The Girl She Used to Be (13 page)

My elementary school days were lousy even

before

WITSEC. I remember sitting at lunch in first grade and no one would sit with me, like everyone already had friends and there

wasn’t any room for one more. Not that anyone really picked on me; they just acted as though I wasn’t there. My mom would

put little notes in my lunch, like, “I’m thinking of you, kiddo” or “I have a surprise for you when you get home” and stuff

like that. Those notes were the only thing that kept me from crying every day while I ate my bologna sandwich off in a corner

of the cafeteria. And the impossible thing to convey to the people assigning me a new life is that

that’s

what it’s like for me every day. It never changes. I just move on to the next place where I will once again not know anybody

and not feel accepted. I am still six years old, having never really learned how to make and keep friends or how to negotiate

in a relationship or even how to open up—because I’m

not allowed

to open up.

Two months ago, while I was showering, I slipped my hand under my breast and I was certain I felt a lump. I panicked. I got

out of the shower still covered in soap and reached for the phone. I needed a mother, a sister, a friend. Who was I supposed

to call, Farquar? There was no one.

No one

. I just stared at the phone and wept.

Sean can tell he’s lost me, takes in a breath like he’s going to ask another question or provide some great insight, but,

alas, it becomes a great exhale of nothingness.

“You know,” I say, watching as the young couple hops back into their car and speeds away, “I don’t even care anymore. Just

take me somewhere and dump me. No matter what place you take me to, I’ve been there before.”

Sean tries to get me to look at him, like all of a sudden he’s testing out a little compassion. I got news for him: He should

attend the class first.

I drift down in the seat, close my eyes, and feel the early pangs of a headache. “Point B, Sean. Just take me to point B.”

Night falls as we drive directly west. The sun and stars have no meaning when I’m on the road—that is, en route to my new

locale—because you can sit in the back of a car and eat junk food and do nothing equally over a twenty-four-hour period. Time

only matters once you have your hotel room and the television becomes your best friend.

It turns out point B is a small town in West Virginia, and though it feels like this is punishment for arguing with my protector,

I know Sean had nothing to do with the logistics of the operation.

Sean parks the car in the nearly abandoned parking lot of a skanky motel. He opens my door as I begin to collect my thoughts

and my belonging (that’s right, not

belongings

—all I have is that green sweater from Jonathan; for now, it’s enough). As I reach over the seat, I notice two Sudoku puzzle

books on top of my sweater. I slowly pick them up since I’m not sure they’re for me.

“Oh,” Sean says, “I bought those for you awhile back. Thought you might like some math puzzles to work on in your, uh, free

time.”

I smile as I get out. “That’s sweet.” That, of course, is all it is; Sudoku is as much about math as crossword puzzles are

about literature.

This time, as Sean walks me to my room, we do not speak. He opens the door to my contrarily luxurious suite, hands me the

key, mumbles something about seeing me in the morning. I close the door before he is finished.

If you blindfolded me, I could not tell you if I was sitting on the bed in a motel room in Arkansas or Kentucky or New Mexico

or West Virginia. The smell of the radiators, the squeaks of the mattresses, the sound of the couple arguing in the room to

the left and the sound of the snoring marshal in the room to the right, the feel of the worn blanket that has likely been

the canvas of a thousand sexual trysts and never washed, the frayed carpet under my bare feet, and the undeniable scent of

mildew tucked away in the far corners of the room—all the same.

I am tired of crying and I am tired of blaming and I am tired of Sean and what will end up being his cookie-cutter replacement.

I am tired of being force-fed my life.

I am tired of living, but what keeps me from dragging a blade across my wrist or diving off one of the crippled bridges that

cross the polluted rivers my motel rooms predictably border is the

idea

of life—that somehow, someday, I will figure a way to experience what it is like to live in unfettered happiness, to bask

in the freedom of security, and finally to understand the person I am supposed to be.

I am tired of… dreaming about it.

The digital clock on the nightstand reads 10:38

P.M.

and I can’t help but think the night is young. Somewhere.

I open the door to my motel room and walk away.

I

MEANDER TO THE ROAD THAT LED US TO THIS FORGOTTEN TOWN and walk as far to the side as possible. I walk for hours in one direction

and I can feel the dirt building on my feet as the road dust collects on my sandals. Miles later, signs of life emerge with

each step closer to West Virginia University. My journey ends at the fringe of the Monongahela River, where I climb up on

a bridge and stare at dozens of college students milling about the campus and the city of Morgantown. I wonder what has all

these kids so lively in these very early morning hours and I remember the season: final exams. If I hadn’t decided to take

this journey to another neverland, I’d be preparing my students for exactly the same.

A breeze washes over me and tugs at my hair and clothes; Jonathan’s gift prevents me from shivering.

Something lures me toward the campus. It is a hopeful place, an entity bearing the happy sentiments of kids getting educations

and starting careers and hanging degrees on their walls that bear their birth names. Instead of treading the collegiate sidewalks,

I opt to move toward a bar on the edge of the campus. I reach into my pocket and remove everything in it: two unused tissues,

a crumpled Post-it note reminding me to bring home the paperwork for the parent-teacher conferences that will be occurring

tomorrow, and the change from my last trip to Starbucks: sixteen dollars and twenty-one cents.

I gaze through the window of the bar and it seems the place is winding down. A few young couples are standing and reaching

for coats while the rest shoot pool and watch reruns of the day’s sports highlights on a handful of outdated televisions.

I walk in and glide to a stool at the bar, where I make myself comfortable under a bright Rolling Rock sign. The green light

on my pallid skin makes me look like I belong in a morgue.

The young girl behind the bar comes over and asks what she can get me, but her tone speaks of displeasure at having to start

another tab so near to closing. I assure her I will not be here long. She returns with a Budweiser draft, ordered because

it’s cheap—and can be easily nursed, if needed.

I scan the room curiously and it appears every element of the town is here: the college jocks; the good-looking-yet-slightly-effeminate

frat boys with their competing Greek letters; the townies—that is, the folks who probably once ruled this bar and refuse to

relinquish to the students; and the stragglers, the lonely people, like me, sitting idle and waiting for someone to tell them

to go be idle somewhere else.

What I don’t see is any sign of a hit man, but how can I not imagine that danger lurks most gravely for me no matter my locale,

that the Bovaros may already be aware of where I am, in this state, this town, this bar.

I turn back to my glass of beer and sip. As the brew delivers internal warmth, I realize why people become alcoholics; booze

is a true and responsive friend. I play with the condensation on the side of my glass as my stomach rumbles, and as I begin

to feel the slightest effect of the alcohol, my thoughts turn to Jonathan. I must be exhausted because I think puzzling and

inappropriate things, like the way his confidence is more substantial and intrinsic than any marshal I’ve known, the way his

body fills out his clothes, and what it might be like to kiss him. It isn’t long before these ideas evolve to issues of concern

for him. It occurs to me that, since he’s going to be returning home empty-handed, his life may be in danger.

Three college guys in their early twenties glance my way and smile. Then they whisper, then they smile, then they nod, then

they whisper, then they smile. Nothing good will come of this.

I return to thinking of Jonathan and the alcohol breaks my anxiety and fear and really allows me to open. I figure it’s not

only that Jonathan may be physically harmed by his tyrannical family, but that his feelings will be destroyed as well.

The college guys get a little louder and I assume that it’s a loss of inhibitions that brings one of them in my direction.

He keeps looking back at his friends and, based on how horrible I look and feel, and how dirty my hair and body are, there

is a wager involved.

Where’s a bag of Nacho Cheese Doritos when you need one?

He stands next to the bar for a few seconds, then slowly moves toward me. The way he keeps looking back at his friends—and

their reactive laughter—would certainly bring any girl to her knees.

Up until the very last seconds, I am preoccupied with thoughts of Jonathan, and I think I might need a second beer to sort

it all out. The bartender glances at me and I nod, and she quickly replaces my glass with another dollar draft. I drink, hard.

The college doofus—a real Tobey Maguire wanna-be, all short and small featured—stands right by my side and does not sit on

the available stool, which tells me he is ready for quick flight. This will not have a happy ending.

He offers me a napkin and a pen and says, “C-Can I have your autograph?”

I roll my eyes in his direction. “Sorry?”

“I was just wondering if I could get your autograph. I love your early work, especially ‘Rebel Yell’ and ‘Eyes Without a Face.’

”

His buddies laugh and somewhere deep inside I understand Jonathan’s proclivity for reactionary violence.

I consider a retaliatory remark but I really just want him to go away. Alas, no one knows more than I that the shortest distance

between two points is a straight line.

“Billy Idol,” I say, patting him gently on the shoulder. “It’s sort of funny, but since Billy is retro-cool, the humor attached

to your punch line is diminished, so it’s probably not something I would suggest you use again should you ever come across

a woman who weakly resembles the British rock star simply because she has short, stiff hair.

“Now, on to more important things. You have a serious character flaw, and I can say this with certainty based on the surety

of one or both of the following conclusions: One, you are viewed among your group as the weakest member, which is why you

were targeted and so easily cajoled into coming over here and harassing some person you do not know and will never see again;

or, two, you have a serious problem with insecurity and feel the need to prove yourself as a man to your buddies when you

know deep down that you will never reach the bar they’ve set—or that society has set—for how to act as a real man in this

demanding world. You may have some difficulty deciding which item it is, but I’m leaning toward both, with heavy emphasis

on item two. You may be unsure of my comments right now, but they will be hammered home one day soon when you are with your

girlfriend or wife and you are trying desperately to fulfill your sexual promise to your beloved—but your body will sputter

and smoke and be unable to deliver the goods. You will, indeed, be amazed that you cannot produce the simple biological reaction

that pretty much every other living, breathing man on this planet can produce within a few seconds of seeing his lover’s naked

body. No, you, my dear friend, will stand there or sit there or lie there as limp as a horse’s tail, and I am sorry to say

that you will remember my face and you will remember this conversation, and the truth, the essence of your very life, will

come into focus and blind you in a permanent way as five simple words echo throughout your brain for the rest of your life:

I am not a man

.”

My college friend stands with his mouth open and hands at his sides. It seems he’s about twenty or so words behind. When he

finally catches up, he glances at his buddies, who are no longer laughing. He turns back to me and asks, “Are you a philosophy

professor?”

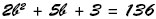

I chug a third of my beer, burp under my breath, and answer, “Worse. I teach math, which means I’m all about

certainty

, Noodle-boy.”

I drop five bucks on the bar, walk toward the door, and wink at the other two college guys while whistling the tune to “White

Wedding.” As I walk down the street, I glance back through the window and see the kid still standing at the bar, head down,

hands in his pockets. His friends do not rise from their seats.

My point has already been proven.

The unexpected clarifying effect of the alcohol along with the fresh air brings everything to the edge of my mind and I try

to seize the moment. I have no idea where I’m heading, but I’m in no shape to continue walking. I am ready to burn out. I

have just over ten bucks on me and I am in desperate need of a shower and my feet and body are aching and I have nowhere to

go and I think, “This is how you become homeless,” and I’m saddened that the streets I may have to live on are in wild, wonderful

West Virginia, that of all places to

end

, it is going to be here.