The Great Big Book of Horrible Things: The Definitive Chronicle of History's 100 Worst Atrocities (73 page)

Authors: Matthew White

The increase in the use of machinery took its toll. During the American Civil War, U.S. Army personnel suffered one accidental death for every eleven deaths in battle. By World War II, that was up to one accidental death for every four battle deaths.

37

Soldiers were now being crushed in jeeps, smashed in airplanes, burned in trucks, scalded and poisoned by strange new chemicals, mangled and electrocuted by heavy equipment, and blown apart by mishandling heavy munitions.

World War II produced the first naval battles in history in which the opposing fleets never laid eyes on one another. Instead of cannons, it was radar-directed fighter planes that delivered the killing blows between ships across miles of empty ocean.

The experience of World War II reinforced the truism that war sparks technological innovation. Radar, jet aircraft, computers, sonar, antibiotics, and guided missiles were some of the new technologies first deployed in World War II. Secret labs all over the world—American nuclear physicists at Los Alamos, British code-breakers at Bletchley Park, German rocket scientists at Peenemunde—helped determine the outcome of the war.

On the other hand, we can go too far in focusing on the technology. Only the American army came close to fighting a completely mechanized war. Aside from specialized Panzer divisions, the Wehrmacht still slogged through the mud with horses pulling their artillery pieces and supplies. Even the cold industrial efficiency of the death camps can be overstated. Most victims of the Holocaust died in ways that have worked for centuries—disease, overwork, hunger, and face-to-face massacres.

Aside from the occasional breakthroughs achieved by armored thrusts, most armies fought much as they had during the First World War—with riflemen digging in or attacking and machine gunners defending under cover of artillery. On the Russian front, where most of the fighting happened, field artillery firing by map coordinates into targets out of sight did more killing than other weapons. The artillery expended 80 percent of the total ammunition fired and caused 45 percent of deaths in battle. Examination of the dead and wounded showed that heavy infantry weapons (machine guns, mortars, and light artillery aimed by sight) killed another 35 percent. Aircraft caused 5 percent of battle deaths; armored vehicles killed another 5 percent. The light infantry weapons that are the staple of war movies (rifles, pistols, grenades) were essentially for self-defense; these inflicted 10 percent of battle deaths.

38

Air Power

Airplanes became major agents of destruction during World War II. Precision bombing of military and industrial targets was the most effective use of aircraft, and it was completely legal under the international laws of war. This, however, required a better-than-average mix of intelligence, reconnaissance, and bomber design. It also required bombers to approach on a straight path in clear daylight directly into a curtain of antiaircraft fire and swarms of defensive fighter planes.

Because of these difficulties, air forces were tempted into the indiscriminant destruction of softer targets. Early in the war, cities were attacked with a random scattering of bombs to terrify the inhabitants, but as the size of air forces increased, so did the body counts. The German bombing of Rotterdam on May 14, 1940, which killed around 850 civilians, horrified the world.

39

A year later, on April 6, 1941, the first German air raid against Belgrade killed 17,000 civilians.

40

The opening air raid against Stalingrad killed 40,000 civilians on August 23, 1942.

41

Soon the annihilation of cities became a science. Over the course of a night, as many as a thousand planes would be sent against a target. The first waves of bombers would drop explosives all over the city to splinter wood buildings into kindling, followed by later waves that scattered incendiaries to start little fires. Soon, the various fires consolidated into one gigantic firestorm, which created its own weather system with hurricane winds and a heat so intense that it warped metal, cracked masonry, and carbonized bodies. A firestorm could sweep a city clean off the face of the earth and suck the oxygen out of underground shelters, suffocating all of the people who thought they were safe. The British launched the war’s first major firebombing on the night of July 28–29, 1943, against Hamburg, incinerating 42,000 residents.

42

On the night of February 13–14, 1945, Allied bombers destroyed Dresden and 35,000 civilians.

*

On March 9–10, 1945, American bombers destroyed Tokyo, killing 84,000 inhabitants.

43

Since the beginning of the war, physicists all over the world had been reporting to their governments that splitting radioactive atoms would release a massive pulse of energy that could be used to obliterate entire armies with the flick of a switch—so God help us if the enemy gets this first. Secret research programs were established in Germany, America, Russia, and Japan to explore this potential. As the world’s primary industrial power, the United States was the first to work out all of the technical problems. On August 6, 1945, a single airplane dropped a single atomic bomb on Japan, and the city of Hiroshima was blasted out of existence, taking along 120,000 of its inhabitants.

44

Three days later, another nuclear strike destroyed Nagasaki and 49,000 of its inhabitants.

45

Because the war was almost over anyway and the bombs were used against cities rather than armies or fleets, debate rages over whether these attacks were necessary; however, two other facts stand out. The Japanese stopped their dithering and surrendered unconditionally a few days after the bombing of Nagasaki, and since that time, nations armed with nuclear weapons have carefully avoided fighting big wars with each other.

Aftershocks

The fall of the Axis did not stop the killing. Many countries had come out of enemy occupation with their political systems wrecked, so chaos replaced oppression. In China, the Communists and Nationalists resumed the civil war that had been interrupted by the Japanese (see “Chinese Civil War”), while Left and Right also fought a civil war over who would inherit Greece. In East Asia, a couple of colonies that had been occupied by the Japanese—French Indochina (see “French Indochina War”) and the Dutch East Indies—seized the moment and rebelled to prevent their former masters from reclaiming control. In Eastern Europe, the nations that had been (liberated? conquered? trampled?) by the Soviet Union tried to set up multiparty democracies, but Soviet-sponsored Communist parties quickly gained the upper hand and put an end to that.

The recently liberated nations had plenty of scores to settle. The Communist partisans (mostly Serbs) who took control of Yugoslavia killed over 100,000 compatriots (mostly Croats) tarnished by association with the wartime fascist government. The French killed 10,000 collaborators after liberation, only about 800 of them after the formality of a trial. The Italians killed from 10,000 to 15,000 war criminals. The Netherlands executed 40 collaborators, while Norway executed 25.

46

The formal trials of high-ranking Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg and other similar trials in occupied West Germany led to 486 executions.

Unlike the Nazis, the Japanese militarists had never centralized power in the hands of one omnipotent dictator. General Tojo Hideki seemed to be near the center of power for most of the war as general, war minister, or prime minister, so he was duly tried and hanged by the Americans, along with six other generals and ministers. Lesser trials led to another 900 or so executions;

47

however, the Americans allowed Emperor Hirohito to keep his throne in order to calm the Japanese resentment of the American occupation.

Tens of thousands of surviving Jews fled Europe to make a new life in the British colony of Palestine, which shortly became the independent state of Israel. The immediate war between Israel and its Arab neighbors in 1947 was the first of many that would continue to erupt, about one per decade, for a long time to come.

Mind-Numbing Numbers

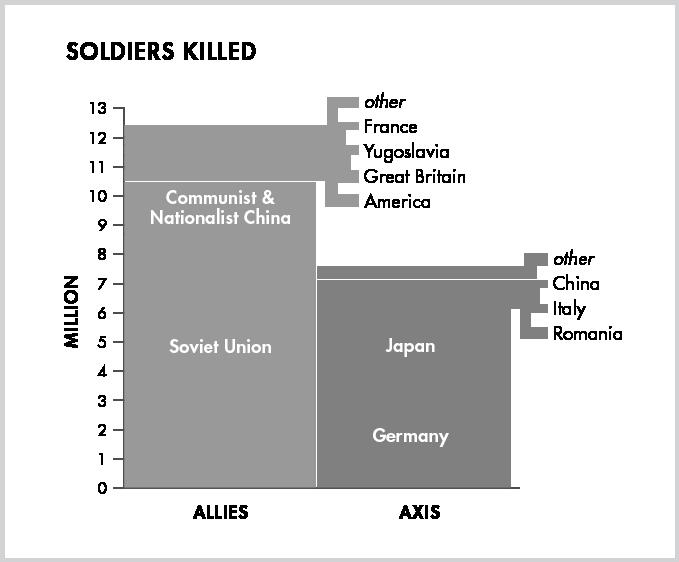

The Second World War killed the most people in history by several different criteria. As a whole, it was the deadliest event in history. It was also history’s deadliest event for many individual nations—Russia, Poland, Japan, Indonesia, and the Netherlands, to name a few—and for several non-national groups of victims—such as soldiers, POWs, and Jews.

The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey claimed that “probably more persons lost their lives by fire at Tokyo in a 6-hour period [March 9–10, 1945] than at any time in the history of man.”

48

This may be true, depending on which numbers you accept, but I’m more inclined to count the 120,000 killed almost instantly at Hiroshima as the most people killed in the shortest time by human agency in history.

*

The killing of 1.1 million at Auschwitz took longer, but it probably counts as the most people killed in the smallest place. The bloodiest battle in history was probably the Siege of Leningrad (if you count both soldiers and civilians) or Stalingrad (if you only count soldiers), but even if they weren’t, then the other likeliest candidates were also fought on the Russian front.

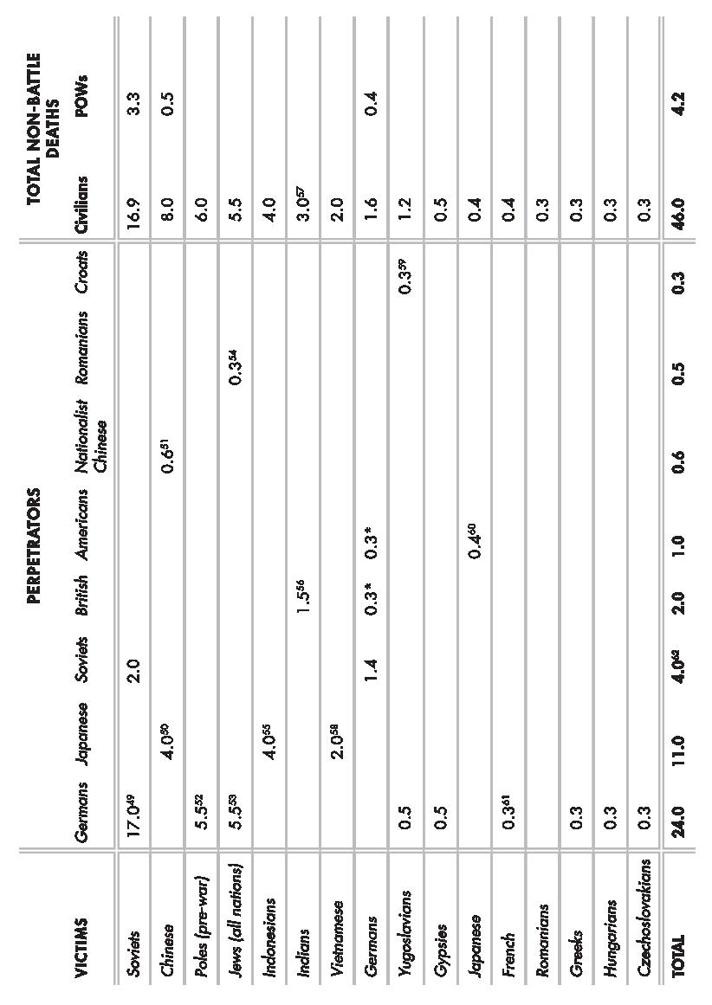

The following chart shows the relative evil and suffering of the participants of World War II by listing how many millions of noncombatants died. The chart shows only death tolls that exceed 250,000 because on the scale of the Second World War, mere tens of thousands was small change. Numbers don’t add up exactly because there’s overlap and a lot of unknowns. The columns under “TOTAL” include everything—murders, negligence, accidents, and innocent bystanders caught in the crossfire—while the columns under “Perpetrators” tally only the deaths that are widely considered to be deliberate, avoidable, or excessive.

Looking at the big body counts isn’t the only way to see how monumentally destructive the war was. You might also want to peek into the little, forgotten corners, and see how many deaths occurred among people that no one ever notices, like New Zealanders.

New Zealand is about as far from anywhere as you can possibly get. It was not under any kind of threat. Even if the Axis Powers had conquered the rest of the world, they probably would have left New Zealand alone, just as they had ignored Sweden and Switzerland. A small country whose contribution to the war hardly tipped the scale, New Zealand could have sat out the war without shifting the balance, but instead the country jumped in and lost 12,000 men in a war it wasn’t required to fight. How many is 12,000? Think of it as sinking eight

Titanic

s.

The war put so many people in deadly situations that unprecedented numbers of people died in surprising and unusual ways. When the British trapped a Japanese force on Ramree Island in Burma, the Japanese tried to flee through impenetrable swamps. It is said that a thousand Japanese went in, but only twenty emerged on the other side. The missing hundreds had been eaten by crocodiles.

The largest shark attack in history occurred when the USS

Indianapolis

was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine. The ship went down too quickly for an adequate distress call to go out, delaying rescue for several days. Of the 900 stranded sailors who bobbed in the water in their life vests, only 316 survived the circling sharks.