The History of Florida (42 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

mediate extinction, although the effects of depopulation due both to intro-

duced disease and direct conflict with the Europeans and the movement of

towns did much to unsettle the traditional social structure. However, with

the arrival of British colonists, first on the Carolina coast and, by 1670, in

Georgia, the Creeks, by virtue of their location, assumed a pivotal position

in the trade networks opening up on the emerging colonial frontier. Deer-

skins, in great demand in Europe for making clothing, saddles, and other

items, passed from Indian hands to traders located at posts on the fal line or

on the coasts, while the Indians reaped iron tools and utensils, beads, coarse

“stroud” cloth, and guns and ammunition in the exchange. The Creeks were

quickly and deeply enmeshed in an expanding commercial economy. Mean-

while, in Florida, things had not gone well with the native tribes. The more

proof

populous groups—the Calusa of the southwest coast, the Timucua-speaking

peoples of the central interior, the Apalachee of the Panhandle—had borne

the brunt of the first encounters with the Spanish conquistadores beginning

early in the sixteenth century. Fol owing the establishment of St. Augus-

tine in 1565 by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, the serious missionizing of the

Florida Indians began. After a failed Jesuit effort, Franciscan priests concen-

trated on the conversion of the surviving Timucua and Apalachee Indians of

north Florida. Besides the earnest desire on the part of the mission priests

to bring Catholicism to the natives, the Spanish colonial government in St.

Augustine looked upon the mission chain to provide a first line of defense

should the British decide to expand southward. When the inevitable push

did come, the smal , isolated mission settlements, most of which were not

garrisoned, could not hold. First in the 1680s, and then more seriously be-

tween 1702 and 1706, the Florida missions were assaulted by wel -armed,

British-backed Yamasees and Creeks, who swept some 1,000 Florida Indians

into plantation slavery on the rice coast of Carolina.

Despite the apparent good feeling between the British and the Creeks, in

1715 “Emperor” Brim of the Coweta Creeks attempted to organize a unified

strike against the British, French, and Spanish colonists in former Indian

198 · Brent R. Weisman

proof

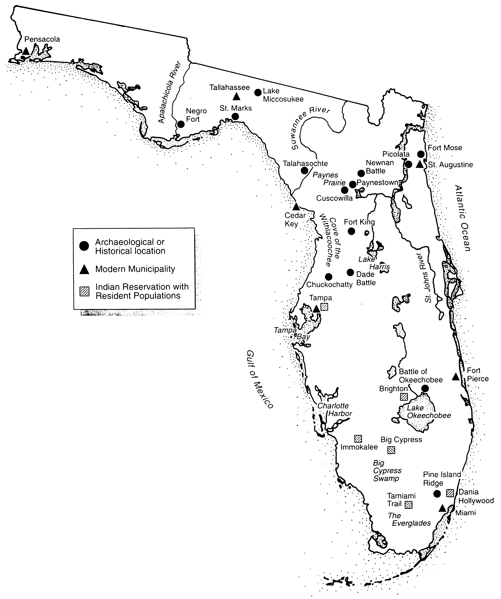

Map showing locations mentioned in the text.

territory. When the first attack of the so-called Yamasee War failed, some

of the Creek towns moved from their former locations to avoid retaliation,

while these and other towns in the Lower Creek region of central Georgia

began a cautious realignment toward the Spanish in Florida. Taking advan-

tage of this turn in allegiance, in 1716, 1717, and 1718 the Spanish sent Diego

Pena among the Lower Creeks in an attempt to entice them to move to the

largely vacant Florida peninsula. A number of towns—Oconee, Yuchi, Sa-

wokli, Apalachicola—responded favorably to Pena’s offer, and the gradual

native repopulation of Florida was begun. Slowly, in the middle decades of

Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee Peoples · 199

the eighteenth century, the old Apalachee area around present-day Tal ahas-

see, the Apalachicola drainage, the central Florida region surrounding the

great Alachua Savanna (Paynes Prairie), and, to a lesser extent, the rolling

uplands northeast of Tampa Bay, witnessed the transformation of Creek

into Seminole. With these peoples came languages new to the Florida pen-

insula. Hitchiti, ancestral to the Mikasuki language spoken by members of

the contemporary Seminole and Miccosukee tribes, could be heard in the

Alachua Savanna, Apalachicola, and Tal ahassee areas. Muskogee, or Creek,

today spoken on the Brighton Seminole reservation, was also to be heard in

some of the Tal ahassee towns and in the settlements above Tampa Bay.

Early Seminole history can be divided into two periods: Colonization

(1716–1767), the initial migrations of the Creek towns into Florida; and En-

terprise (1767–1821), the era of prosperity under British and Spanish rule of

Florida prior to the American presence.

Colonization (1716–1767)

The exact dates for the settlement of Florida by the Creeks are not certain,

nor are they likely to be, given the uneven documentation of the time. It

does not appear, however, that these first Florida towns virtual y replicated

proof

in architecture and social structure the Creek settlements to the north.

Squareground towns, notably at Latchua or Latchaway (on the rim of today’s

Paynes Prairie) and on the west bank of the Suwannee River in the vicinity

of Old Town (Dixie County) continued to be the hub of social and political

life. A squareground typical y consisted of four open pavilions at each side

of the square, one of them special y designated for the chief like Cowkeeper

of Latchaway and White King of the Suwannee town. In the central plaza of

the square was the dance circle. Red towns still battled White towns in the

bal game, as they had in Creek country, the peace pipe or calumet ceremony

still opened important proceedings, and the black drink (actual y known to

the Indians as the “white drink”) still purified both mind and spirit.

Although there was a basic continuity of the Creek culture pattern, there

was an increasing and purposeful separation by the Florida Indians from

the political affairs of their Creek counterparts to the north. In 1765, when

Governor James Grant of the British colonial government called the Creek

leaders together for the Picolata Congress, at which he hoped to gain from

them boundary concessions to land east of the St. Johns River, the shrewd

Cowkeeper was not in attendance, preferring to pay the governor a per-

sonal visit a month later. By Cowkeeper’s own testimony, he had little formal

200 · Brent R. Weisman

contact with the Creek leadership during the decade previous. Cowkeeper’s

case also il ustrates how difficult it is to characterize any aspect of Seminole

history with simple generality, for while he led his band of Oconees to settle

in Spanish Florida, he boasted of killing eighty-six Spaniards and hoped to

do away with more. Yet he seemed to have little use for the British in Florida

(although he was regarded as friendly), and little direct interest in Anglo-

Creek politics. Perhaps his strongest inclination was in maintaining a degree

of autonomy for his people. At St. Marks in the former Apalachee territory,

the Spanish established a trading post in 1745, hoping to lure neighboring

Lower Creeks into permanent settlement. For a time this was successful,

with the founding of Creek towns in the area under the overall leadership

of Secoffee, the son of Brim. However, the Spanish had difficulty provision-

ing the store to meet demand as the quantity of deerskins brought in far

surpassed their expectation. Indian restlessness grew in this part of Spanish

Florida.

The archaeological remains, what few there are that can be confidently

dated to the colonization period, show a strong continuity of Creek material

culture. Pottery vessels, the best collection of which is from the Suwannee

River, are of the same form and function as similarly dated Creek vessels,

and bear the same “brushed” surface treatment and styles of rim decora-

proof

tion. Trade goods found, such as razors, knives, gun parts, glass beads, silver

cones and earrings, buckles, and horse tack indicate full participation in the

trade economy.

As the native involvement in trade intensified, and as tensions between

Indian, Anglo, French, and Spanish on the colonial frontier continued to

mount, the underpinnings of traditional Creek society began, slowly at first,

to give way. The power of hereditary leadership began to diminish as trad-

ers plied the interior looking to make deals with whomever they could. As

social y sanctioned warfare became an unacceptable means for young men

to gain their manhood because of the turbulence and disruption it caused

for the colonists, gangs of mounted warriors roamed the frontier looking

for opportunities to test their bravery and courage. Such was the temper of

Indian Florida when the British gained control in 1763 in accordance with

the terms of the Treaty of Paris. By the end of British rule twenty-one years

later, it could be said that there were no longer any Creeks in Florida, only

Seminoles.

Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee Peoples · 201

The Period of Enterprise (1767–1817)

Despite their overall administrative prowess, the British in Florida seemed

ill-prepared to deal with increasingly complex question of Indian trade and

land rights. Through a series of conferences with the Creeks set to clarify

these concerns, at Augusta in 1763, St. Marks in 1764, and Picolata in 1765,

John Stuart, Indian agent for the Southern District, became aware of in-

creasing Indian dissatisfaction and demands relating to trade and of the

emerging separateness of the Seminole from Creek. Specific treaty nego-

tiations also imply that there was separateness, perhaps even antagonism,

between the Alachua and St. Marks settlements. Although the beginning

date for the period of enterprise could be set at 1763, when Great Britain

took possession of Florida, by 1767 Anglo-Indian relations were relatively

stable and the term “Seminole” or some derivative thereof was coming into

common use. In between the lines, to judge from Stuart’s letters of 1767, this

term was used to designate those natives of Creek origin living beyond the

control and reach of the Creek Confederacy and was understood to mean

“wild people” more than “runaway.”

This was a time of tremendous radiation of the Seminoles across the Flor-

ida landscape and, of course, a great increase in their numbers. In addition

proof

to the Cowkeeper’s Alachua Seminoles, now settled at Cuscowil a, major

towns were found at Talahasochte on the Suwannee River, on the St. Johns

River near present-day Palatka, and Chukochatty near present-day Brooks-

ville. By 1774, nine substantial towns, most, if not al , with squaregrounds,

were present in the Florida; by 1821, this number had increased fourfold. In

the old Apalachee area, major vil ages were located at Mickasuki (also cal ed

Newtown), and Tal ahassee.

The impetus for this Seminole expansion was trade. Using fire drives and

firearms obtained by trade of direct gift, Indian hunters took large numbers

of deer for the skin trade, ranging far south to the Everglades. For 18 pounds

of skins a hunter could obtain a new gun; for 60 pounds (a not unrealistic

take in a good year) a new saddle could be had. The British “one trader–one

town” policy, designed to prevent competitive traders from unduly promot-

ing vil age factionalism, had the unintended effect of stimulating the forma-

tion of new towns. Not all the Seminoles supplied to the traders came from

the forest. Particularly in the fertile uplands east and northeast of Tampa

Bay, plantation agriculture developed. Corn, rice, watermelons, peaches,

potatoes, and pumpkins grown in plantation fields were taken to St. Augus-

tine to provision the perpetual y needy citizens of that city.

202 · Brent R. Weisman

Using large, seaworthy canoes, Seminoles from the Suwannee towns and

from a town at the head of today’s Charlotte Harbor traveled to Spanish

Cuba to trade in the hope of getting better prices than those offered by the

British. However, when Spain again took possession of Florida in 1783 fol-

lowing the American Revolution, trading houses established under British

rule were encouraged to remain by Governor Zespedes to ensure conti-

nuity in trade relations. The leader of the Creek Confederacy, Alexander

McGillivray, attempted to promote peaceful conditions among the Creeks

and Seminoles and the Spanish by nurturing the Indian trading company

of Panton and Leslie, while fending off increasing pressure from the en-

croaching Americans. But peace in Spanish Florida was not to be. Tensions

mounted between the Florida Seminoles and the new American residents

of Georgia, and armed conflict, to be detailed in the next section, erupted