The Good and Evil Serpent (59 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

There is no reason to doubt that Philo of Byblos depicts Zoroaster as a serpent god. He includes this excerpt in his section on serpents, and prior to this excerpt refers to the “snake with the form of a hawk.”

302

It is interesting to observe and ponder why centuries earlier the artisans who constructed the mask for Tutankhamen placed above his eyes the hawk and the serpent.

An Elamite seal impression of circa 1600

BCE

depicts the Elamite serpent god seated on a snake and above a column of two entwined snakes.

303

This is reminiscent of the bronze column showing a serpent with three heads at Delphi. According to Herodotus

(Hist

. 9.81), the column commemorated the defeat of the Persians in 479

BCE

. Constantine moved the snake column to Constantinople; it was unearthed in 1855 and what remains of the masterpiece can be seen today in Istanbul.

304

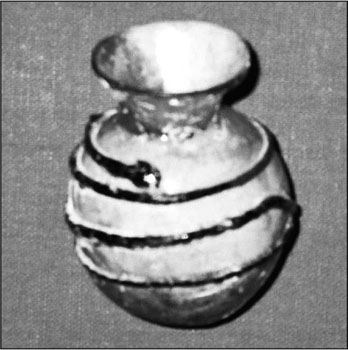

Figure 71

. Byzantine Glass Appliqued with Serpent with Prominent Head. Found in or near Jerusalem. JHC

Hezekiah destroyed the Nechushtan. Most likely this name represented a huge image of a serpent in the Jerusalem Temple (2 Kgs 18). Those who worshipped this serpent image could appeal to the tradition that Moses had created it, or one like it. And Moses had followed God’s command, according to the ancient traditions (Num 21).

305

According to the

Acts of Philip

, Bartholomew and John suffer hardships because of much wickedness from those “who worship the viper, the mother of snakes” (8:94). The ways a snake may symbolize the divinity are thus not only varied and complex but also transcultural, even when we allow that in the Levant there was much shared symbolism.

Unity (Oneness)

No other animal is as streamlined as the snake. It is simple and sleek. The ancients perceived it as the quintessential symbol of unity or the symbol one. Thus, the limbless snake in its sheer simplicity represents unity and completeness. It can also, because of its lack of appendages, symbolize one (cf. 2.5). This aspect of serpent symbology is best represented by the Ouroboros that sometimes has inside it a Greek inscription that means “all (is) one.”

The bronze, silver, and gold bracelets, earrings, and rings complete a circle (

Figs. 34

,

35

,

38

–

40

). Such serpent jewelry can represent more than apotropaic power.

306

They symbolize also unity or the symbol one.

Ancestor Worship

The snake often lives deep in the earth where the ancestors are buried (cf. 2.14, 2.18, 2.24); hence, the serpent came to symbolize ancestor worship. In Hastings’ classic

Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics

, MacCulloch offered the opinion that ancestor worship was a dimension of the ancient serpent cult “in so far as certain snakes haunting houses or graves were associated with the dead.”

307

Snakes are sometimes perceived as an embodiment of one who has died. Seeing snakes living near or in graves and tombs stimulated the imagination of the ancients. Perhaps such belief was enhanced if one, descending into a burial chamber, especially in or near Jerusalem in antiquity, notably during the Iron Age, approached a body that had lost its flesh and saw a snake slither away into the darkness.

In the Greek world, the snake could be a personification of the grave and bearer of the soul of the dead.

308

As W. Burkert states, the Greeks believed not only that “the deceased may appear in the form of a snake;” they also thought that “the spinal cord of the corpse” could be “transformed into a snake.”

309

Plutarch, Ovid, and Pliny the Elder record the folk belief that the marrow of the dead could metamorphose into a snake.

310

Earth-Lover

The snake must receive its warmth from the sun or the earth; hence, it is often associated with the earth and perceived as the Earth-Lover (cf. 2.12). In Babylon, the serpent is the offspring of Ka-di, the earth goddess. Küster devotes a full chapter to the serpent as the spirit of the earth

(Erdgeist)

. This seems especially appropriate for legends and myths associated with Cybele, Cerberus, the Giants, Hydra,

311

Tryphon, and others.

312

Serpent symbolism is associated with the earth deities, like Demeter, Hecate, and Kore. In some myths, Asclepius was imagined to have originally been an earth god. According to the Hermetica, when Isis instructs Horus, we hear that “snakes and all creeping things love

and all creeping things love earth

earth .”

.”

313

Chthonic

The snake can disappear into the earth (cf. 2.18), lives in caves beneath the earth, frequents graves, and hibernates within the deep recesses of the earth for months (cf. 2.24).

314

Thus, the serpent is the primal symbol of the chthonic world.

315

Such iconography and symbology appear in neo-Assyrian and neo-Babylonian art and in the Egyptian Coffin Texts.

316

The numerous images of three chthonic gods standing on a serpent are a significant indication of the Egyptian perception of the serpent as a symbol of the underworld.

317

One can easily comprehend why Egli, in his book on serpent symbolism, emphasized that the serpent was the symbol of the underworld.

318

In

Mythologies of the Ancient World

, S. N. Kramer points out that the serpent was customarily perceived as “the primary ‘body’ of any autoch-thonic deity in historical times.”

319

Ancient Hittite mythology involved tales that served cultic needs. Perhaps the best known of these myths entails the fight between the Storm-god and the Dragon who is called

illu-yanka

. This is both the proper name of the monster and the common noun for “dragon” or “serpent.”

320

Long before the Greeks and Romans, Assyrians and Egyptians, as well as others, observed the snake and accorded it mysterious chthonic knowledge. In

The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Egypt

, M. Lurker succinctly and accurately accesses this dimension of serpent symbolism:

As a chthonic animal the snake was one of the life-creating powers, for example, the four female members of the Ogdoad bore snake heads and Amun appeared as a primeval deity in the form of he serpent Kematef. When the corn [= wheat]

321

was brought in and wine was pressed, an offering was made to the harvest goddess, Thermuthis, who was serpentine in form or was depicted as a woman with a serpent’s head. Furthermore, the demons of time and certain divisions of time were in the same form; the two-headed snake Nehebkau appears in the book of the netherworld, Amduat, and the attendant vignettes.

322

Critical studies on hieroglyphics stress that Amun is symbolized in a serpent’s body.

323

When we discussed the Minoan serpent goddesses or priestesses we suggested that these images denoted chthonic power. Perhaps some Minoans saw in such images a way to control earthquakes and certainly to stimulate the fertility of the earth (

Fig. 28

). A. Evans offered his erudite opinion that the Minoan snake goddesses or priestesses signified “apparently the Underworld form of the great Minoan Goddesses.”

324

As A. Golan states in

Myth and Symbol:

“The serpent was the preferred incarnation of the deified lord of the lower world.”

325

Küster arrived at the conclusion that, for the Greeks, the major characteristic of the serpent is its chthonic character. Serpents were “chthonic gods” (x86voi

8EOI)

.

326

We have seen funeral dedicatory reliefs that suggest that the serpent is chthonic. Asclepius and his companion snake were also considered to be chthonian. The dream of devotees of Asclepius, when they learned that an illness was fatal, could be comforted by the thought that Asclepius was chthonic. He controlled the next world; moreover, Asclepius had the power of resuscitation.

Magic

The snake is open-eyed (cf. 2.4) and elusive (cf. 2.6), can live for very long periods without food (cf. 2.10), can be almost imperceptible (cf. 2.13), and appears to have magical knowledge (cf. 2.16 and 2.17). These physiological characteristics and mysterious habits of the snake made it a symbol of magic. It appeared and disappeared without sound or warning. It can move through grass almost unperceived; the leaves do not even move.

327

In antiquity, the serpent’s ability to move and climb became proverbial; for example, note the following imagery in twelfth-century

BCE

Assyria: “Like a viper on the rugged mountain ledges, I climbed dexterously”

(Annals of Tiglath-pileser I

2.76–77).

The Ugaritic snakebite incantations use paronomasia (a play on words) to cause the desired magic.

328

MacCulloch surmises that the armlet or charm and other serpent iconography from the Paleolithic Period “might have been for some such magical rite as that of the Arunta.”

329

The hand of the god Sabazius is often shown holding a pinecone and animals, especially a snake. The depiction reflects some form of magic, since the pinecone, frog, lizard, and snake were imagined to possess magical powers.

330

In

Oneirokritica

4.67, Artemidoros tells of a dream in which a woman sees herself giving birth to a snake who becomes a mantis.