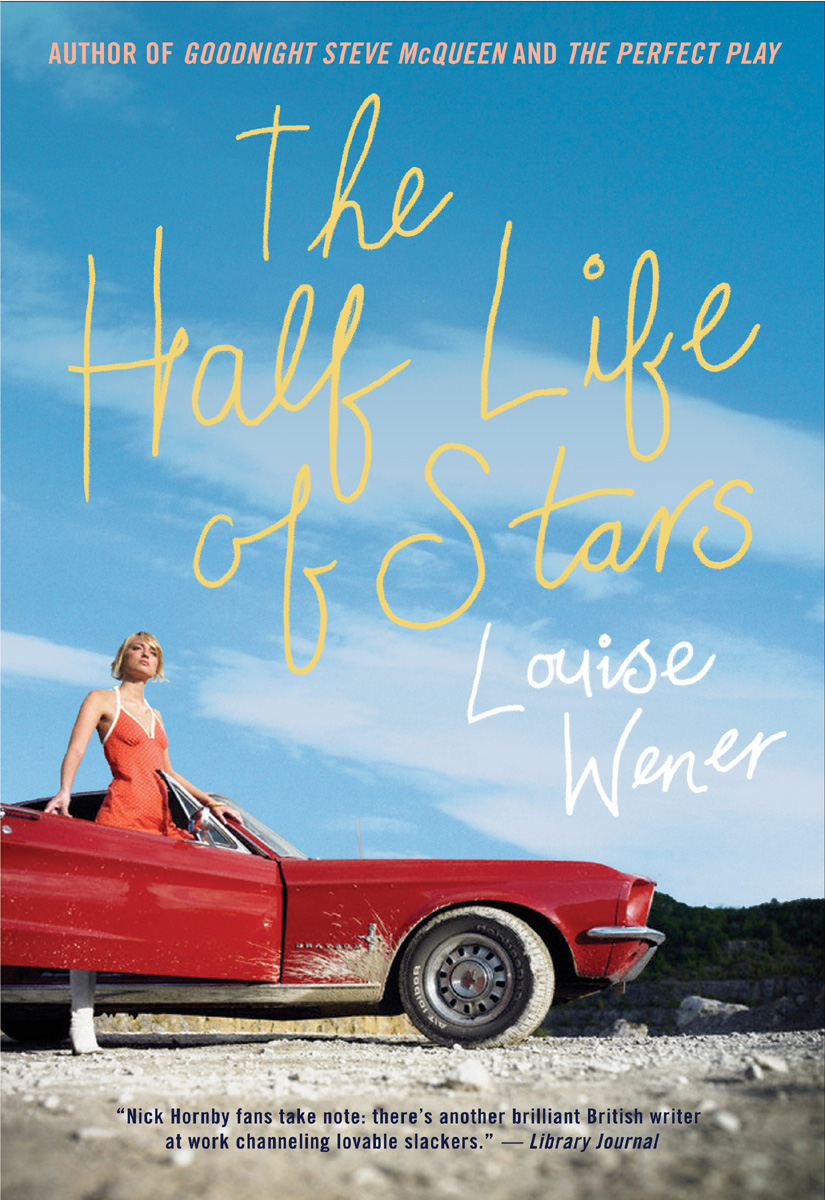

The Half Life of Stars

Read The Half Life of Stars Online

Authors: Louise Wener

A Novel

louise wener

For I.

Our little piece of stardust.

As Daniel yawned and climbed into his father’s car that morning, he saw a poodle being dressed in a red knitted coat. Huffs of hot dog-breath sprang from the animal’s mouth–white, steamy and most likely malodorous–while its owner tightened straps and fastened collars, and swaddled its shivering belly in a layer of cloth. The animal appeared resolutely unimpressed, yelping and digging its paws into the wind-whipped sand while its master tugged patiently at its neck. Even with the benefit of outdoor clothing, it still seemed unwilling to get going.

It was January in Florida and a deep, rare chill had swept the sunshine state from coast to coast. Palm trees swayed uneasily beneath a stiff crust of frost and beaches the length of the Space Coast looked like they’d been newly dusted with sugar. The freeze extended as far south as Miami and the Keys, and the crisp cold air, loaded with the prospect of rain, reminded Daniel of winters back home. In the hours before dawn only the intrepid and the insomniacs and the crazies were out on the streets and Daniel wished–like the dog–that he could have slunk back to the warmth of his bed.

It might not have brought him much comfort. Even safe in their houses, buried beneath their quilts, Floridians were having trouble sleeping. Old men lay awake worrying about their pets. Fruit growers worried about their oranges. Cuban émigrés worried about their relatives making landfall in the sub-zero cold and hoteliers fretted about lost business. And some way to the north, in the depths of a government building, the seven loneliest people in all the world tossed and turned and called out in their sleep, their minds alive with unwelcome nightmares.

As they hit the start of the turnpike, Daniel’s father extinguished his breakfast cigarette. He gave an empty belch like a small cry for help and felt around in the glove compartment for a half-eaten box of Rennies. Lately he’d been guzzling antacids like a newborn baby guzzles milk, and the early start had set off a vigorous bout of indigestion. So profuse were his father’s digestive juices that Daniel sometimes imagined his stomach to be awash with them: gallons of fizzing acid; pools of yellow bile; creeping up the narrow tunnel of his oesophagus until they burnt a hole right through his chest.

‘Excited?’ said his father, stuffing squares of chalk into his mouth. ‘It’s going to be pretty exciting, if it goes.’

Daniel nodded.

‘Long drive again, though. Four hours at least. Should we stop off for pancakes, are you hungry?’

Daniel shook his head.

‘I could eat some dry toast. Maybe we’ll stop for some toast.’

Daniel knew his father wouldn’t stop. The same way he hadn’t stopped the day before. He’d speed without a break all the way to Titusville, then he’d buy them both a hamburger at a drive-through McDonald’s. They’d eat in the car with the radio on while his father muddled himself with directions and map-books, and complained about the illogic of American road signs. They’d been living in Florida for close to a year now, but the exit signs still managed to confuse him.

‘Hey, you awake? We’re almost there.’

Daniel had slept most of the way. He stirred as he felt the car’s engine cut out beneath him and his body snapped easily back to life. These days it took his father a full hour to escape the bounds of sleep, but Daniel was whole in mere seconds. His father examined him carefully, his pride hiding a brief spike of envy. His son the athlete: the daredevil; the championship sprinter. His son the malcontent: the back-talker; the monosyllabic mood machine.

‘How’s your burger?’

‘It’s OK.’

‘Is it good, you like it?’

‘It’s fine.’

‘Your coffee warm? Sometimes they give you a cold coffee.’

‘It’s OK, Dad. Stop asking me.’

Daniel’s father screwed up his serviette and pointed his car eastward towards the Cape. When had his son started drinking coffee? When exactly had he made the switch from Coca-Cola? When had he decided he knew everything about the world when he really knew nothing at all?

‘You think it’s going to go this time? You think that teacher lady’s going to make it all the way up to Mars?’

‘They’re not going to Mars, Dad.’

‘Yeah, I know. Just testing. Just trying to put a smile on your face.’

Daniel turned to stare out of the window, embarrassed by his father’s attempt at humour. How had their relationship deteriorated this far? He’d expected to be an embarrassment to his teenage son–wasn’t that the fate of all fathers–but he hadn’t expected to disgust him. This, then, was the purpose of their trip. Daniel’s mother and sisters had stayed put in Miami Beach while the two of them drove north to repair their bonds. Already, it was turning out badly. This was the second time in two days he’d made the long drive up to Cape Canaveral and he was fighting exhaustion as well as his son’s contempt. Yesterday they’d left Dade County even earlier and stood for hours in the bitter wind with the other sightseers at Jetty Park, while they’d waited for the rocket to go. His son had sneered at him when he’d called it a rocket. But what else was it? It was a rocket that came home again; big deal, it was still a rocket.

They’d called off that first launch just past noon. And for what? Some jammed door bolt that wouldn’t loosen. They’d had to fetch up a portable drill to break it open, but when they’d found one its battery was dead. A billion dollars of the most sophisticated technology known to man, an entire space centre crammed with NASA’s sharpest minds. And still they couldn’t

get the damn thing off the ground: for the want of a lousy pack of Duracell.

But he had to show willing. His son was enamoured by space. When he wasn’t training or running or moping around the house he was combing the universe with his telescope. He wondered what his son was looking for. Black holes? Aliens? Some meaning? What was the point? There was enough to be confused about right here.

Recharged with food and wrapped up in heavy coats they braced themselves for another long wait. The crowd was larger than it had been the day before but the same rumours, whispers and half-baked theories circled the width of the park. It was too cold for the shuttle, too windy; there were icicles hanging from its wings. Daniel’s father rubbed at his eyelids. He hated delays at the best of times and this constant indecision, this permanent state of flux, left him feeling distracted and sleepy. He tried to stay alert through the announcements–it was going, then it wasn’t, then it was again–but he just wished they’d make up their mind. He wondered why people could never do that–take a decision and stick to it. And then, out of nowhere, came the go-ahead. They were positive now, it was certain. The damn fool rocket would go.

By eleven o’clock with the wind dropped to a whisper, the tedium was accelerating to an end. Daniel had a pair of binoculars glued to his eyes and all around him shone the glow of expectation. Children knelt up on their parents’ shoulders, teenagers balanced on the roofs of cars; couples held tight to one another waving flags and freshly painted banners in their hands. Everyone had their radios tuned to the same frequency and the launch commentary spilled out, lubricating the crowd, from a thousand different directions.

At fifteen minutes to lift-off, the air filled with great whoops and cheers and Daniel’s face drenched pink with excitement. Goose bumps spread out like a rash along his arms and he could barely stand still any longer. His father allowed himself a smile. He could drink all the coffee he wanted, be as surly as he liked,

but this boy was little more than a child. As he watched him fidget in those minutes and chew nervously on his lips, he was reminded just how young his son still was. Young enough to judge him: not nearly old enough, yet, to forgive him.

‘Look at it, Dad. Can you see? Here, take these. Take a look.’

Daniel’s father took the binoculars and trained his eyes on the launch pad. Christ, what a bird it was up close. A wild white Moby Dick of a machine, rearing up out of the ground. That gigantic silo that it clung to, framed with rocket boosters fourteen storeys high; each juiced up with five hundred tons of rocket fuel, burning ten tons of the stuff for every second that it flew. What were they thinking of, those crazy astronauts? What was going through their heads, right now? Seven lonely souls locked into a cockpit the size of a saloon car, strapped to the back of the world’s largest firework.

‘How fast is she going to go?’ He said, lowering the binoculars. ‘How fast will she go, after lift-off?’

Daniel squinted at his father, wondering if he might risk the chance to swear.

‘Pretty fucking fast. Close to 2000 miles an hour.’

‘Don’t swear, Daniel, I told you…Jesus

Christ

. Are you sure?’

How could that be? How could that possibly feel? To tear through the earth’s gravitational field, to fly like a bullet and be free. It had crept up on him, this feeling of astonishment, risen up inside of him without him even noticing. His pulse began to race, his chest began to heave and Jesus, what a show. What a

show

. They could see a bed of steam rising up off the launch pad, a billowing cloud of smoky white. It was vapour, Daniel told him. An avalanche of water sluiced out onto the launch site to cushion the violence of the acoustic shock. The sound waves generated by lift-off were so ferocious that they could shake the shuttle apart where it stood.

A thousand radio announcers interrupted them in unison at that point, blared out the same clarion call:

T minus ten seconds and counting–go for main engine start

. The crowd began to count

and Daniel and his father, caught up in the excitement, began to count along with them. So this was it. After two days of waiting and twelve hours of driving back and forth, it really was about to go. All around them hungry faces strained upwards and outwards, away from their own fears and confusions towards the heady recesses of space. What hopes they levied on this fearsome machine, what great expectations it carried. What a thrill it was, just to witness it: to see it break through the boundaries of earth.

They felt the vibrations all at once and together; a faint low groan that rumbled up their bones and spread out like a tremor beneath their feet. Then came the flames, a wildly vivid fluorescent orange glow, that seemed to swallow up the base of the launch pad. And then the monster began to move. It began so carefully, so slowly, like it mightn’t make it at all. They could sense how heavy it was in the air, feel every inch of the effort it was making. And everyone standing with them felt it too, and used their collective influence to will it forward.

‘There she goes, Daniel. Will you look at

that

. Jesus,

look

, there she goes.’

Suddenly she was airborne. Slicing through the sky–as clear now and blue as a Glacier Mint–on a raging catapult of flame. The roar of lift-off thundered towards them, engulfing them where they stood like a living thing. Daniel and his father braced themselves, their troubles all but forgotten. What a vision this was. What optimism linked them at that moment.

It lasted just over a minute, just long enough for a father to relax and exhale and squeeze his son’s shoulder. And was this true? Did he turn and mouth something to him in those final seconds? Don’t worry? I’m sorry? I love you? Daniel wasn’t sure. He couldn’t quite remember. Because somewhere overhead, in the depths of the machinery the edifice was starting to crumble. An aching joint had sighed open, allowing a snap of rocket fuel to break lose. The giant rubber O-ring designed to guard this vital seal was splitting apart like a yell. The sub-zero temperatures had killed it; made it rigid, taut and inflexible. And though

it strained and fought and battled to do its job, it became clear–all too late–that it couldn’t.

‘What the fuck is that? What the

fuck

?’

The bird had stopped dead in its tracks; it simply wasn’t there any more. The skies above the ocean filled with debris and a vast spreading cloud ripped sideways like a storm, in the shape of a scorpion’s tail. They stood in silence for a lifetime. Was it even possible? That this beautiful, brutal machine could all but vanish from the sky?

It was the radio announcer who gathered up their thoughts, who held out a hand to every one of them. In a soothing, respectful voice–one that he had practised at home in front of the mirror in preparation for calamitous occasions–he spoke directly to the nation. It seemed certain that the shuttle had indeed exploded. Recovery boats were in the field. The parachutes they could see unfurling over the ocean were likely to be paramedics, not astronauts. His voice began to slip at that point, crumbling through the speaker like sand. There was a break in the transmission while he took the time to compose himself and new voice–projected from a Tannoy in the park–appealed for the crowd to keep calm.

And what were they thinking, those silent onlookers? Amid the shock and the grief the overriding emotion, Daniel thought, was one of intense betrayal. They had invested in this machine, a part of them had travelled with it. For the brief seconds that it flew they had felt less mortal, less earthbound, less dreary; less bowed by their day-to-day lives. Now the crowd were in free fall; decelerating from hope at an alarming speed, crashing headlong into the grind. It left them feeling dazed and vulnerable. Some began to cry, some began to swear and thump the side of their cars. Most continued to gaze open mouthed at the sky, convinced that if they stared upwards long enough and hard enough, the lost white bird would reappear.

And Daniel stared along with them. He knew those seven astronauts hadn’t made it, but still he couldn’t tear his eyes away.

He felt like he’d be deserting them if he lowered his gaze, that he’d be insulting them the second he turned away. It took a while for him to notice that his father was tugging fiercely at his arm. His face was white with exhaustion, his palms felt gooey with sweat.

‘What a shame,’ he said, breathlessly, as he dragged his son through the crowd. ‘Jesus, what a god-awful shame.’