The Great Agony & Pure Laughter of the Gods

Read The Great Agony & Pure Laughter of the Gods Online

Authors: Jamala Safari

Tags: #The Great Agony and Pure Laughter of the Gods

The Great Agony and Pure Laughter of the Gods

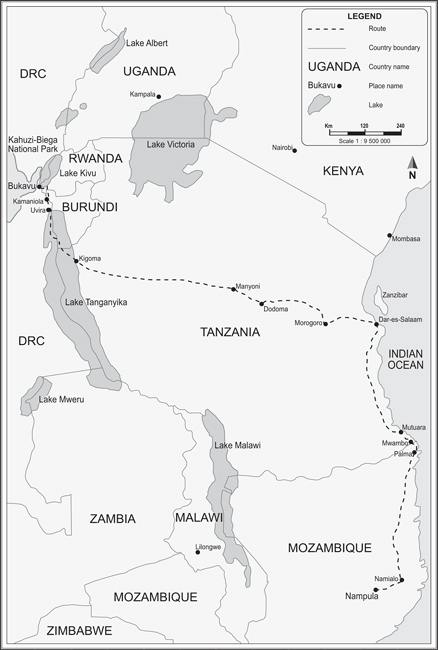

RISTO’S JOURNEY

JAMALA SAFARI

B

Y THE SAME AUTHOR:

Tam Tam Sings

(Poetry, 2008)

Published in 2012 by Umuzi

an imprint of Random House Struik (Pty) Ltd

Company Reg No 1966/003153/07

First Floor, Wembley Square, Solan Road, Cape Town, 8001, South Africa

PO Box 1144, Cape Town, 8000, South Africa

© 2012 Jamala Safari

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or be stored in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

First edition, first printing 2012

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

ISBN

978-1-4152-0176-3 (Print)

ISBN

978-1-4152-0478-8 (ePub)

ISBN

978-1-4152-0479-5 (

PDF

)

Cover design by publicide

Text design by Chérie Collins

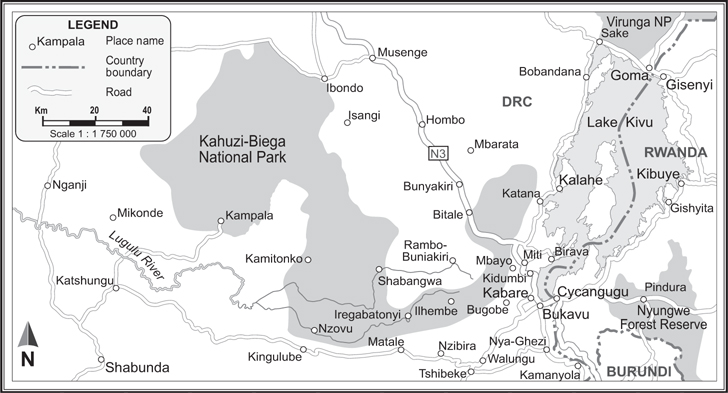

Maps by Rudi de Lange

Set in 11.5 on 15 pt Granjon

To Willy Mwana-wa-Bene Kagayo and all child soldiers in the world

KAHUZI-BIEGA NATIONAL PARK AND SURROUNDING AREAS

. Foreword .

Thousands or more? No one knows how many exactly. Among them, Sudanese, Colombian, Rwandan, Burmese, Sri Lankan, Congolese … The list includes at least thirty countries. At times willingly, but most of the time abducted or forcibly recruited, child combatants are fighting for government armies, opposition forces, militias and paramilitaries in their countries or neighbouring ones.

The story of Risto is emblematic of many other abruptly interrupted childhoods. It embodies one story in particular, one that has left a scar on Jamala Safari’s life. Jamala (originally from the town of Bukavu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and his family still await the return of their cousin. Theirs is a constant vigil, mourning with no closure. They have lived in hope and desperation, with unspoken dreams and terrors, ever since that day in 1996 when Safari’s cousin, William Mwana-wa-Bene Kagayo (literally ‘William Child of Others’ in Mashi dialect), disappeared.

Almost fulfilling the prophecy of his name, the boy refused to leave town when the warning came to evacuate. Soon afterwards he became one of the first child soldiers (known as ‘kadogo’ in the

DRC

) to join the rebel movement of Laurent Desiré Kabila, which later took over the country. Further than that, nothing is known of his fate.

Recounting the intricate psychology of a child combatant, torn between innocence and damnation, the loneliness among others in the same hell, the survival mechanisms, the challenges of rehabilitation and reintegration, Safari takes us into the land of desolation that is the lot of child soldiers.

Never found. Never buried. This book honours their memory, and especially William Mwana-wa-Bene Kagayo, whether he is walking somewhere in the lush forests of the Kivu, or whether the red earth of the region has already claimed back the blood of its child.

Refugee rights activist, researcher and humanitarian worker in refugee operations.

April 2012

Sometimes Risto’s father would say that man is the forger of his own history. In his hands lies the power to challenge and to change, in his feet, the conquering force, and in his mind, the driving compass. Therein is the essence of miracle and mystery. Good or bad, it will be the legacy left behind when he no longer has a voice to speak or strength to stand.

Many times Risto wished not to walk, not to touch; to stand still or find a cave to hide in. Then no footstep would be seen and his hands would leave no mark behind. If only that cave could be found, he would be in there right now; he would get in, close his eyes, clog up his ears, and ask rat and mouse to fill up the hole with soil. Then he would leave this earth, and sleep and sleep forever … and peace would come to his spirit and soul. Sometimes he wanted touching, walking, but was afraid to put his foot down in the flooding river, in the stormy fire, in the ghostly mouth of the world.

In the end, he found himself on a fragile island: north, east, west, south, no path. All around him, children like him, raped and killed, many with hacked-off hands and legs, the young mutilated. And the war continued. Each day, moaning came from nearby.

Sometimes three or four would die in his street alone. He would hear people yelling, screaming at the announcement of death. Always the same, the story the same:

They entered our house, we wanted to give them money, but they said they didn’t need le francs Congolais. Finally they locked us in a room. They took Mama and our sister in one room and Papa in another one. We heard Mama and our sister yelling and yelling, like birds whose feathers are being pulled out while alive. Later, it was cold silence. We heard a few shots. There was no sound in the house after the door was slammed. Half an hour later, when the neighbours came and opened the door for us, we were already orphans and without a sister. Papa was shot in his forehead. The neighbours didn’t want us to glance at Mama and our sister. Their bodies were naked, blood spots were coming up north from their navels. Both of them dead.

Children went on playing. They were told never to go far from home because anything could happen, and their family might need to flee the town. They might hear something like a thunderclap, then a heavy hail-fall on the roofs. Then a big cloud of smoke in the sky, meaning a bomb had fallen on nearby houses. People would moan, weep, but no mercy would come their way. Guns and death had become part of their daily lives. That was how they lived.

This was Risto’s hometown, Bukavu, where he lived, tried to dream, then refused to, as he knew there was no place his foot could walk to write his own history. Risto Mahuno, fifteen years old, with eyes older than his age. He had seen more than he deserved.

One could say that soccer brought healing to Risto. This was the only time his mind forgot his wish of finding a little cave where he could sleep forever in peace. Meeting his friends every day to play football, he felt the need to live again. No one remembered anxiety or felt fear when they played. They forgot their pain and time went on quietly. They played the way they used to play when Bukavu was still peaceful, with its green trees, children running up and down its streets like lost baby goats, and the taxi drivers driving twenty-four hours a day … in those days, one would have thought that if the world was Paradise, Bukavu would be its capital city. That was just a few years ago, just yesterday.

It was a beautiful day in Bukavu. Soccer fever had infected the boys and they played the game under a hot sun. The sweat dripped off their faces into the dust. Then a frizzing silence consumed time, seconds became hours.

Something has happened, thought Risto, lying on the ground.

A great noise came from all directions. He heard women screaming and yelling, calling and searching. He was lost, confused between his memory and the reality he saw around him. Then he felt a little clearer, and he looked all around the open field where they had been playing. There was no goalkeeper, nor defender, nor striker; none of them were playing anymore.

Where he lay, Risto’s ears heard a lingering noise like bee songs. He could see the goal posts. The goal stood empty. Ombeni the goalkeeper wasn’t the real Ombeni who had been there a few minutes ago. He was in pieces. The scene was a butchery. Head and chest were apart, a hand here, a leg there, this here, that there. Risto’s nostrils were too small for his breath. His body shook.

Their goalposts were covered in thick smoke, a house was burning, the nearby kitchen was on fire. There was no sign of Frank, Ombeni’s older brother, only a hole two metres from the goal. It was the size of a palm tree.

‘Come, come, come Risto,’ a woman’s voice called. It was his mother. ‘Are you okay? Are you all right?’ she kept asking. She shook too, but her voice was soothing.

‘I am fine, Mama.’ His body had no wound.

‘Are you okay, my son?’ she persisted, lifting him up onto her back like a precious golden basket. Risto did not like to be held like a baby on his mother’s back, but there was no choice. A fifteen-year-old boy had become a little child. He wanted to walk, but his entire body trembled like a rootless tree hit by a rhino.

More and more people came to pick up their children, the wounded and the dead, to extinguish the fire; more noise followed. Some cried for the dead; others, especially children, were seized by fear, others were calling their relatives’ names. It was chaotic, like being in an open-air market consumed by fire. The running, shouting, screaming …

The night passed. The story had grown, moving from the eyes of children on a playground to

TV

screens around the world. The news became a song. On the streets, it was a greeting for men, women, old and young people. At local radio stations, the news was repeated like a refrain, coming and going every thirty minutes.

‘… Yesterday at about 2:30pm, a bomb that appears to have come from over the Ruzizi River on the Rwandan side exploded on a football field in Bukavu. Two young boys were killed and three are seriously injured …’

The story hung in the air, coming back like a hiccup.