The History of Florida (18 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

chiefs to come and receive the king’s gifts. Once in St. Augustine, the native

leaders negotiated al iances of trade and mutual defense and registered a

request for friars. In Spanish eyes, these acts made them and their vassals

subjects of the king of Spain and neophyte Christians.

Churches and convents rose in

cabecera

towns, giving paramount chiefs

access to exotic goods, influential allies, and new forms of spiritual power.

From these mission centers, or

doctrinas

, missionaries cal ed

doctrineros

serviced strings of outstations, or

visitas

, in towns of lesser importance. To

maintain the “divine cult” in all these places, Franciscans relied on the sons

of caciques, whom they trained to be sacristans, musicians, interpreters,

catechists, and overseers, and on orphans, whom they raised to be garden-

proof

ers, grooms, and cooks.

The Florida situado underwrote the doctrinas much as it did the presidio.

In St. Augustine’s 300-man garrison, missionaries and soldiers were budget-

arily interchangeable, costing the Crown 115 ducats a year apiece, and, until

the number of

religiosos

on the rol s was capped at forty-three, every added

friar meant one fewer soldier. Out of deference to a Franciscan’s vow of

poverty, his stipend was issued in the form of supplies, cal ed “alms from the

king.” From other royal funds the friar received a vestment allowance called

“habit and sandals” and, if he was an ordained priest, an altar allowance of

wine, wheat, and wax. New churches, too, were subsidized. When a town

achieved the status of a doctrina, the Crown made it a 1,000-peso baptismal

gift of religious essentials: vestments, linens, images, vessels, parish regis-

ters, bel s, and an altar stone. The natives prized this sacred treasure and

sought to keep it whether or not they had a priest in residence to conduct

services.

From 1587 through the 1620s, Spanish efforts created a tier of mission

provinces along Florida’s east coast and up the north-flowing St. Johns River,

with its two districts of Mocamo (Saltwater) and Agua Dulce (Freshwater).

Republic of Spaniards, Republic of Indians · 81

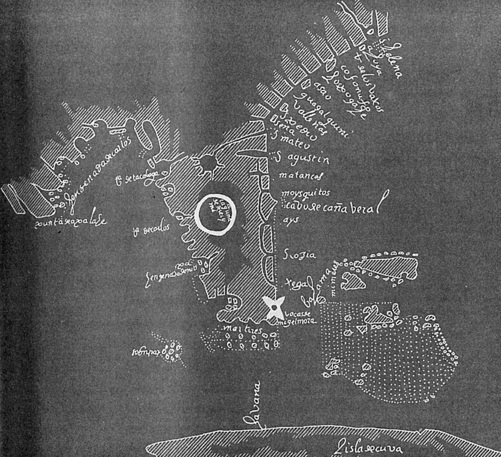

Mapa del Pueblo, Fuerte y Caño de San Agustín. . . . A bird’s-eye view of St. Augustine

proof

and surrounding area drawn by an unknown cartographer, probably in 1593, shows

the principal structures of the town, with vertical board walls and thatched roofs and a

wharf extending into the Matanzas River (

left

); the town’s seventh wooden fort (

right

);

and the Indian mission and town of Nombre de Dios (

upper right

).

This first wave of expansion, the Nearer Pacifications, added an element of

Indian tribute and labor to the support system.

The Timucuan chiefs near the presidio were the first to prove their loyalty.

During the sixteenth-century wars, don Gaspar Marquez of the town of San

Sebastián provided the Spaniards with scouts, porters, couriers, boatmen,

and archers. When St. Augustine was temporarily overrun by castaways

from the wrecks of five galleons, doña María Meléndez, cacica of Nombre

de Dios and wife of a soldier, came to the rescue. The Crown rewarded her

timely gift of provisions with 500 ducats worth of red cloth. By the turn of

the century, Governor Gonzalo Méndez Canzo was drafting natives from

Guale province in present-day Georgia to rebuild St. Augustine, which had

been destroyed by fire and a flood. The laborers received a ration of maize

and a daily wage in trade goods. Thereafter, unmarried Indian males came

82 · Amy Turner Bushnel

in relays from the provinces to cultivate the soldiers’ fields, or

sabanas

, in a

labor levy that historians call the

repartimiento

.

Spaniards also made themselves beneficiaries of the Sabana System,

which was the native method of public finance. By custom, each planting

season the commoners of an Indian town planted one sabana of maize for

each of their caciques or cacicas and another for the community as a whole.

Now, with their new iron adzes and hoes, they cleared and planted other

sabanas for the “service of the convent” and the “service of the king.” Nor

was this their only contribution: often they were pressured to sell the sur-

plus of their harvest to the presidio on credit, in what amounted to a forced

loan. The colony became increasingly dependent on these transfers of labor

and produce, sanctioned and brokered by the Hispanized chiefs. As a re-

ward for their services, the rulers of the Republic of Indians were honored

with ceremonial staves of office, entertained by the governor, and given gifts

of European garments and weapons for themselves and of cloth, blankets,

tools, and beads for their followers. The expense of “regaling” the Indians

was the one open-ended fund in the situado.

A nation conquered by the gospel instead of the sword was not supposed

to be subject to the labor levy, but all of the Florida pacifications seemed to

turn into conquests. Years of Spanish steel, firepower, and scorched-earth

proof

campaigns were required to divide and conquer the natives of the East

Coast, and each chiefdom that rebelled against Spain’s overlordship was re-

conquered and reintegrated under new terms. Meanwhile, undaunted by

the Spanish presence, French corsairs continued to trade with the natives for

ambergris, a perfume fixative, and sassafras and china root, popular specif-

ics for syphilis. The regions they favored were Ais, above Cape Canaveral,

and Guale, on the coast of present-day Georgia. In 1596, the Spaniards took

action by treaty, turning both Ais and Guale into provinces.

The Guale Uprising of 1597, the best-known of the Florida revolts, began

with the kil ing of five friars. The war lasted for six years, during which

French corsairs came and went freely in Guale ports. At last, Governor Mé-

ndez Canzo defeated the rebel leader Juanillo and sentenced the people of

his town, Tolomato, to service a portage near the capital. The province of

Ais also rebelled in 1597, with more immediate consequences. A raid on the

border town of Surruque yielded fifty captives, whom the governor con-

demned to terms of slavery and distributed among his men. Set free by royal

order, the Surruques were relocated where they, too, could make themselves

useful to the presidio, but unlike Guale, Ais did not return to the fold. The

Eastern Timucuans did their share of rebelling. In 1629, in a spontaneous

Republic of Spaniards, Republic of Indians · 83

proof

Mapa de la Florida y Laguna de Maymi. . . . (Map of Florida and of the lake of Maymi

[Okeechobee]) drawn by an unknown Spanish cartographer during the period 1595–

1600, depicts a somewhat squared-off peninsula with a misplaced Okeechobee. It is

valuable for its list of place-names, from Santa Elena in the northeast around to Punta

de Apalache in the west.

uprising at the ferry town of San Juan del Puerto, a cacica and her vassals

freed her brother from soldiers who were taking him, bound, to St. Augus-

tine. Governor Luis de Rojas y Borja sentenced the cacica to be hanged and

her confederates to exile and hard labor in Havana, with their ears docked.

War and disease worked in tandem to empty the eastern doctrinas. Be-

tween 1613 and 1617, half of the 16,000 converted Indians in Florida and an

unknown number of other natives died of a “plague,” and other epidemics

followed. The colony was further beset by hurricanes and pirates. The great

storm of 1622 was responsible for the loss of many ships between the Keys

and Bermuda. For years afterward, salvagers from St. Augustine haunted

the wreck sites, while Dutch and English corsairs lurked near Cape Ca-

naveral to chase their vessels onto the shoals. More than one supply ship

84 · Amy Turner Bushnel

trying to escape these enemies ran aground on the St. Augustine sandbar.

Coastal Indians traded with the interlopers as they came ashore for wood

and water. No help came from the Crown. Instead, the presidio found its re-

inforcements and matériel diverted to other garrisons. The situado fell years

behind. It was a time of short rations and missing wages. The low point was

reached in 1628, when the corsair Piet Heyn captured the Fleet of the Indies

off the coast of Cuba, with the subsidies for all of the Caribbean, including

Florida, on board. Nor did a peace treaty in Europe end hostilities in the

Americas, where hundreds of unemployed soldiers and seamen turned to

piracy.

Harassed by seaborne enemies and with dwindling resources in capi-

tal and labor, the colonists turned their energies inland. Franciscans made

dramatic expeditions into new territory, with banners flying and escorts of

Indian arquebusiers. There was even a resurgence of interest in Menéndez’s

Greater Florida. Governor Rojas y Borja alone sent three parties of Indians

and soldiers to investigate the stories of gold mines, diamonds, and freshwa-

ter pearls told by veterans of the Juan Pardo expeditions. Two parties turned

back; the third reached fabled Cofitachequi, looted by Soto more than eighty

years earlier. But the Crown refused to countenance a conquest that would

push the northern boundary high into the Appalachian Mountains.

proof

The impulse for the second wave of expansion—the Farther Pacifications,

lasting from the 1630s to around 1670—was not a royal initiative but came

from within the colony. In the Gulf, floridanos scented opportunities for

private trade as well as fresh sources of provisions and labor. Their first step

was to “pacify” the Pohoy, Tocobaga, and Calusa who had long dominated

the peninsula’s Gulf Coast and rivers. Captain Juan Rodríguez de Cartaya

made the western watershed safe for Christianity with a gunboat, and the

result was the new mission province of Timucua, of which the northern part

was sometimes called Timucua Alta, or Yustaga.

In 1633, at long last, Governor Luis de Horruytiner was ready to let the

Franciscans carry the Evangel into fertile and populous Apalache, in the

Red Hil s surrounding present-day Tal ahassee. That province’s port, he as-

sured the Council of the Indies, would provide the Fleet with a haven from

storms and corsairs, serve as a supply depot for the western missions, and

guarantee the food supply for St. Augustine’s 500 inhabitants. Boatloads of

maize would leave the Apalache port of San Marcos and follow the curving

coast to the Timucuan port on the San Martín River (combining the Suwan-

nee and the Santa Fe), where the maize could be transferred to pack animals

and taken overland to the capital. Something the governor did not mention

Republic of Spaniards, Republic of Indians · 85

was the rapidly growing city of Havana, a short week’s sail from the fields of

Apalache.

The populous new provinces replenished the number of peasant farm-

ers and repartimiento laborers in Florida. At the same time, the new ports

on Gulf rivers offered outlets for a flourishing coastal trade with Havana in

cured deerskins, dried maize and beans, chickens, hogs, and ranch prod-

ucts and drew Caribbean buccaneers into Gulf waters. That the traffic with