The Great Fossil Enigma (54 page)

Read The Great Fossil Enigma Online

Authors: Simon J. Knell

Donoghue was also interested in understanding how these growth processes had changed through the course of the creature's evolution. As to what his data meant, Donoghue permitted his interpretations to be shaped by the “current consensus,” which said that conodonts were chordates. But he took issue with Sansom and colleagues' suggestion that the animal experimented with tissue structure. Instead he argued that dentine itself was so structurally variable there was no need to believe this variety resulted from experimentation. The conodonts' unique white matter remained difficult to interpret, but Donoghue thought it rather more dentine-like than like cellular bone. White matter, it seemed, had its own complex evolutionary pattern; it had not been adopted in the same way, or even at all, across the conodont group as a whole. Clearly it strengthened the element, but it was difficult to say more.

As to the problem of growth, he thought the answer lay not in considering vertebrate teeth â which cannot repair the functional enamel once erupted â but in scales. He noted that in many fish, the scales are drawn back into the dermis for additional growth before re-erupting. Conodont elements were not, then, teeth in the strictest sense, even if they functioned as such. He also postulated that, like the lamprey and hagfish, the conodont animal probably had a skeleton composed of cartilage. As cartilage is rarely preserved in the fossil record, this assertion seemed to him quite reasonable. His interpretation repeated suggestions made by Aldridge and his collaborators back in 1986, but they could not prove them then.

27

Meanwhile, Purnell had been involved in reconstructing the Soom Shale animal's apparatus using the modeling methods Aldridge and his co-workers had exploited in the mid-1980s.

28

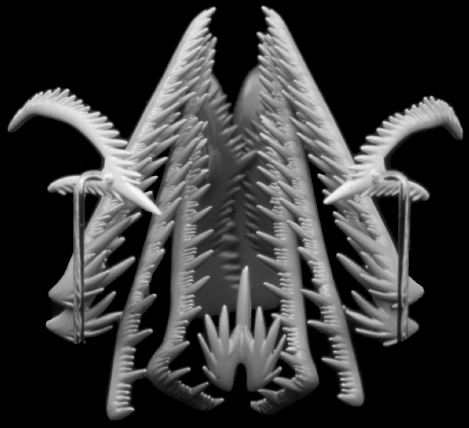

In 1997, along with Donoghue, Purnell presented an operational model of the animal's apparatus. This produced an arrangement of elements suggesting an analogy, in terms of its operation, to the jawless lampreys and hagfish. They imagined a hideous “eversible lingual apparatus,” once held together by muscle and cartilaginous plates.

29

Its spiteful fine-toothed elements were arranged to project outward in a grasping motion, redolent of and perhaps influenced by Ridley Scott's formidable creature in

Alien

(1979) (

figure 14.2

).

30

In 1995, the Leicester and Birmingham groups could celebrate a victory. The Leicester workers en masse did so in an article titled “Conodonts and the first vertebrates” in the popular science journal

Endeavour.

“Some time ago,” they began, “probably during the early part of the Cambrian Period (520 million years ago), a new type of animal appeared. It was small, a few centimeters in length, and elongate; it had no hard skeleton, but a stiffening rod of cartilage along its back and V-shaped blocks of muscle along its sides; it had paired eyes, a brain and tail fins. It was the first vertebrate.”

31

This notion of the ancestral vertebrate was not the conodont animal, for all that it looked very like one. Rather, it was a long-established and widely held concept, stemming originally from drawing a line from amphioxus, which was a vertebrate-like invertebrate, to the hagfish, seen by some as the most primitive living vertebrate. Recent work by British workers had shown that the conodont did not lie on this line but was more advanced â more a vertebrate â than the hagfish. Now the Leicester team explained the significance of the conodont animal and the debate that surrounded it in plain language. The textbook view was that the first vertebrates were suspension feeders living lives comparable to amphioxus and larval lampreys. According to this explanation, they only became predators a hundred million years later. But Purnell considered a predatory condition was necessary for the evolution of eyes, muscles, and skeletons. On this latter point, they too would assert that the vertebrate skeleton began not with defensive armament but with teeth. Although there were still some anatomical uncertainties about the animal, these new vertebrates nevertheless had impact for they had existed for some three hundred million years and had left an unparalleled record of their time on Earth. The article was illustrated with a photograph of conodont elements on a pinhead. One of the most striking images the science had ever produced, it at last permitted the general reader to visualize these obscure fossils in everyday terms. It soon appeared on magazine covers and websites, wherever the science needed to explain itself to a wider public (see this book's frontispiece).

14.2.

Alien jaws. Purnell and Donoghue's reconstruction of the animal's formidable apparatus seen head on. Photo: Mark Purnell, University of Leicester.

Purnell translated this

Endeavour

piece into an article for children called “Armed to the Teeth.”

32

Here, too, the “weird” conodont was a new and exciting clue to that mysterious vertebrate ancestor from which we sprang. “What, I hear you ask, is a conodont? It's a good question, and until a few years ago no-one really knew the answer.” The conodont was made for this dinosaur-loving audience: “One of our early ancestors was a small but very vicious killer!” That killer was illustrated, though it unfortunately lacked

Alien

menace.

In another article, “The conodont controversies,” Aldridge and Purnell disseminated their new vertebrate among evolutionary biologists, most of whom knew little or nothing of the animal. Gee had remarked that modern evolutionary biologists used methods that encouraged a presentist view of the past; they made their decisions based on what was now living rather than on an understanding of the extinct. It was a problem Simpson had recognized back in the 1930s and it had not gone away. But modern biology could not invent the conodont. For one and half centuries the animal had fought for its place among the vertebrates simply by virtue of its tooth-like remains, struggling against doubts that suggested it was simply too old and that its teeth were not as tooth-like as they might superficially seem. As the conodont entered this new world of vertebrate biology, it lost none of its controversy; it appeared from nowhere possessing a rich evolutionary history supported by millions of specimens, and it sought to significantly rewrite history. Of course, Aldridge and Purnell's biggest problem was a lack of certainty about where the conodonts fitted in the vertebrate family tree. But this was true of many of those animals lacking a backbone yet applying for admission to the vertebrate camp. In an attempt to court this new community, Aldridge and Purnell paraded six possibilities for placing the conodont in the tree of vertebrate life. In their

Endeavour

article, they had restricted themselves to one. Of course, a great deal depended on what one might call a vertebrate, but they argued that “authors who have worked on the conodont animal specimens are united in the view that the conodonts belong within the Craniata (= Vertebrata, if the myxinoids are included in vertebrates [)].” They did not point out that these authors belonged to one extended family, but that mattered little. If other scientists were to adopt the conodont, they would do so on their own terms, just as Janvier did. Aldridge and Purnell's paper revealed that there was still much to play for. As Gee noted, “On this evidence, at least, it seems clear that conodonts represent a very early radiation of âjawed' vertebrates, possibly distinct from the radiation of more familiar jawed vertebratesâ¦. In which case, they need not tell us very much about vertebrate origins as such.” But on this, he admitted, the jury was still out.

33

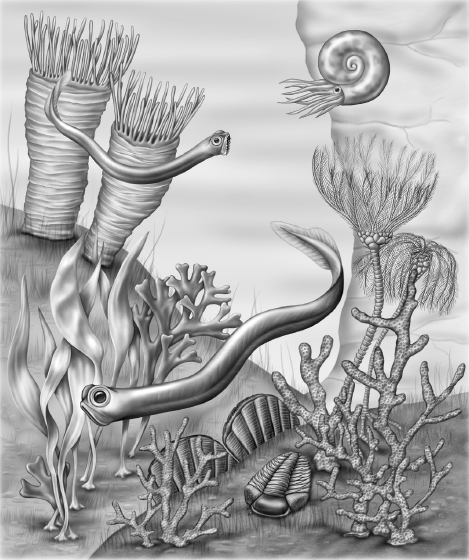

14.3.

The conodont animal as it is imagined today. The animal has been depicted in a range of guises, both comic and factual. In 1993, an image appeared that had the animal possessing huge eyes, an error introduced by a picture editor who flattened a perspective drawing of the animal swimming toward the viewer. This encouraged Forey and Janvier to suggest that the animal might be a larval fish. Nevertheless, the eyes in the Scottish animal were relatively large, which Purnell explained as representing the minimum possible size for functioning vertebrate eyes. The strap-like eye muscles in Gabbott's beast suggested the animal could rotate its eye â a feature only found in vertebrates. Positioned on the front of the head, the eyes also suggested to Purnell that the animal was an active predator. New reconstruction of the animal by scientific illustrator, Debbie Maizels. ©Debbie Maizels/Simon Knell.

These new interpretations were also finding their way into standard textbooks. The author of many, Bristol paleontologist Mike Benton, referred to the conodont as a microvertebrate: “The first fishes date from the Late Cambrian, and the commonest group then, and in the Ordovician, were the conodont animals.”

34

Textbooks produce orthodoxies. Students learn and never forget that first act of learning. The conodont was a vertebrate: established in science, won by campaign, and evangelized across the media.

Of course, the battle was not entirely won, even if it had become the orthodox view. There was still the matter of tree building and negotiating that boundary where life could be said to become “vertebrate.”

35

The territory that had been won for the conodont animal in this campaign continued to be defended and strengthened by those who had fought for it.

36

The new orthodoxy continued to be consolidated. At the conodont's sesquicentennial birthday celebrations in Leicester in 2006, Dick Aldridge suggested it was time to stop beating around the bush and call conodont elements “teeth.” He believed the vertebrate skeleton originated in conodonts and that they were our earliest “stem ancestors.” The concept of stem ancestors here meant the conodonts were the first branch on the bough of an evolutionary tree which had jawed vertebrates at its end.

Among the two hundred or so active conodont workers then on the planet, beliefs varied about what the animal was. Each mind held a slightly different animal. Nearly all believed in the chordate, though some preferred amphioxus as a model.

37

Only a tiny group had taken these thoughts into press. In 2006, the conodont controversies had shifted slightly more to consensus, not least because the mountain on which the conodont had been placed seemed unassailable â its defense was too strong. But as the heat dissipated, those who had built and defended that mountain became drawn into new projects and other animal groups. With Aldridge only a few years from retirement, was the science again to change?