The Heir of Mistmantle (33 page)

Read The Heir of Mistmantle Online

Authors: M. I. McAllister

Tags: #The Mistmantle Chronicles, #Fantasy, #Adventure, #Childrens

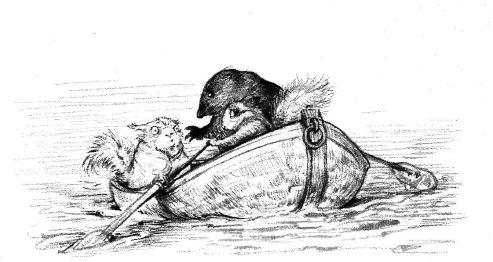

Linty held tightly to the baby as the boat rocked.

The girl’s right. Pity. Let her row. I can push her out if she’s any trouble.

“Go on, then,” she grumbled. “You can take the oars for a bit, just until she settles. Keep that otter back.”

“I’ll send him back when I’m in the boat, I promise,” said Sepia. “But I can’t swim and keep the blanket dry at the same time.”

“He’ll get the oar across his skull if he gets too close,” warned Linty, watching Fingal ferociously.

“When I’m in the boat, Fingal, swim away, fast as you can,” said Sepia quickly, and struggled to keep her balance as she stood up on his wet back and scrambled into Linty’s little boat. She took Linty’s place on the wet rowing bench and reached for the oars, the cold air on her wet limbs sending shivers all the way through her so that her teeth chattered. As the moonlight shone through a gap in the clouds, she saw Linty’s face clearly.

Linty had grown haggard since taking the baby. Her eyes were wild, suspicious, and, to Sepia, quite insane.

Catkin looked well enough, though, as Linty wrapped her in the blanket and cradled her. The baby looked brightly at Sepia—it was a long time since she had seen any face but Linty’s, and this one intrigued her. Sepia smiled, and Catkin smiled delightedly back at her.

“Stop that!” ordered Linty. “Just you row to the mists, girl.”

Sepia rowed as slowly as she could. It was so hard to tell whether it was only fog that drifted past her, or the mists. She hoped it was fog.

Trust the Heart and not the Heartstone.

“Get right away, you otter!” Linty shouted at Fingal. “And that squirrel who says he’s a priest, he has to go. Brother Fir’s the priest, not him. That evil captain must have sent him.”

“The evil captain’s dead, Linty,” said Sepia through chattering teeth. “He can’t hurt you, and he can’t hurt the baby.”

“I said, send that squirrel away!” shrieked Linty. “And row faster!”

“You’ll have to go, Juniper!” called Sepia, and tried to look as if she was rowing faster, though all the time her heart reached out to Juniper and Fingal as they moved away from her.

The mists are at my back and I’ll never see you again…should I grab the baby and swim for it…but she’d kill me and the baby would drown…. Heart help me….

She forced herself to concentrate. She had to stay one step ahead of Linty. She rowed very lightly, knowing that the tide was against them.

“Captain Husk is dead, Mistress Linty,” she said. “Nobody’s allowed to kill babies anymore.”

“Is that right?” asked Linty, but the wary look was still on her face. “You’re lying. I heard them talking about him. He’s back.”

“No,” said Sepia. “They were wrong about that. He really is dead.”

Admire the baby. She’ll like that.

“She’s a very beautiful baby. You’ve taken great care of her.”

“’Course I have,” said Linty, looking proudly into Catkin’s face.

“What’s her name?” asked Sepia.

“Ca…Daisy,” said Linty. “I called her Daisy.”

“And whose baby is she?”

“Why, she’s mine, of course,” snapped Linty. “Whose should she be?” She hugged Catkin tightly. “The king and queen think she’s theirs, but they’re wrong. This is my baby. They didn’t know how to look after their little baby, so they lost her.” She yawned, then said again, “She’s mine. This is my Daisy.”

“I see,” said Sepia, thinking hard, though freezing wet fur made it hard to think at all. “Would you like to take Daisy home to her nest? Her own warm little nest that you’ve made for her?”

“Keep rowing!” said Linty, but she yawned again.

The yawns gave Sepia hope. Nobody could stay awake forever, and Linty must have spent long hours awake, guarding Catkin. As she rowed, she began softly to sing the old Mistmantle lullaby as the boat rocked them….

“Waves of the seas

Wind in the trees

Spring scented breeze…

Linty must be tired. Sepia finished the lullaby and without a break began again, Linty singing it with her. But Linty’s singing gradually became slurred and broken, and Sepia dared to steal a glimpse at her. Her eyes were closing and opening again.

Sepia still sang. Linty drooped, fighting sleep, then jerked up and pulled Catkin more firmly onto her lap, but every time her eyes closed they stayed closed for a little longer. Gradually, still singing, Sepia lifted one oar and rowed with the other, turning the boat round, all the time watching Linty and Catkin.

Catkin was slipping from Linty’s grasp. Should she catch her and risk waking Linty? With a sleepy snarl, Linty scrambled to gather Catkin onto her lap again and settled down to sleep. Sepia still sang, still rowed away from the mists, as Linty opened her eyes a little.

“You’ve got to get through those mists,” she slurred sleepily.

“We are going through them,” said Sepia.

She was watching Linty’s face so intently that she didn’t see the large, rough plank of driftwood bobbing toward them. It didn’t hit the boat hard, but hard enough to shake Linty. Startled and fully awake, she looked about her.

“Where are we going? Why are we…” she stood up in the boat, clutching Catkin as she gazed about. “That’s not the mists, that’s a bit of lifting fog! You’re going the wrong way!”

“No!” said Sepia. “It’s quicker this way, we’re…”

“Don’t you lie to me!” snarled Linty. “Give me those oars! Out of my boat!”

“All right!” said Sepia. “I’ll turn the boat around!”

“Out of my boat!” screamed Linty, and in a swift movement she had put Catkin down and lunged with outstretched claws at Sepia. Sepia seized Catkin. The boat was flung from side to side; Catkin was crying and clinging to Sepia who huddled over her….

“Daisy!” screamed Linty—and she hurled herself again at Sepia with a force that sent all three of them tumbling from the boat as it overturned.

The power of shock and cold took Sepia’s breath away, salt water filled her mouth, as, desperate and suffocating, she kicked her way to the surface. Still clutching the baby, she shook water from her eyes and gasped.

For a strange, wild moment it seemed that the stars were riding or that she was in the sky among them, but as her sight cleared, she realized that she was looking up at them as the wind blew clouds apart. She looked for the boat, but it was upside down and floating away from her.

Then I am dying, thought Sepia, I must be dying, because I can see silver on the sea, a silver path leading all the way to the shore, and there can be no such thing. Then she blinked again and saw that the track of silver was real. It was moonlight, the trail of reflected silver-white moonlight on water, showing her that same plank of driftwood as it floated just in front of her. She struck out for it with her one free paw, clawed her way onto it, and, soaked, shivering uncontrollably, with chattering teeth, yelled for help, though she was still so shocked and frozen that her voice was a feeble thread.

“Juniper! Fingal! Help!” she cried. “Padra, Urchin, Arran, somebody help!”

Above her voice rose the baby’s high wail of distress. She knelt on the driftwood, balancing with one forepaw, clutching Catkin with the other, so chilled that she had to look down to make sure she still held the baby firmly, for her paws could no longer feel anything but the sting of cold.

Oh, Heart help me! When things like this happen to Urchin, the Heart sends riding stars, or the Heartstone…

then she heard an otter’s voice, and the splash of oars.

The Heart heard me. The Heart sent me the otters.

…for the sheer joy of hope she was laughing as she rode the track of moonlight, hugging Catkin and crying out.

“Juniper! Fingal! Over here!” She hugged Catkin tightly. “Don’t cry, sweetheart. We’re nearly home to Mummy.”

“Well done, Sepia.” It was Padra’s voice, calm and reassuring as he and Fingal glided alongside her. With a cry of relief she fell onto his back, sinking one paw into wet fur. Looking over her shoulder, she saw Linty grasping at the driftwood.

“It’s all right now, Mistress Linty,” said Fingal gently. “I’ll take you home.”

Sepia crouched over Padra’s back as they swished forward, fast and sure along the moon track. She didn’t dare look back again for fear of falling, but she heard Fingal shouting, “I’ll need some help here,” and Padra calling for Lugg and Urchin. Then there was the steady ripple of oars and the splash of swimmers. A boat was riding toward them so that the sea rocked more wildly and she bit her lip in fear, but Padra held his course, and she sang the lullaby for the baby and for herself until strong paws were taking Catkin from her; warm, dry paws were lifting her into the boat; and a dry blanket was wrapped around her.

“Well done, you!” It was her brother, Longpaw the messenger, in the light of moon and lanterns. Then Crispin stepped across the boat and hugged her, and suddenly everyone seemed to be hugging her, so that she had to peer past Longpaw and over Crispin’s shoulder to see the one thing she really wanted to see—the sight of Catkin and Cedar hugging tightly and tearfully together on the floor of the rocking boat, as Longpaw took the oars and turned for the shore.

“L…L…Linty,” stammered Sepia. She was still too numb to speak clearly.

“They’ve gone after her,” said Cedar calmly. “Linty will be all right.”

LAGUE AND LICE

LAGUE AND LICE

, I

HATE BOATS

,” said Lugg. “Might as well be in the water as on it. But I wouldn’t have missed seeing Miss Sepia with that baby.”

Urchin shipped the oars and leaned forward. “There she is,” he said.

Tense and shivering, Linty crouched on the driftwood. She stared wide-eyed into the dark.

“Mistress Linty!” called Urchin.

Her head jerked around. “Who’s that?”

“I’m Urchin,” he called back. “Urchin of the Riding Stars. Are you looking for your baby?”

A shudder seemed to convulse Linty from head to tail tip. “You got her?”

“She’s safe,” said Urchin. “We’ll take you to her.”

“I sent that otter away,” warned Linty. She cowered wearily, but she allowed them to row alongside her.

“Give us a paw, then, Mistress,” said Lugg. He heaved the soaked and shivering squirrel into the boat, took off his old blue cloak, and wrapped it tightly round her. “There, now, we’ll get you dry and warmed up. Your baby’s all right now.”

“Where’s the baby?” she demanded, looking all about her.

“We’re taking you to her,” said Urchin. He saw the way she gazed at the top of Lugg’s head where the imprint of a circlet still showed in his smooth black fur.

“You’re a captain,” she said. Her voice was low and accusing.

“Me, Mistress?” said Lugg. “Just a plain old mole, that’s me.”

She continued to stare, and Urchin rowed a little faster. That ring where the circlet had pressed plainly troubled her. Linty did not trust captains. She was deranged enough to have any sort of twisted ideas in her head and to act on them. He rowed harder still. The shore was a long way off. It was a relief to hear Fingal call from somewhere not far away. Help was there if needed. Linty still crouched, her eyes flickering from Urchin to Lugg and back.