The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (103 page)

Read The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 Online

Authors: Robert Middlekauff

Tags: #History, #Military, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies)

the rebels survived, despite their defeats at Charleston and Camden, because they were succored by their friends in North Carolina and Virginia. What he could not see was that the basis for rebellion existed in South Carolina independent of support to the north. Nor could he ever quite grasp that the British army, by its presence, nourished the rebellion it had been ordered to suppress.

Greene did not worry when he learned early in January that Tarleton, who had been about twenty-five miles west of Cornwallis at Winnsboro, had set out after Morgan. Greene had reached the new camp at Cheraw on the Pee Dee the day after Christmas. By that time Morgan was nearing a position from which he could threaten the western posts of the British.

Early in the new year Tarleton proposed to Cornwallis that they attempt to trap Morgan between them somewhere near King's Mountain. Cornwallis agreed and freed Tarleton for the chase but held up his own pursuit until he was able to learn whether the rumor that the French were at Cape Fear had any substance. It had none, and the dispositions of British troops seemed favorable to a new expedition to the north -- Benedict Arnold, who had defected to the British the preceding September, had led a raiding expedition to Virginia, and Major General Alexander Leslie, who had sailed from New York in October with 2500 reinforcements, reached Camden on January 4, 1781.

24

While Cornwallis crawled a few miles out of Winnsboro, Tarleton and Morgan played hound and hare across the South Carolina backcountry. Morgan moved on January 16 from Burr's Mills on Thicketty Creek to Hannah's Cowpens, a distance of twelve miles. He was seven miles from Cherokee Ford on the Broad River. The day before Tarleton had made it across the Pacolet at Easterwood Shoals, only six miles below where Morgan had posted his troops. Tarleton had traveled light; Morgan had pulled heavy wagons. Now with Tarleton pressing him, Morgan decided that he must fight; if he fled he was certain to be overtaken, perhaps at the fords or just over them, both places less favorable to the defense than the Cowpens.

25

Daniel Morgan spent much of the night of January 16 with his men. He resembled his men in many ways. He was older than most, of course, but he spoke their language, a direct rough talk that has always appealed to soldiers.

Moving among the campfires, Morgan may have revealed

____________________

24 | Willcox, |

25 | Ward, II, 755. |

something of his plan, certainly he revealed his confidence in his troops and himself. A more practiced tactician who knew the textbook doctrine on the deployment of troops would not have chosen Hannah's Cowpens because of what it offered the defense. According to eighteenth-century conventions, the Cowpens offered nothing -- except maybe an opportunity to the attacker to envelop the defender. The Cowpens was a meadow of about 500 yards in length and almost as wide. About 300 yards from its southern edge a low hill rose, and behind it seventy or eighty yards, a second, lower, hill stood. There was little undergrowth but there were pine, oak, and hickory trees scattered over the meadow. The place was made for cavalry -- and Tarleton had three times the number of cavalry available to Morgan. As the British general Charles Stedman, who inspected the field not long afterward, said, the ground was not well chosen for Morgan's purposes -- his flanks were open, he was vulnerable to cavalry, and the Broad River behind his back made retreat impossible. Morgan later stated that he had chosen the Cowpens because its defects would leave his militia no choice save fighting. They all knew what had happened to Buford's men at Waxhaws when they tried to run away.

26

Whatever his reasons for choosing Cowpens, Morgan used the terrain well. Sometime before daybreak a scout brought word that Tarleton was on the move and only about five miles away. Tarleton had roused his troops at 3:00 A.M. and set out as rapidly as possible. Morgan's men then crawled from their blankets, ate breakfast, and took their places.

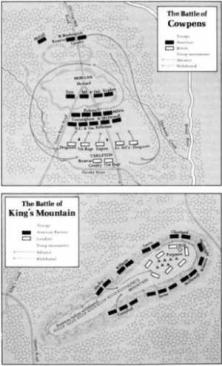

The main line, composed of Maryland and Delaware regulars at the center and Virginia and Georgia militia at the ends, ran across the higher of the two hills. Altogether about 450 men made up this position. Some 150 yards to their front about 300 militia from the two Carolinas spread out for approximately 300 yards. In front of them, 150 riflemen from Georgia and North Carolina crouched behind trees forming a line of skirmishers. Morgan did not have many men in reserve, but they were well chosen, eighty cavalry of Colonel William Washington and forty-five mounted infantry from Georgia, all posted out of sight behind the second hill.

Tarleton's force included his legion, a little over 500 cavalry and infantry; a battalion each from the Royal Fusiliers (the 7th) and the High-

____________________

26 | Ibid., |

landers (the 71st); and smaller contingents of the 17th Light Dragoons, royal artillery, and Tory militia. In all he had about 1100 men and outnumbered Morgan slightly. This army marched into the Cowpens after daybreak and was quickly deployed in a line with dragoons on either end, the Royal Fusiliers, the legion infantry, and the light infantry in between. Two hundred cavalry and the Highlanders were held in reserve. The royal artillery -- two "grasshoppers," three-pounders mounted on long legs (not wheels), hence the name -- were placed with troops on the front.

This line had barely formed when Tarleton sent it forward. By this time the skirmishers in advance of the American position had already done their work, cutting down the fifteen horsemen Tarleton had ordered to advance when he first entered the Cowpens. The American militia of the second line, commanded by Andrew Pickens, awaited the British patiently, knowing exactly what their leaders expected of them. Morgan had not asked that they defend their position until death, but only that they give two effective volleys and then pull back behind the hill where they would be formed once more. They fulfilled their assignment carefully, saving their first volley until Tarleton's men came into range. They then fired, reloaded, fired again, and pulled back to the left flank of the main line. Not all made it unmolested. The British charge, though not a model of order, moved fast enough to intercept the Americans on the far right who had to cut across the entire line of battle. Before all the American militia could make it, the dragoons were among them swinging sabers and firing pistols. At just the right moment Morgan sent Washington's horsemen to the rescue. The appearance of the American cavalry surprised the dragoons and in a few minutes they retired.

The main line had continued its attack. It had taken heavy casualties from the fire of Pickens's men, but it was intact and still on the move. The British now received an unpleasant shock -- the line of Continentals and Virginia militia along the hill did not retreat. Instead they delivered fire that threatened to disintegrate the assault.

Tarleton then did the only thing he could do -- he called on the Highlanders in reserve. The Highlanders, with several hundred yards to cover, made for the American right. General John Eager Howard, in command of the American main line, watched them come with considerable concern. He noticed that the Highlanders extended well beyond the American right flank, and should they persist, would wrap themselves around that end of his line. Anticipating this flanking movement, Howard ordered the company on the far right to face about and wheel to the

left, a complicated movement on the parade ground and much too demanding for militia to execute while under fire. Understandably confused, the militia company faced about and began to retire to the rear of the hill. There is nothing more contagious in battle than a move to the rear (except perhaps flight in panic), and the rest of the line also began to fall back. Surprised at what he saw, Morgan asked Howard what this line was doing and whether a retreat was in progress. Howard had the wit to see that the men were in control of themselves -- and were far from panic. Upon receiving this reassurance, Morgan pulled back himself to find a place for a stand.

Tarleton's men had also seen the American right give way and convinced that a rout was in prospect broke their formation -- it was already in some disorder -- in order to close with the enemy that had killed so many of their comrades. This wild rush also deceived Tarleton, who, thinking to capitalize on a familiar circumstance -- American panic -called up his reserve. By this time most of the Americans had reached the reverse slope of the hill and were hidden from British eyes. Whereupon Howard and Morgan ordered them to turn around and shoot into the British mob that now came over the crest of the hill about fifty yards away. The British who plunged into this fire gave way to wild fear almost immediately as their ranks crumbled. Then they were struck on their flank by Washington's cavalry which had once more ridden from concealment behind the second hill. Pickens's militia now made their second appearance of the day following behind Washington's horses and Howard's infantry. In a few minutes the Americans had won the battle, though the Highlanders, retaining at least a partial integrity as a unit, fought with particular bravery, as did the small crews that served the grasshoppers.

Courage frequently mastered the deficiencies of leadership in the Revolution, but in this case it had no chance. The Highlanders were either killed or surrendered, and the artillerymen died gallantly trying to hold their howitzers. Beaten, the British soon began to beg for quarter. Tarleton escaped with forty horsemen. He left behind 100 dead, over 800 of his men prisoners (229 with wounds), the colors of the 7th Regiment, the two grasshoppers, 800 muskets, and most of his baggage, horses, and ammunition.

27

____________________

27 | I have reconstructed the dispositions of troops and the action of the battle from the following: |

Tarleton never realized what had happened to his command at Cowpens and publicly at least did not admit that he had made serious mistakes there. He confessed that the fire from Howard's retreating line had been "unexpected" and had produced "confusion" among his soldiers. The panic that followed baffled him, however. In refighting the battle, a luxury that the vanquished relish in a perverse way as much as the victor, he ascribed a part of the defeat to the cavalry's failure to form on the right and presumably to attack there. He also -- in a very confused series of comments -- remarked on the "extreme extension of the files," characteristic he thought of the "loose manner of forming which had always been practiced by the king's troops in America."

28

Loose was a well-chosen word but surely too narrowly applied by Tarleton. He had rushed into the battle, as Charles Stedman later implied, with the daring of a partisan captain heedless of the circumstances of his army and the enemy's. The attack began even before his line had formed and with his reserve, the 71st Regiment, still struggling to come forward through thick underbrush almost a mile behind. The attack appeared to Roderick Mackenzie, a young lieutenant wounded on the field, "premature, confused, and irregular." Yet at one critical moment, it might have succeeded, when the right side of the American main line began pulling back, had Tarleton been able to pour his reserve against that side. Instead, the British, irresolute and disorganized, delayed, and Howard's men re-formed themselves into an effective line.

29