The Great Fossil Enigma (46 page)

Read The Great Fossil Enigma Online

Authors: Simon J. Knell

Clarkson and Briggs immediately got down to writing a short account of the discovery for

Nature

titled “The conodont animal is a chordate” and asked Conway Morris and Aldridge for comments. Clarkson and Briggs also had a rather more generous offer to make Aldridge: “Euan and I have had lengthy discussions about a subsequent more detailed paper and, as I told you on the telephone, we would be delighted if you would cooperate as a joint author.” He added, “To avoid any subsequent misunderstanding I should say at the outset that we have decided that the most appropriate authorship would be Briggs, Clarkson and Aldridge, in that order, and we hope that you will be happy with this. It is likely, in any case, that among conodont workers yours will be the name that will spring to mind as author of the conodont animal, once the larger paper has appeared!” The plan was to get the paper written before the summer and submit it to the journal

Palaeontology.

Aldridge was delighted. It had been pure chance that led him to the fossil, but it was the writing of his letter that changed his life so fundamentally. His expertise was indispensible, and if Briggs and Clarkson were not already convinced of this, Conway Morris told them this straight when returning comments on their proposed paper for

Nature:

“Even with my limited experience of conodonts I found the relevant parts of the discussion somewhat simplified; might I suggest that Dick Aldridge joins you in this description rather than waiting for the full blown account later.” When they received Aldridge's “friendly amendments,” their insecurities must have been further amplified, for Aldridge wrote in the arcane code of conodont elements â “Sc,” “Sb,” “Pb,” “M” â and transition series elements. On that same day, Stefan Bengtson in Uppsala, Sweden, where Conway Morris was at the time, wrote a long detailed critique of their proposed paper: “If the conodonts are in situ, which seems likely although not proven, the elusive conodont animal has finally been caught, however badly battered. But is it a chordate?” After a detailed critique of this idea, he wrote, “Obviously, in a poorly preserved fossil one may to a certain extent see what one wants to see. You want to see a chordate, I want to see a chaetognath, and maybe none of us is right. But I find it to be a major weakness of your paper that you herald your fossil as a chordate without giving attention to alternative explanations. (Maybe it is a characteristic of the conodont animal that it leads its investigators to jump to conclusions too quickly. Melton & Scott certainly did so with their zeppelins, I think Simon did so with

Odontogriphus

, I think you are doing so with the present animal â and just now I have to admit that I feel enchanted by the prospect of identifying the same beast as a chaetognath!).” He continued, “I advise you not to stick out your much to[o] valuable heads with assertions on the conodont animal as a filter-feeding chordate.” He then asked them to consider publishing a revised version of the paper in the paleontological journal

Lethaia

, which he edited, rather than

Nature.

“This is clearly a scoop,” he added, “and it could be taken into the next available issue outside the normal waiting list.” Clarkson was then a new associate editor at the journal, and Bengtson also pointed out that

Lethaia

had carried much of the recent debate on conodont biology.

When Clarkson received Bengtson's letter, he was quite taken aback and responded, “I confess that I simply had not thought of the animal as anything but a chordate, because of the apparent myomeres [muscle segments] and the ray-supported structure of the tail. But as you have shown clearly, these do not unequivocally indicate that the animal is a chordate.” He told Bengtson they were still deliberating on whether to publish in

Lethaia

, believing that

Nature

would permit rapid dissemination, but Bengtson told him his journal would not be far behind and would offer a much better vehicle for the discovery. He did the hard sell.

This put Briggs and Clarkson in a difficult position. If they went with the Swedish journal it would mean a full account rather than a piece of breaking news. That would leave virtually nothing for the paper in which Aldridge was to be involved. Briggs asked Aldridge how this might be resolved, but Aldridge simply refused to be part of that discussion. It was for Briggs and Clarkson to decide. He was happy either way, and now also a little bemused because news of the animal had spread like wildfire across Sweden â Lennart Jeppsson had invited Aldridge to speak on the animal at a forthcoming meeting. This put Aldridge in a difficult position. He told Briggs, “I'll have to talk to yourself and Euan about how much or how little you are prepared for me to reveal.” Aldridge was then dissolving rock Clarkson had sent him and despite early doubts managed to find conodonts and clusters. These would help to confirm that this really was the conodont animal. On May 26, 1982, Briggs and Clarkson finally decided to change their plans and invited Aldridge to accompany them in extending their five-thousand-word paper into a full account titled “The conodont animal” to be published in

Lethaia.

They also told Aldridge, recognizing that only he among them had a specialist interest in the animal, “You will be free to write a follow-up in due course. Either or both of us, hope to cooperate on this in any way (compaction of assemblages, stratigraphy, associated faunas) that seems appropriate, but leave this open to discussion.” Aldridge immediately thought about getting a research student working on the topic, but Briggs asked that this be delayed; he was still hopeful that other opportunities might arise from the bed and he and Clarkson did not want to relinquish ownership. Briggs finished, in a manner reminiscent of Scott's advice to Melton, “We look forward to hearing from you about developments but counsel that you keep the specimen reasonably “close to your chest” until our joint paper is out. I guess that discoveries such as this make us all a bit paranoid!”

Clarkson sent the completed manuscript to Bengtson on June 21, 1982. They had kept to their timetable and finished it before the summer, but they had missed the October issue. It would be published in January, after a little tinkering with the finer details, and open the 1983 volume.

3

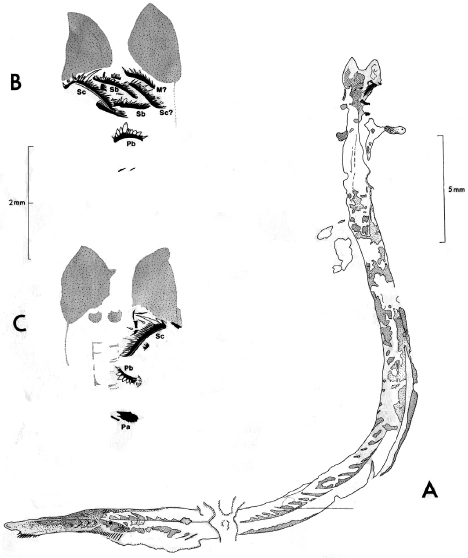

In their description of the animal, the three men did not waste many words on all that had gone before; that was now simply irrelevant. Briggs had decided this early on, and Aldridge agreed. Melton and Scott's beast was unquestionably a conodont eater and Conway Morris's had nothing to do with conodonts at all. The new animal stood alone (

figure 13.1

). It was no surprise that it possessed no skeleton other than the conodont apparatus but a revelation to find that that apparatus was arranged back-to-front. From Schmidt onward, conodont workers had got this wrong. Only Jeppsson and Nicoll had dared to entertain this unorthodox thought. This put the long comb-like elements, two of which held a long, backward-pointing spine-like cusp, near the opening of the mouth. Behind these comb-like elements came the pair of stout blades, and behind these were the platform elements. Among the animal's most intriguing soft tissues was a pair of pale blue ellipses that formed dark lobes projecting toward the front of the body. Between them was a space perhaps leading to the mouth. The body of the animal also showed a line running down the center, evidence of segmentation, a tail fin, and a posterior fin.

In an instant dozens of speculative animals vanished from the minds of those who read the paper, but they were to be replaced by an animal that was frustratingly indefinite. What could it be? Briggs, Clarkson, and Aldridge narrowed the possibilities. There seemed to be just three. The eel-like shape, with possible lateral flattening toward the tail, the asymmetrical posterior and caudal fins, hints of a possible notochord, and indications of segmented muscles all suggested a chordate, but none of these features was so well preserved as to be definite. An alternative was the arrow worm or chaetognath as these animals have eyes positioned where the subcircular bodies appear in the conodont animal, and they possess a similar body shape. But chaetognaths do not have segmented muscles, and this new animal did not seem to possess the arrow worm's paired fins. Neither possibility was certain, and they decided to err on the side of caution.

For now

, the animal would remain in its own exclusive club, the Conodonta. It was still proving resistant. Indeed, it even proved difficult to give it a name. This relied on the identification of the platform elements, but these were poorly exposed. The authors resigned themselves to naming it

Clydagnathus? cf. cavusformis

, meaning it was probably or possibly

Clydagnathus

and like the species

Clydagnathus cavusformis.

13.1.

The conodont animal. This image closely resembles Clarkson's giant camera lucida drawing, 70 cm à 70 cm, of the “lamprey” he sent to Briggs. Clarkson already doubted that it really was a lamprey. The head is top right in (A), with conodont elements indicated in black and repeated structures indicated with stippling; (B) and (C) show the conodont assemblage preserved in the head region and preserved on facing rock surfaces. Reproduced with permission from E. G. Briggs, E. N. K. Clarkson, and R. J. Aldridge,

Lethaia

, 16 (1983).

Concealed within this name is a little poetry, for it was originally the invention of Rhodes, Austin, and Druce. Aldridge had been Austin's student just as Austin (and Druce) had been students of Frank Rhodes. It was Whittington who suggested to Rhodes that he study conodonts. Briggs and Conway Morris, who refereed the paper, had been students of Whittington. That it should be this animal and this name was pure chance, as were Aldridge's involvement and the role of Lagerstätten. But these coincidences are not evidence for scientific ley lines, merely indications of how small the palaeontological community was and how it was organized. One further linkage now developed in the form of Stephen Jay Gould, who had previously admitted that conodonts were rather alien to him, though like all paleontologists he was intrigued by what he called â borrowing from Churchill â this “riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

4

Gould used the discovery of the animal as material for one of his regular articles on fossils in

Natural History

magazine. In it, and claiming Clarkson as a friend â Gould had visited Clarkson on a number of occasions and the two got on well â he used this fossil as a springboard to discuss his “Wonderful Life” view of evolution, documenting the exploits of Briggs, Conway Morris, and Whittington.

Briggs and his collaborators knew that on the most critical points the fossil was more suggestive than conclusive. More material was urgently needed, but a search of other Shrimp Bed collections turned up nothing. So Aldridge assembled a team that included his former research student, Paul Smith, and began a ground assault on the Scottish shoreline. With military force, they applied sledgehammers and crowbars to split the limestone until it would split no more. Acids etched the rock surfaces. But the animal was well and truly holed up. It did not appear. Adopting another line of attack, they tried to dissolve it out, submitting whole blocks of rock to acid immersion. Even this violent interrogation did not bring to light more than the occasional isolated element or cluster. The rock remained silent. There were no more animals.

All looked hopeless, but then things changed, and they did so remarkably. Inspired by a lecture on the animal by Clarkson, Neil Clark, an undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh, visited the site to look for himself. An inveterate fossil hunter with a nose for rarities, on this day â June 16, 1984 â accompanied by fellow collector John Hearty, he was to find the greatest of all rarities: the first in situ conodont animal and the second animal to be found. Hearty gave a “scoop” to

MAPS

, the newsletter of the Mid-America Paleontology Society. “As the sun beat down on us,” Hearty began, as he witnessed Clark find a host of unusual fossils. “Now, by this time you will have realized that Neil was having âone of those days' â he could do nothing wrong!â¦but Neil wasn't quite finished.” It happened toward the end of the day, when his hammer blow laid open the animal. Unfortunately, this one lacked the conodont elements.

5

“Just think of the consequences if this was the only other one found!” Clark later speculated, “No conodont elements in the head region of the animal â the original would have been reinterpreted as chance association.” Luckily it was not the only one. A short while later Hearty collected a block with another animal on it, which he only spotted when he got home. Clark later turned up another on a loose block. Only partially exposed, these animals were then passed to Aldridge and Briggs for further preparation.