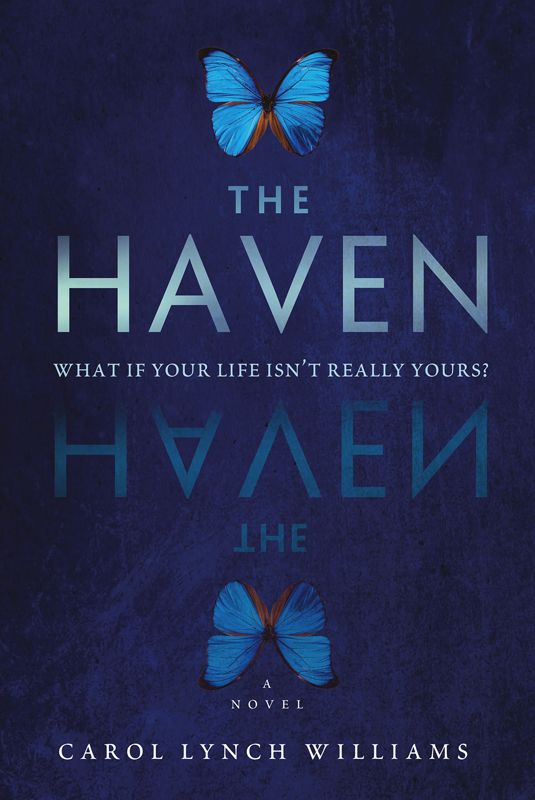

The Haven: A Novel

Read The Haven: A Novel Online

Authors: Carol Lynch Williams

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

To my sixth girl, Cassidy Silversmith

Contents

HAVEN

HOSPITAL&HALLS

Where You Matter

Established 2020

Welcome to:

Blake Green—Faculty

Bonnie Iverson—Faculty

Maria Lopez—Nutritionist

HAVEN

HOSPITAL&HALLS

Where You Matter

Established 2020

Note to all Staff

Please make sure you are present for removals.

1

They came during lunch. They always do. You know, to get one of us.

We bent over our plates of grilled salmon, fresh green beans, and blueberries with cantaloupe. Close enough to whisper. Close enough to touch, if we dared. I could smell the olive oil used to cook the fish. My mouth watered. I couldn’t wait to start eating. In my mind I chowed down this fuel, making my body stronger (I hoped). A better performer (I hoped). Well.

Abigail, someone I’ve known as long as we can both remember, leaned toward me. “It’s like you’re eating with your nose,” she said. “Like some kind of Smell-O-Vision or scratch and sniff.”

“Either works,” I said. Ms. Iverson, who monitors our table, makes sure we eat, and helps Miss Maria set out our Tonics, nodded over her plate like she wanted to eat, too.

A younger Terminal, not yet eight years old, stood.

“About time,” I said in a loud whisper.

“Glorify this food to give us strength,” the male said.

“Glorify this food to give us strength.” We spoke in unison.

“Glorify this food to cure our ills.”

“Glorify this food to cure our ills.”

“Glorify this food to make us Whole.”

“Glorify this food to make us Whole.”

“Glorify this food to make us perfect for the good of our Benefactors.”

“Glorify our Benefactors,” we said, touching our foreheads.

The Terminal sat and the sounds of talking and silverware clinking on china filled the dining room.

I took a bite of the melon we grow here at Haven Hospital & Halls. It tasted sweet like summer sometimes is, though outside a snowstorm headed our way.

It was right after that tiny bite that the side doors to the cafeteria (the ones used only

then

) opened. These doors, almost as tall as the ceiling, and without windows, squeaked out a warning, but it was as if someone had dropped one of the lead crystal vases filled with flowers. The whole lunchroom went dead quiet. Just like that, hushed. I wasn’t sure I could take a complete breath.

“No no no.” My hands went cold, and without saying another word, I clasped them together to keep them from shaking.

In the whole of the cafeteria no one seemed to move. Nothing could be heard, though I wondered if my heart was as loud to others as it sounded to me. Were their hearts beating like mine? Two hundred plus of us in here, add in the Staff and Teachers, and not one noise, just beating hearts, maybe

pounding

hearts. The whole group looking at those gigantic doors opening. The light from an eastern window blinded me and then I could see.

Ms. Iverson stood, scraping her chair on the tiled floor, then sat down like she had made a mistake. Mr. MacGee reached out to her. They aren’t supposed to touch. It’s bad for us to see that. But they did, a brief finger-to-hand contact.

“Good afternoon, Terminals,” Dr. King said as he walked in through the double doors. He strode across the floor, and did that weird thing with his mouth, stretching it up at the corners. His voice was thin, lost in this room full of bodies and plush chairs, a room with tapestries on the walls, flowers everywhere. He waved like he was on parade or something, the sides of his lab coat fluttering because he took such big steps. That sunlight shone on his light-colored hair when he passed beneath it.

Right behind him came Principal Harrison, our pal, everyone’s pal. His ponytail bounced as he walked and his suit was neat, crisp. They hurried to the stage, climbing the stairs two at a time, like maybe they wanted to get this over with.

Did

their

hearts pound?

Just last month I practiced on that stage for the part of Nurse in

Romeo and Juliet,

a play about true sacrifice and giving. It seemed so long ago.

Mr. Tremmel, another teacher, ran for the handheld microphone from the china cabinet drawer.

We watched. Blood coursed through my veins like it wanted to get free. No,

I

wanted to get free. Run. Runrunrun. My feet shuffled.

Time slowed and sped up at the same moment as Dr. King and Principal Harrison stepped center stage, moving faster than any Terminal could. My hands clenched so that my fingernails dug into my palms. What would they say? Who would they call?

Abigail reached for me. Brushed her arm against mine. My head spun with a sudden dizziness and my stomach squeezed in on itself.

I thought,

If I can count to a hundred before they start speaking. Yes, count. Onetwothreefourfivesixseven …

Dr. King and Principal Harrison are Whole—like our Teachers—and they scare me. Hearing the doctor’s name can make my tongue go dry as hot sand.

… twentyonetwentytwotwentythreetwentyfour …

Run! Stay! Count!

My throat went so tight, I thought that bit of lunch might come back up. I could taste cantaloupe again. No longer sweet—now it had the flavor of strong herbs or bad medicine.

… Say each number, don’t skip, don’t skip

… thirtyeightthirtyninefortyfortyonefortytwoforty …

“Not us,” Abigail said. Her voice almost didn’t make it the few inches to me. “Please not anyone I know.” She closed her eyes, then opened them again.

Someone, a little male on the opposite side of the room where all the males sit, let out a cry, and all at once three of the younger Terminals near him wailed out this inhuman sound, mouths and eyes wide open. Dr. King, standing at the front of the room now, tried to quiet them with hushed tones into the microphone. He motioned for their table monitor to help.

… sixtysixtyonesixtytwo …

“We have reports back now for…,” Dr. King said. He held up a manila envelope stuffed with paper and flapped it in the air.

“Stop that fussing,” Principal Harrison said. He pointed in the direction of the wailing males.

… seventyfiveseventysixseventyseven …

Mr. Tremmel leaned over their chairs. I could see him speaking. Two of the males quieted. The third did, too. But his mouth and eyes stayed open—wide. He gripped the table. His hair was blond as the edge of the winter sun.

The whole room felt trapped inside me, along with numbers. My skin felt raw, worried.

I hadn’t done it. Hadn’t counted fast enough. I would leave again or maybe Abigail. Miss Maria leaned in from the kitchen to watch.

“… reports are back for Isaac.”

The mic hummed, and a few Terminals murmured.

Isaac.

It wasn’t me. I wouldn’t go. A headache throbbed behind my temples, then left like it exited my ears.

Rituals,

I had read in

The Terminal Encyclopedia

(and the words were now stuck in my head),

were believed and practiced by some cultures, though this practice ended the American Terminal culture as we know it.

I thought,

My counting ritual worked.

Dr. King stretched his mouth at us again, making his lips into that frightening half moon, then blew into the microphone and continued. “Isaac, after your meal, please go straight to your room. Someone will be waiting for you there. You’ll need your prepared bag, as you know.” He tapped the envelope. “I hope you all have your bags packed and at the ready. Do you?”

We nodded. The whole group of us.

Isaac, tall and red-haired, sat three chairs down from Gideon, who was Romeo in the play. Gideon. My stomach dropped into my lap. What now? First my heart racing, now my stomach lurching when I looked at this male. Definite signs of illness.

Isaac gave Dr. King a nod. Isaac’s lips were pinched—his freckles bright on his now-pale face. A Teacher near him laid a hand on Isaac’s shoulder and he curled forward then shrugged the Teacher away. Isaac stood, shaking his head like he wanted to clear it, and walked for the doors that led from the dining room. The regular doors that would take him to his bedroom. He took one last look at us all.

Isaac was leaving.

I swallowed.

I am not.

He raised his hand in an almost-salute and went into the hall.

He hadn’t even finished eating. The most important part of any Terminal’s day—consuming our nutrients—and he left a full plate behind.

Principal Harrison took the microphone from the doctor and said, “No gloomy faces here. We must keep the rest of you healthy, now, mustn’t we? Eat up. Only the best food, only the best care for you here at Haven Hospital and Halls. Clean your plates. We always recycle, reuse, and never let anything go to waste.”

No one made a sound.

Don’t move, don’t even breathe, and they may not see you,

I thought.

The doctor and our principal left the room, going the way they had come, through the big doors that closed, this time, without a sound. Everyone took on life as minutes crept by. Terminals spoke to each other, soft at first, then the noise level grew.

I didn’t have the strength to pick up my fork. Abigail tapped the back of my hand. My head spun.

“Eat, Shiloh. Abigail,” Ms. Iverson said, from the far end of the table. “Lunch will be over soon. We don’t need you growing weak, too.”

“Yes, Shiloh,” said Abigail. Her forehead wrinkled. She got close enough for our cheeks to touch, though not quite. I slid away. “What would I do if you weren’t with me?”

I blinked to make the dizziness go away.

“Don’t ask that,” I said.

Abigail nodded. “I shouldn’t think of anything outside of Haven Hospital and Halls, but sometimes I do. Like, what I would do if you were gone?” Her voice dropped to a whisper. “I wish we didn’t live here.”

I gulped nothing but air.

“That’s preposterous. We’re Terminals,” I said, drawing out the word. “This is where we live.”

Abigail picked up her fork and pulled a bit of the salmon apart. “If,” she said. “What about

if

we didn’t?”