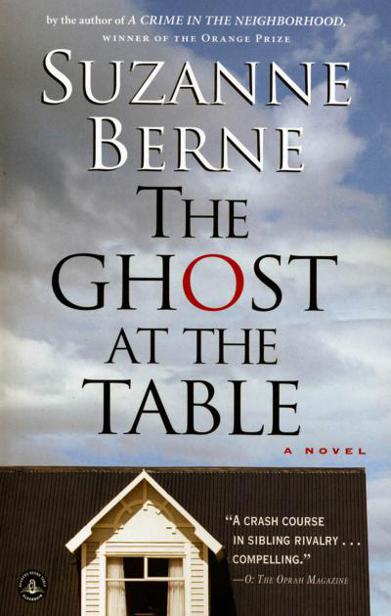

The Ghost at the Table: A Novel

Read The Ghost at the Table: A Novel Online

Authors: Suzanne Berne

G

HOST

at the

T

ABLE

a novel by

S

UZANNE

B

ERNE

A Shannon Ravenel Book

A

LGONQUIN

B

OOKS OF

C

HAPEL

H

ILL

F

OR

M

Y

D

ARLING

D

AUGHTERS

,

Avery and Louisa

The truth is, a person’s memory has no more sense than his conscience and no appreciation whatever of values and proportions.

M

ARK

T

WAIN

,

The Autobiography of Mark Twain

Going home for Thanksgiving wasn’t something I had planned on—or I should say, I hadn’t planned on going to Frances’s house in Concord, which over the years I’ve sometimes referred to as “home,” simply because it’s back east. But perhaps Frances heard me differently when I said “home,” perhaps she heard more than I meant to suggest. She is my older sister, after all, and there is that responsibility, often mixed with impatience, that older sisters feel toward their younger sisters, especially if those younger sisters have been, in one way or another, less fortunate than themselves. In any case, every year Frances asked me to come for Thanksgiving and Christmas, but every year for one reason or another, I said no. My visits to her usually happened in summer, when we were more likely to leave the house. Though of all the people in the world I probably love Frances best, after a day or so at home with her I found myself becoming lethargic and moody, leaving dishes in the sink, taking long naps in the afternoon. Meanwhile Frances’s normal good nature soon gave way to exasperation and apology. We both understood the effect we had on each other, only made worse by the holidays. Still Frances felt she needed to invite me, just as I needed to refuse. In this way, we absolved each other.

Or that’s how it worked until one October day, over a year ago now, when Frances called to say that our father would be spending Thanksgiving with her, for the first time in a quarter of a century, and she literally begged me to fly to Boston.

“Please, Cynnie,” she said on the phone. “It’s the first time in forever that we could all be together.”

All? I almost said. Our mother has been dead since I was thirteen. Soon after I was born she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which was later complicated by a heart ailment. Our older sister, Helen, died three years ago of lymphoma. Her funeral in Bennington had been the last time I’d seen my father, or Frances herself, for that matter. My father and his wife, Ilse, drove up to Vermont from the Cape, arriving just as the service began. The church was full of Helen’s patients and friends, several of whom spoke movingly of Helen, of her generosity and intelligence. Dad and Ilse stood at the back of the church wearing khakis and boat shoes, their hands in the pockets of their windbreakers. They refused to sit in the front pew with Frances and me, insisting that their legs felt stiff after the drive; then they skipped the burial and the gathering at Helen’s house afterward.

But in June my father had had a stroke, and now he was also getting divorced, at eighty-two, from Ilse, who was only in her fifties, but claimed that she couldn’t take care of him any longer. Frances had been making arrangements for him to enter a nursing home in a town near Concord. This was why he would be with her for Thanksgiving.

“Please come.” Frances lowered her voice. “It would really mean a lot to him.”

“Oh, I don’t think so,” I said.

“Please. Come for my sake, Cynnie. I don’t want any regrets and I’m sure you don’t, either.”

“I don’t have any regrets, at least not about him.”

But Frances wasn’t one to give up easily, especially when it came to finding a way to disguise some awkward angle or unsightly corner, which was perhaps why she’d succeeded so well as an interior decorator.

“Frankly,” she said, switching tactics, “I could use the moral support.”

“Moral support?”

“It might not be very easy with Dad, you know. A nursing home is a big change.”

When I didn’t say anything, she went on quietly, “And it’s a holiday. And Sarah will be coming home, her first time home since September, and I want it to be nice for her. So that’s a lot to manage, with Dad here, too.”

Sarah was Frances’s older daughter, a college freshman, who in the last couple years had become political. Sarah’s most recent cause, besides campaigning against the current administration, was “Doing Without.” People had too much stuff. Too much stuff was causing all the world’s problems. (Pollution. Nuclear proliferation. Sprawl.) I could tell Frances was afraid that if she didn’t make Sarah’s first homecoming a happy family occasion, Sarah might hold it against her somehow. She might believe that home itself was another thing that she could Do Without.

“But it’s only Thanksgiving Day that Dad will be at your house,” I pointed out to Frances. “Pick him up right before dinner and take him back right after. I’m sure the girls will help you. They’re old enough now. And Walter will.”

I could hear a distant ringing, like a call coming in on another line. Finally I had to say, “Won’t he?”

“Walter and I have been going through a rough time lately.”

“What kind of a rough time?”

“I can’t explain it on the phone.”

This was crafty. If there’s one universal covenant between sisters, it’s a primal interest in each other’s relationships. Frances and I had spent countless hours discussing the shortcomings of various

men in my life, few of whom she’d ever met; yet she understood them perfectly and found complexities in their faults, which made those faults seem pardonable, or at least interesting, though she would always assure me that I was “better off” whenever one of them disappeared.

“Are you all right?” I demanded.

“No, I’m fine. I’ll tell you about it when you get here. Will you come, Cynnie? Please?”

“Well,” I said at last, “I

have

been meaning to visit Hartford.”

“For your book?” she asked, too enthusiastically. “Is it done? I can’t wait to read it. We can drive down together while you’re here. To see Twain’s house, you mean?”

“But I was going to come east in July, after I’ve finished a draft.”

“Oh, not

July,

” Frances almost wailed. “It can’t wait that long.”

“What can’t wait?”

“

I

can’t wait,” she said. “To see you.”

T

HAT

N

IGHT

I C

ALLED

my friend Carita for advice: Should I go home, to Frances’s, for Thanksgiving, knowing that it might be a depressing visit, especially since my father would be there? Also, I wasn’t feeling my best right then. I’d recently broken up with a man I had been seeing for almost a year. He owned a bookstore, which was where I’d met him, and he was married, which I had known from the beginning, just as I’d known I was going to be unhappy with him even before we’d started sleeping together.

“Don’t go,” advised Carita. “Families are toxic.”

“But Frances says she needs me to be there.”

“Frances can cope.” Carita was washing dishes while she talked to me. I listened for a moment to the homely sound of clinking silverware and water splashing in the sink. Carita’s family lived in

Arizona, where her father built shopping malls; a portion of his income went to support an evangelical church that looked like a shopping mall. Carita herself was dark and wiry and flippant about almost everything. I pictured her warm untidy little kitchen, the string of red light-up chili peppers over the sink; the open spice jars; the refrigerator covered with magnets of dogs wearing kimonos, holding up photos of Carita and her girlfriend, Paula, on their trip to Hawaii and of their old, bad-tempered Yorkie, Prince Charles.

“I

could

visit Hartford while I’m there,” I said, “for the book.”

“Aren’t you originally from Hartford?”

“West Hartford.”

“Just say no,” she urged again. “Come over here for Thanksgiving. Paulie and I are cooking dinner.”

But by then I’d made up my mind to go to Concord and had only called Carita for the comfort of having someone try to argue me out of it.

“I wish I could,” I sighed, “but I guess blood is blood.”

“Blood,” observed Carita, “is bloody.”

C

ARITA AND

I

BOTH WORK

for a small company in Oakland that publishes a series of books for girls called Sisters of History, fictionalized accounts of famous women “as told” by one of their sisters. We focus on the childhoods, how one sister was marked from the start as unusual, special in some way, while the other was remarkable, too, but not

so

remarkable. Yet devoted. Always devoted. The books are meant to be cheerfully earnest feminist stories, emphasizing “the strong bonds between sisters” and illustrating the message that the most important things in life are human relationships.

Four of us do the research and writing. We find journals, memoirs,

letters, contemporary accounts that mention our subject’s sister and help create a persona for her. Then we make up what we can’t find or make up something to conceal what we do find, if it contradicts those “strong bonds.” On the company Web site we are described as “academic specialists in historical fiction,” though none of us majored in history in college; in fact, we were all English majors, like our editor, Don Morey, and he came up with Sisters of History in business school, after attending a lecture on marketing responsibly to children.

I cover literary women, which I consider the best category. Carita writes about famous women athletes. She refers to our books as “hysterical fiction for girls” and the “Lesser Lights Series,” mostly to needle Don when he starts talking about the social contribution we are making by producing books for girls that aren’t about teenage movie stars and diet fads. In interviews, he calls us the “Sisters Behind the Sisters of History.” Carita says he should call us the “Slaves of History,” but we’re paid pretty well, actually. Before Don hired me, I was teaching freshman composition courses at San Francisco State and proofreading for a magazine on exotic birds.

So far I had written books on Louisa May Alcott, Emily Dickinson, and Helen Keller, each from a sister’s perspective. Patriotically, we were beginning with American women. During one of my summer visits to Frances I toured Orchard House, the Alcott place, which is right in Concord, not far from Frances’s house. On another visit I borrowed her van and drove out to see the Dickinson home in Amherst. I never got to Tuscumbia, Alabama, to see the Keller homestead for

Witness to a Miracle,

the book I’d just finished. I felt the story suffered as a result. Context is everything when it comes to understanding a subject, and I like to include a blend of quoted detail and my own firsthand observations.

“Here in the parlor on Lexington Street,” I wrote in the preface to

The Little Alcotts,

“with ‘furniture very plain’ and ‘a good picture or two hung on the walls,’ it’s easy to imagine the March daughters darning socks and staring into the fire. But it is the Alcott girls we are with today, and Louisa and her youngest sister, May, are having an argument in a corner by the Chickering piano.”

May Alcott, Lavinia Dickinson, and Mildred Keller all turned out to be colorful (i.e., secretly resentful) reporters on their sisters’ lives, and I had a file drawer full of letters from little girls saying how much they’d loved my books, that it was as if I’d written about them and their own sisters. Don had slated me to write about Harriet Beecher Stowe and her sister Catharine for my next book. In her later years Stowe had lived next door to the family of Samuel Clemens, Mark Twain; I used to pass by both places whenever we took Farmington Avenue to and from the highway in Hartford. Ever since I was a girl, I’d always felt a modest connection to Mark Twain’s daughters. They’d grown up about a mile from my house, and there were three girls in their family, as there had been in mine. And throughout my childhood one corner of our living room had been occupied by a hideous old Estey player organ, inherited from my grandmother, which my father claimed had originally belonged to Mark Twain himself. Which is why when I turned in the Keller book I decided to ask Don if I could write about Mark Twain’s daughters instead of Harriet Beecher Stowe.